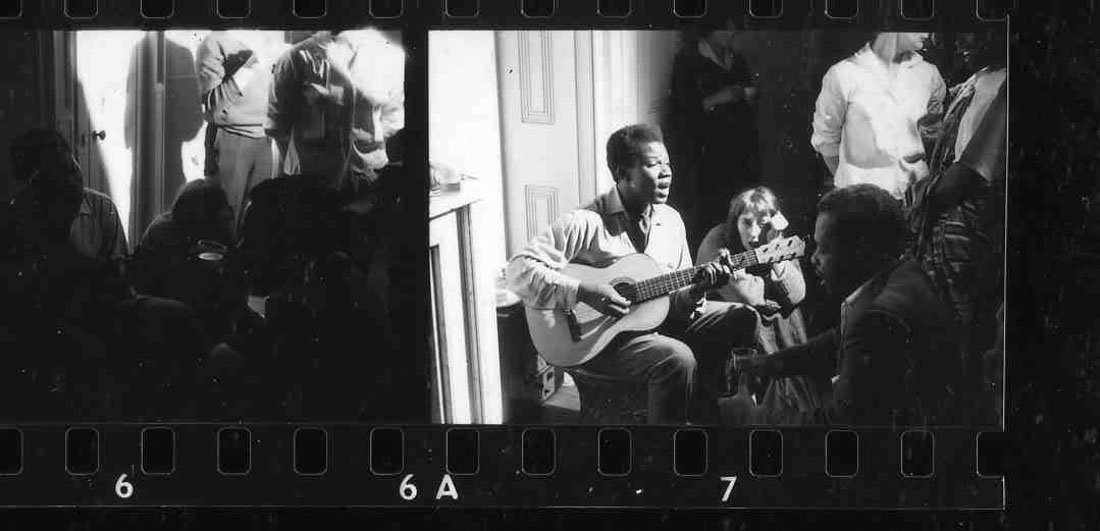

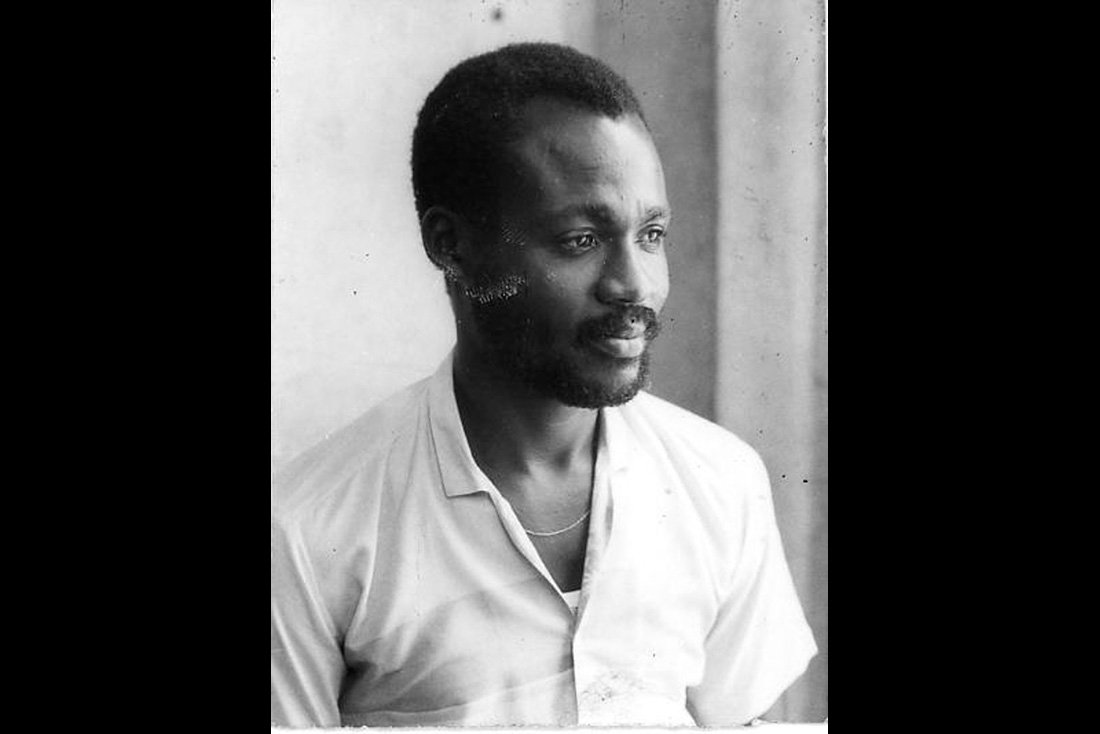

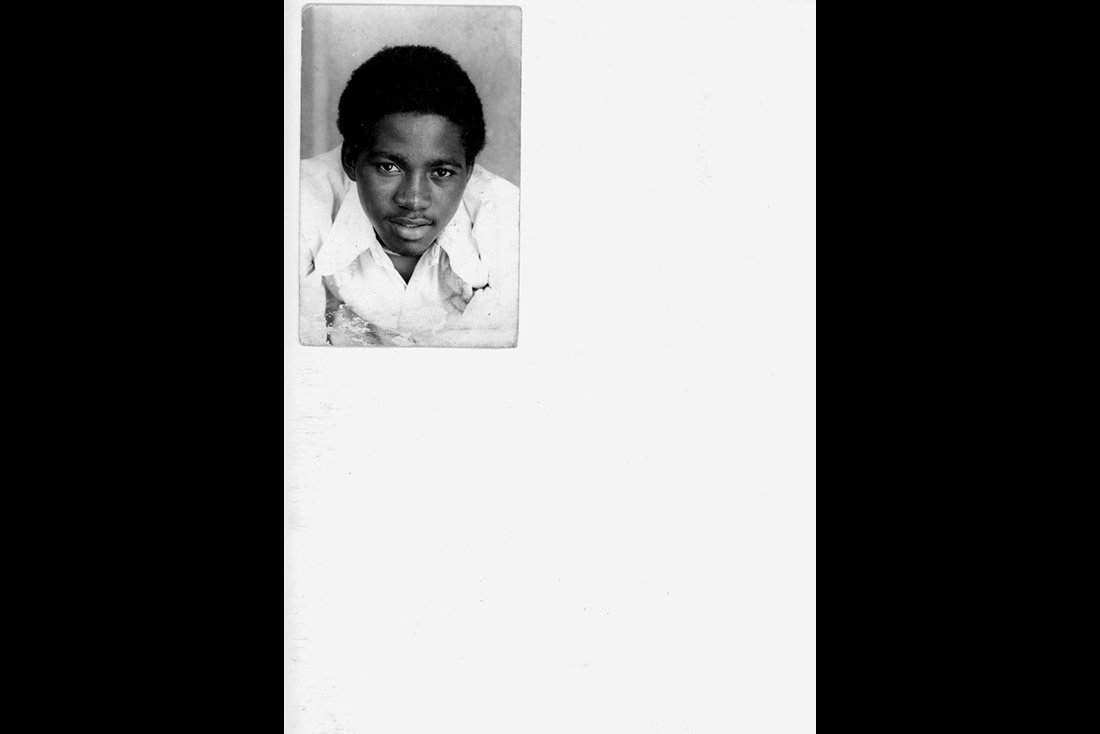

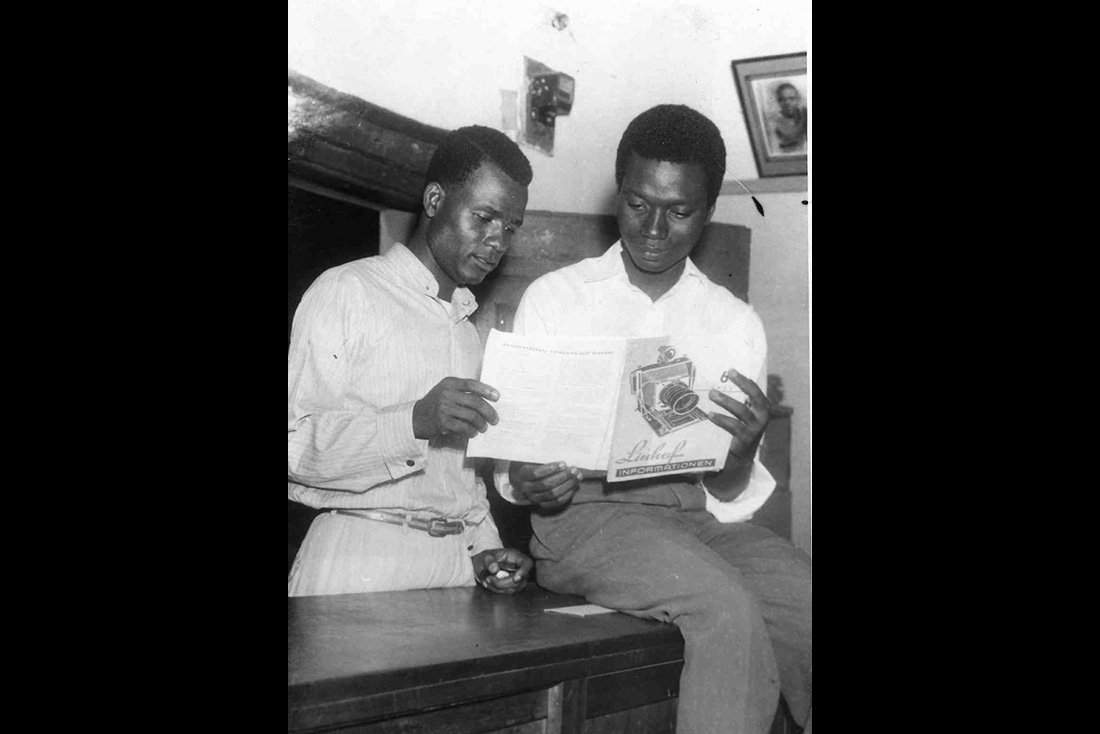

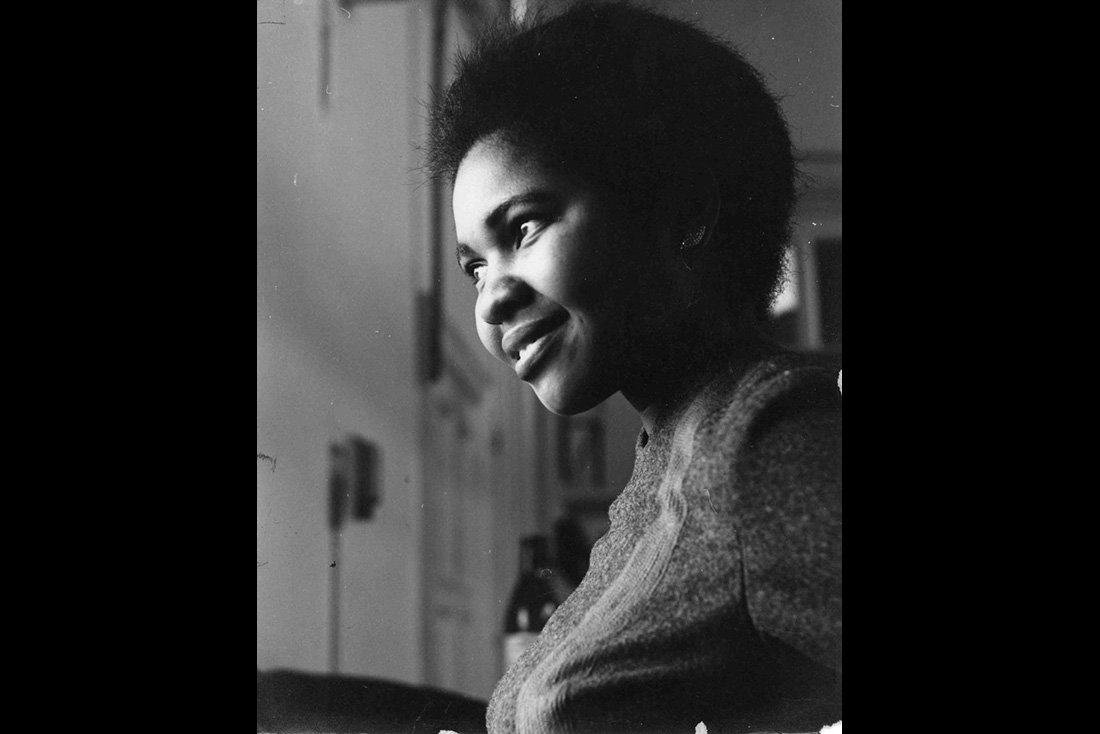

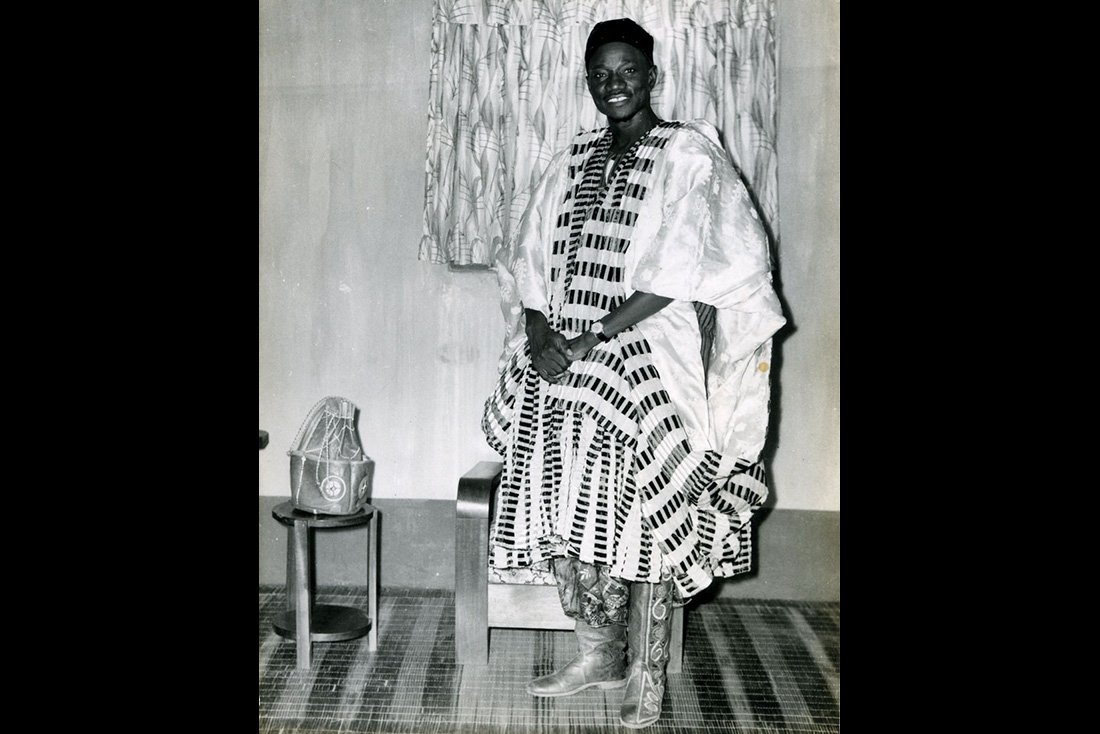

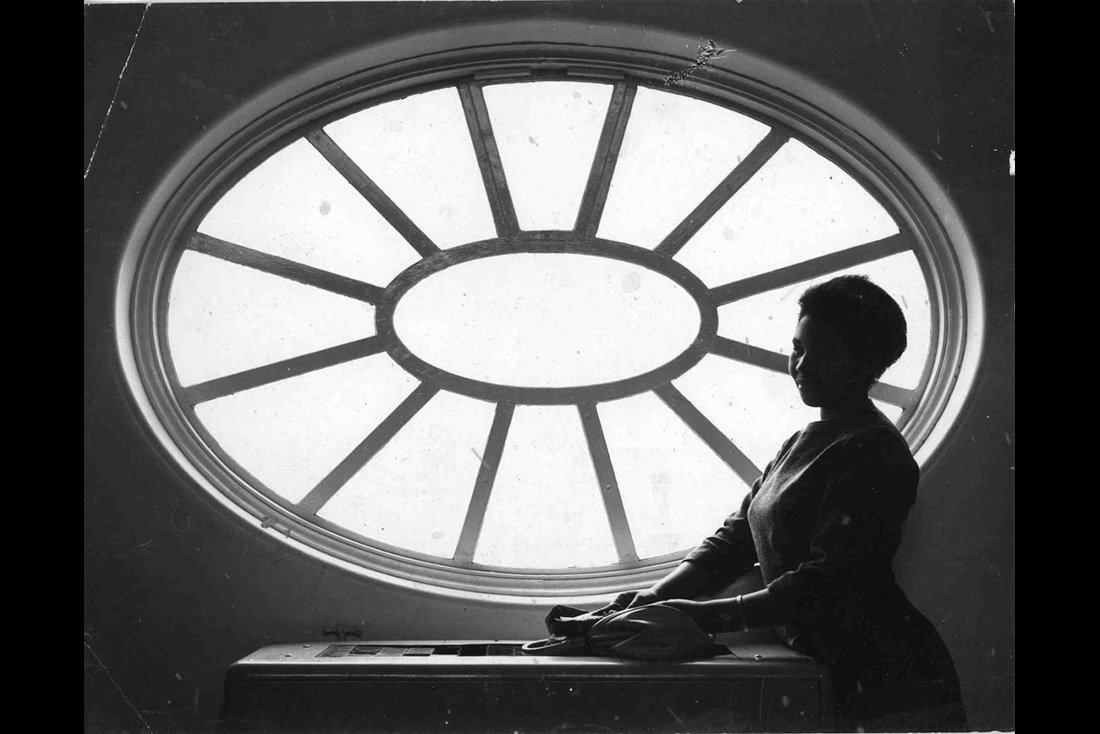

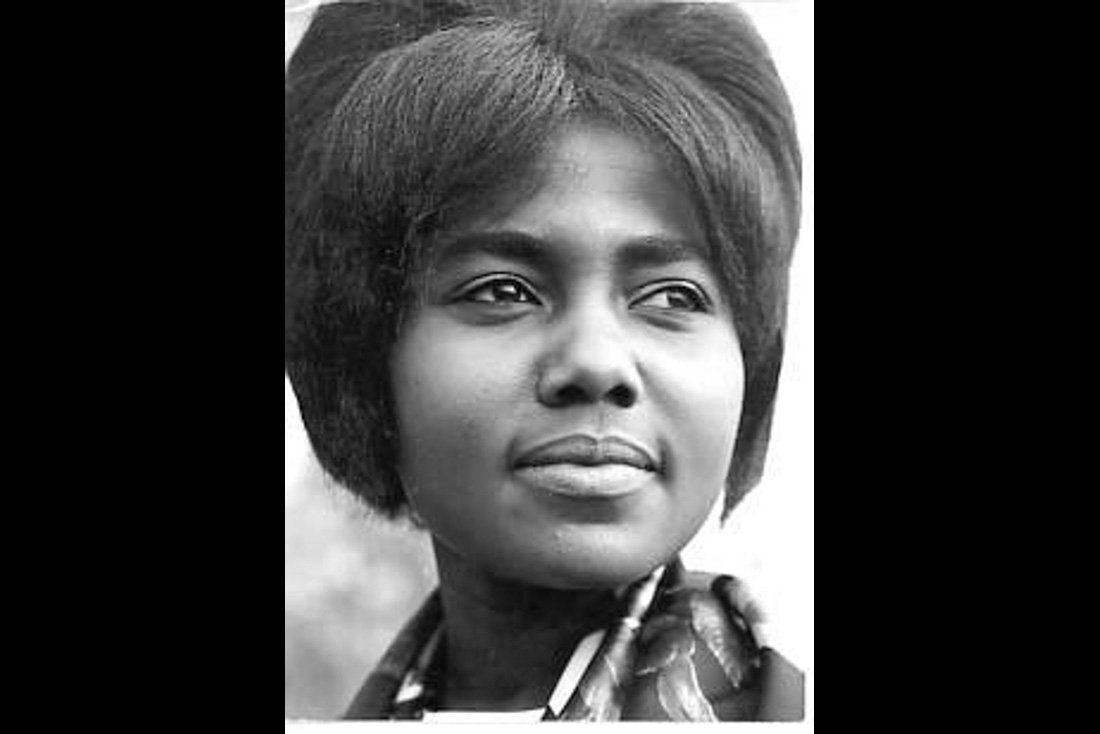

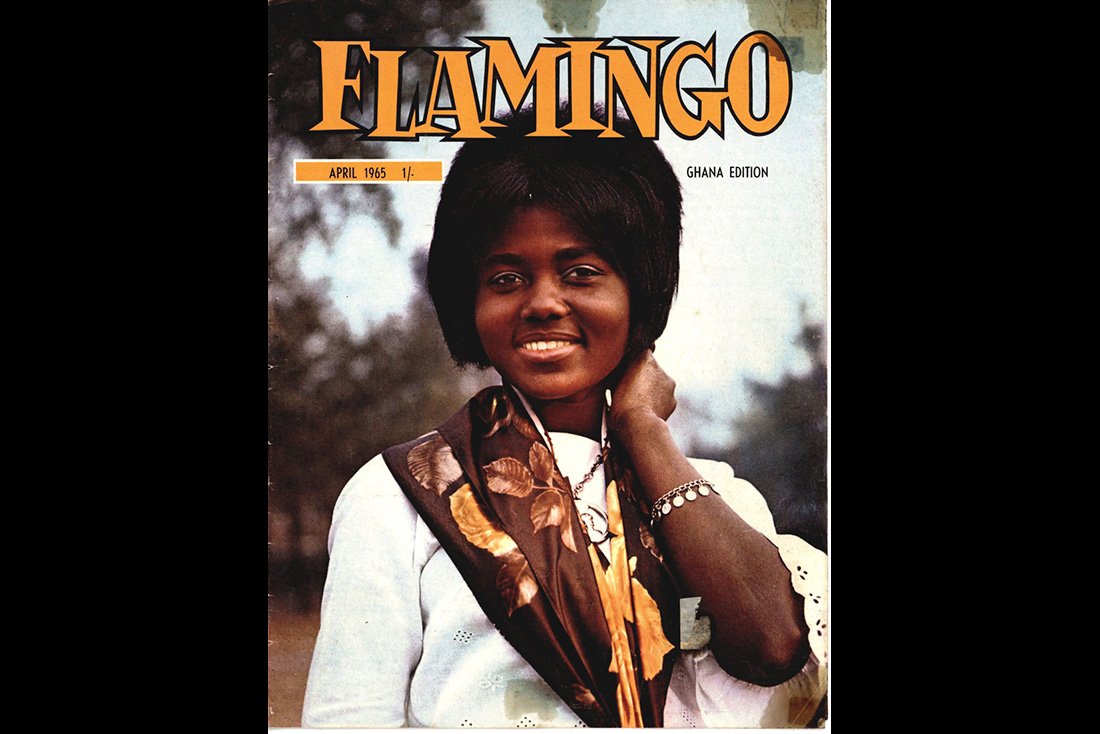

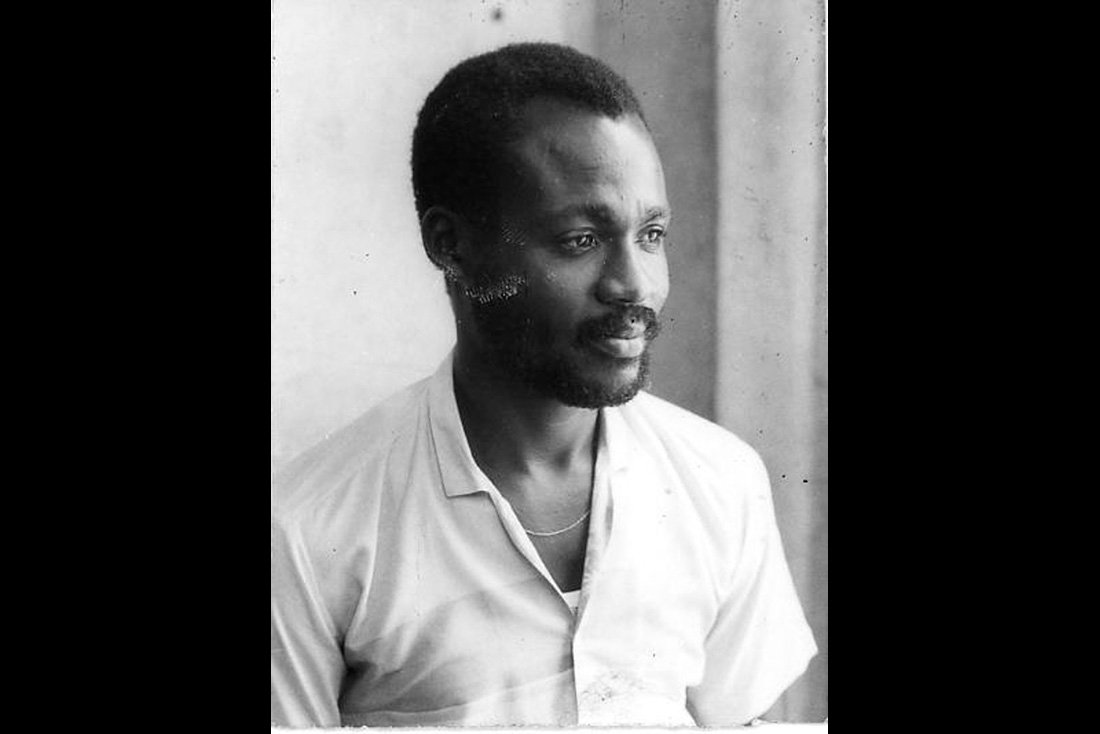

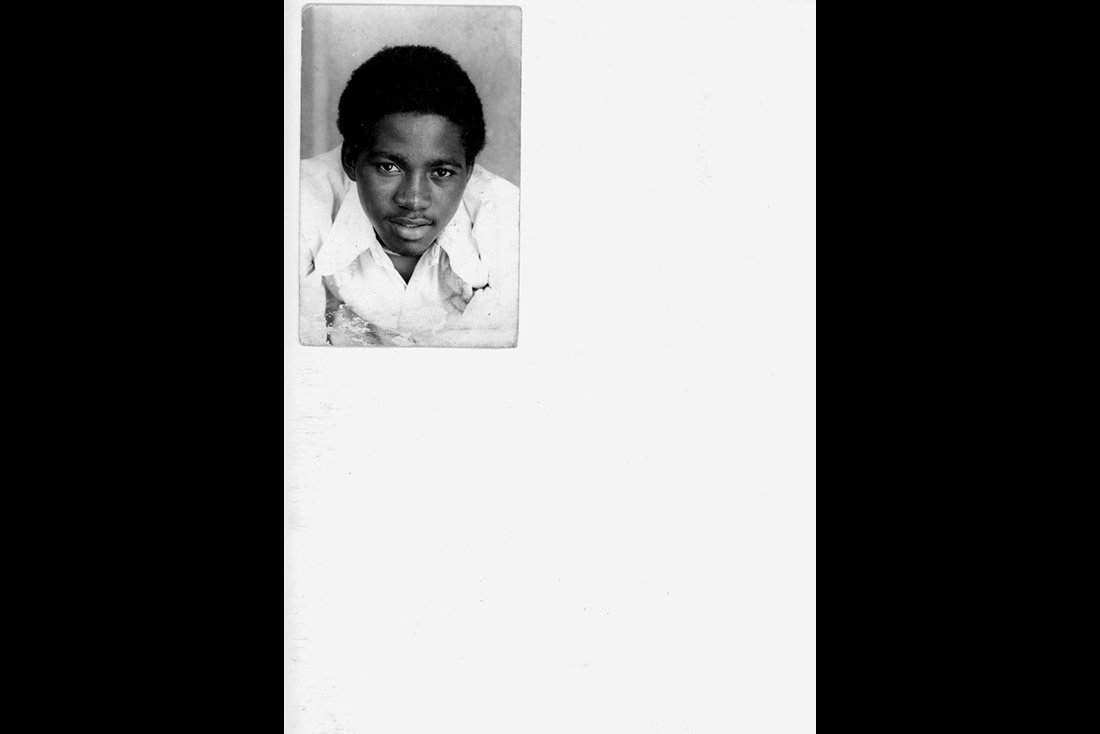

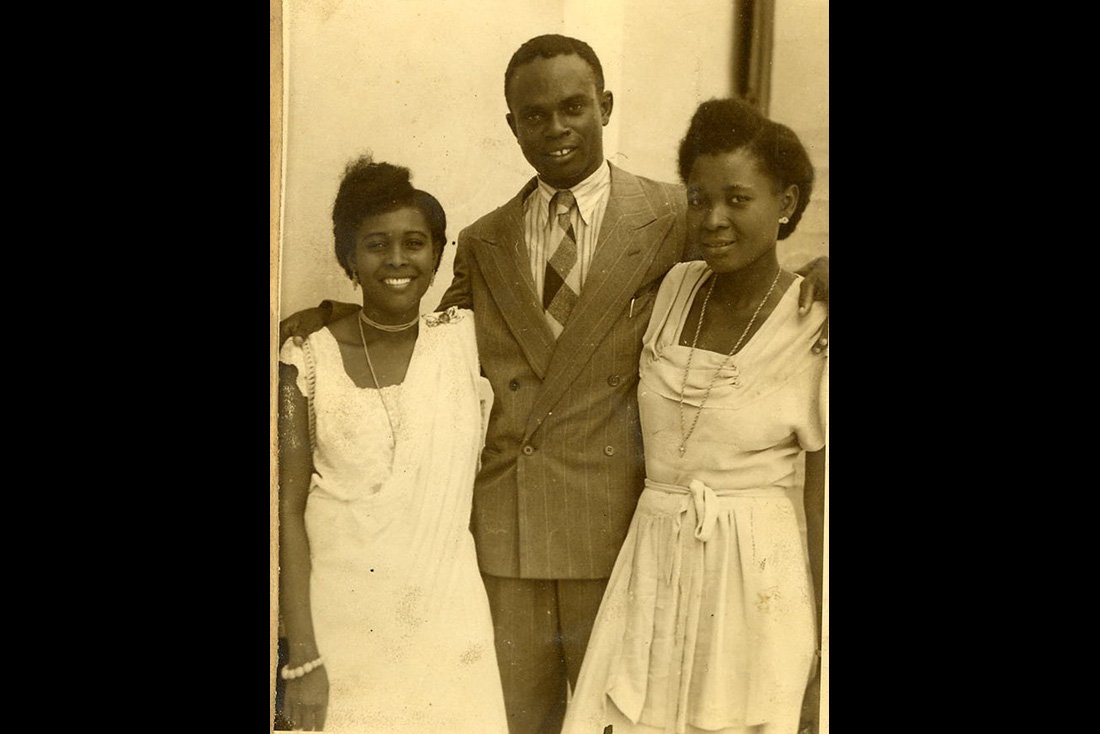

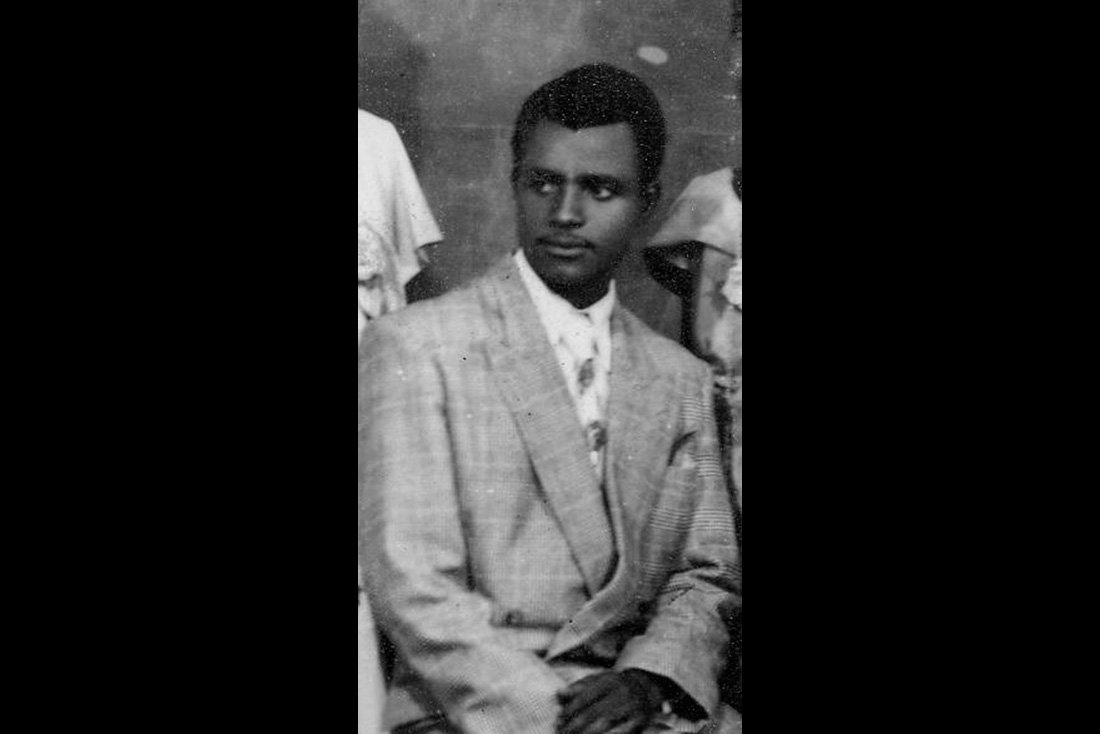

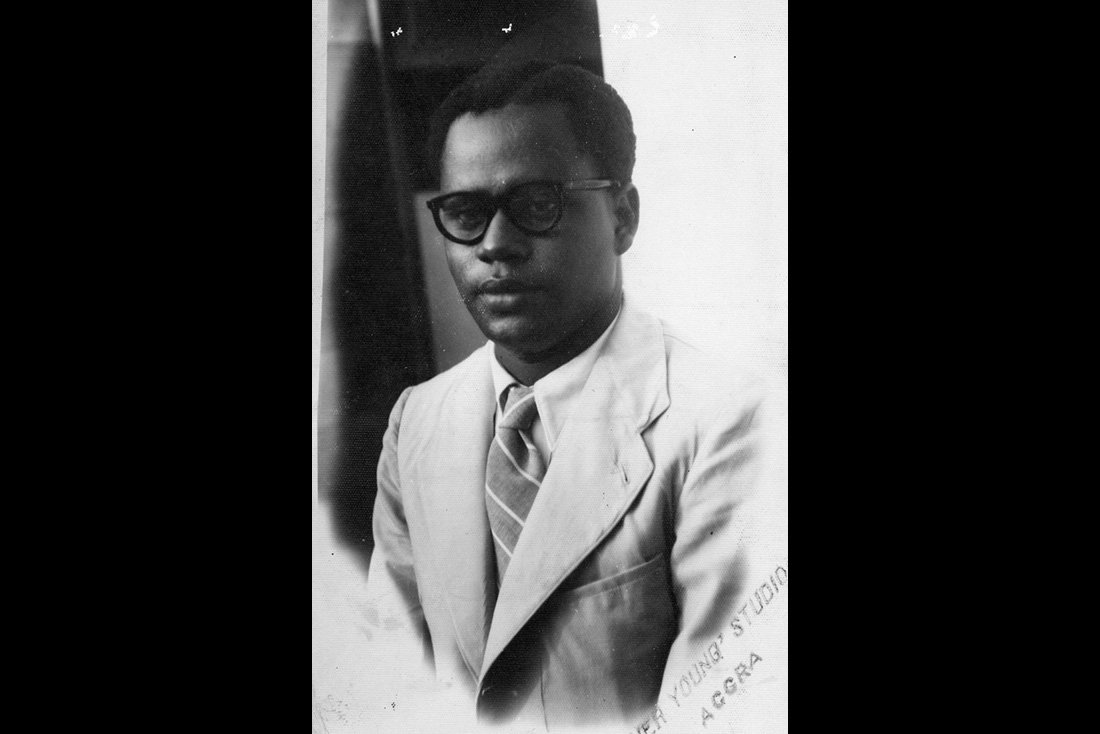

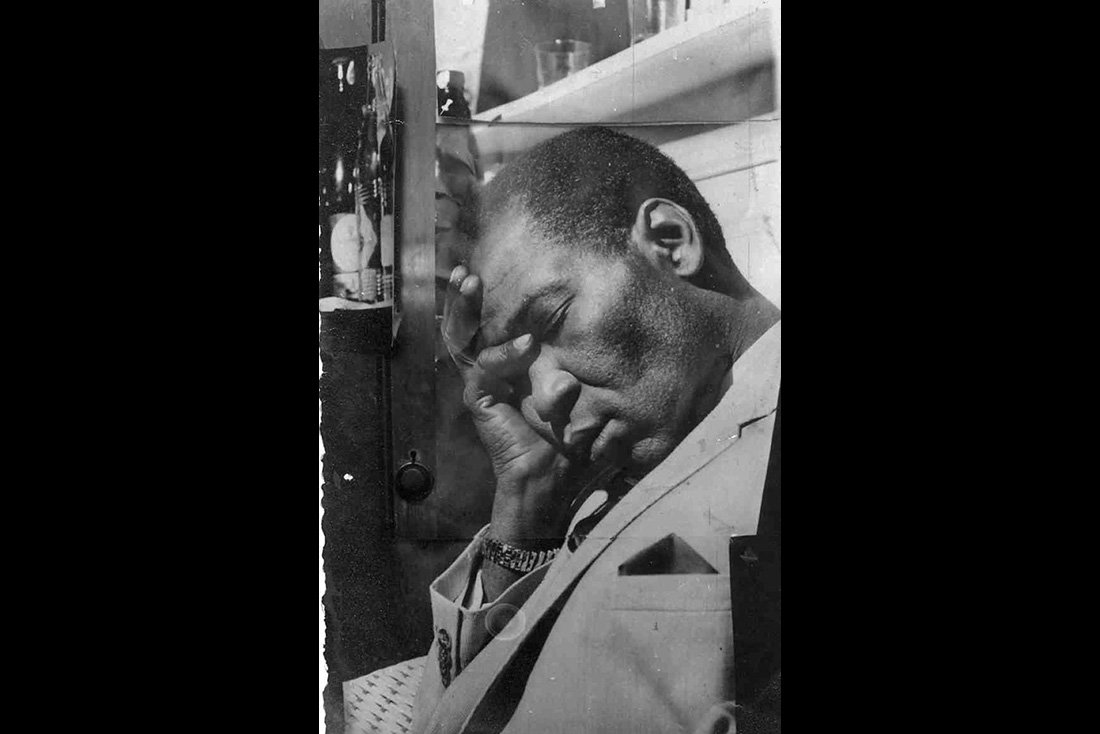

In 2007, at the celebration of fifty years of Ghana’s Independence, Nana Oforiatta Ayim met a photographer, then in his late seventies, who had never had an exhibition, but whose work held a wealth of material. This begun an ongoing process with Ghanaian photographer James Barnor, in which ANO are still working on the digitisation and publication of a monograph on his work.

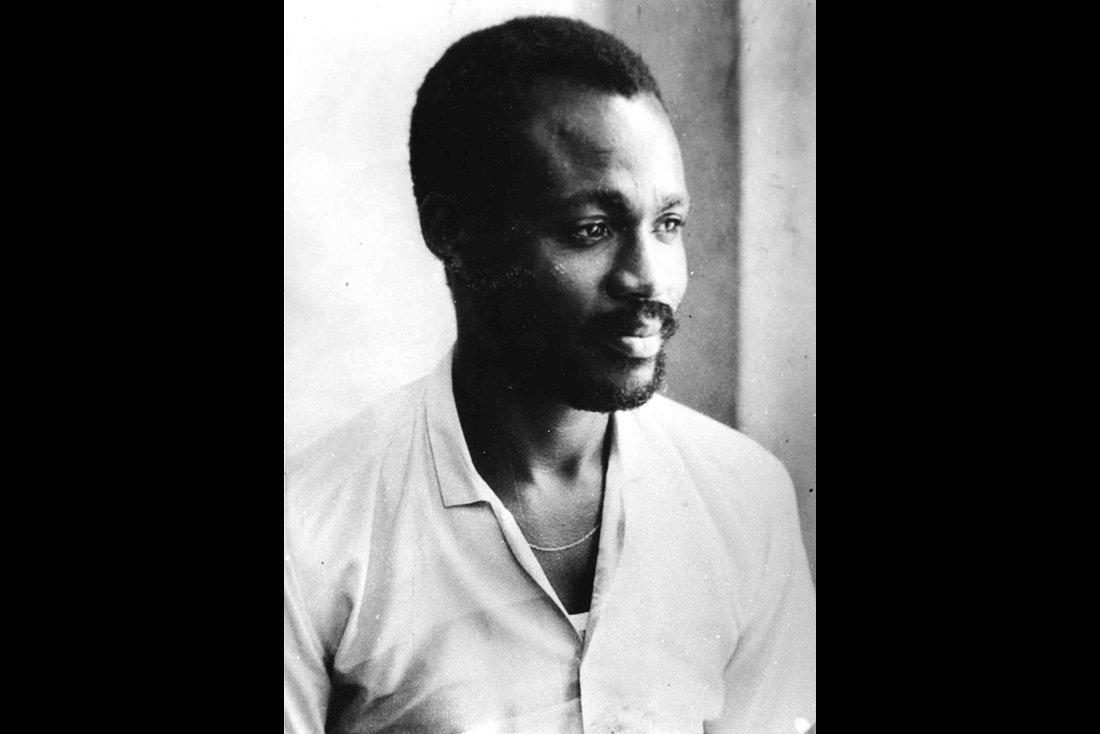

At the time, ANO had the first comprehensive exhibition of his work at the Black Cultural Archives. His work spoke of a history of modernity in West Africa that I had never seen expressed so eloquently.

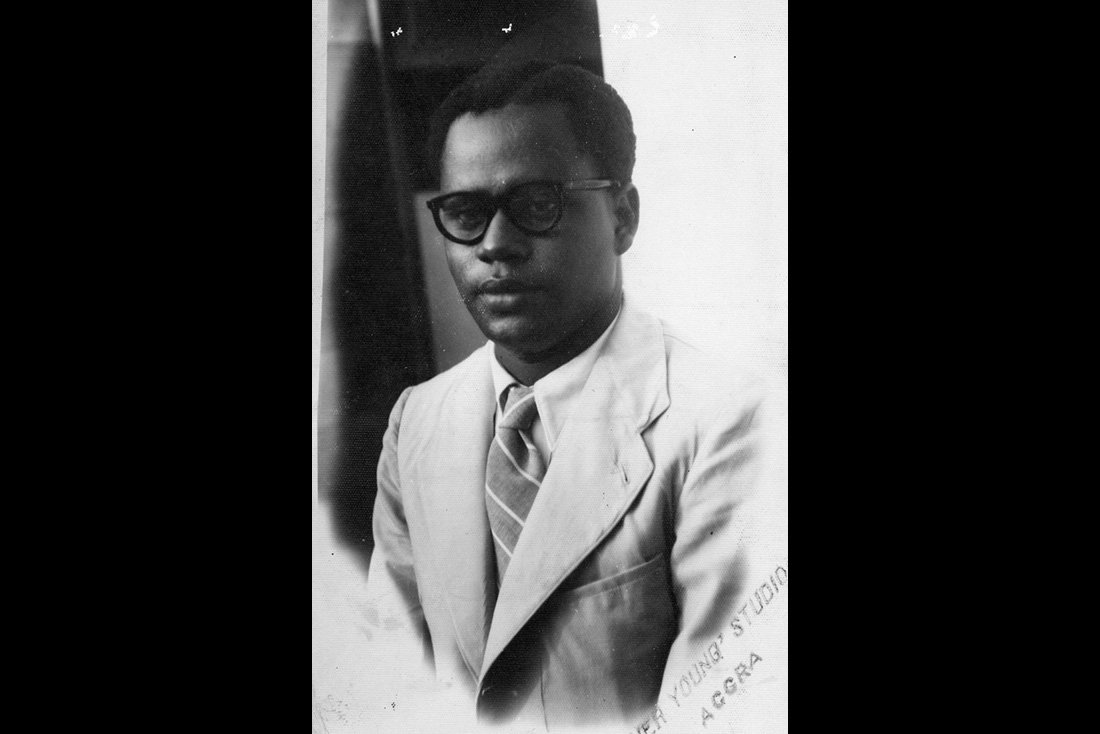

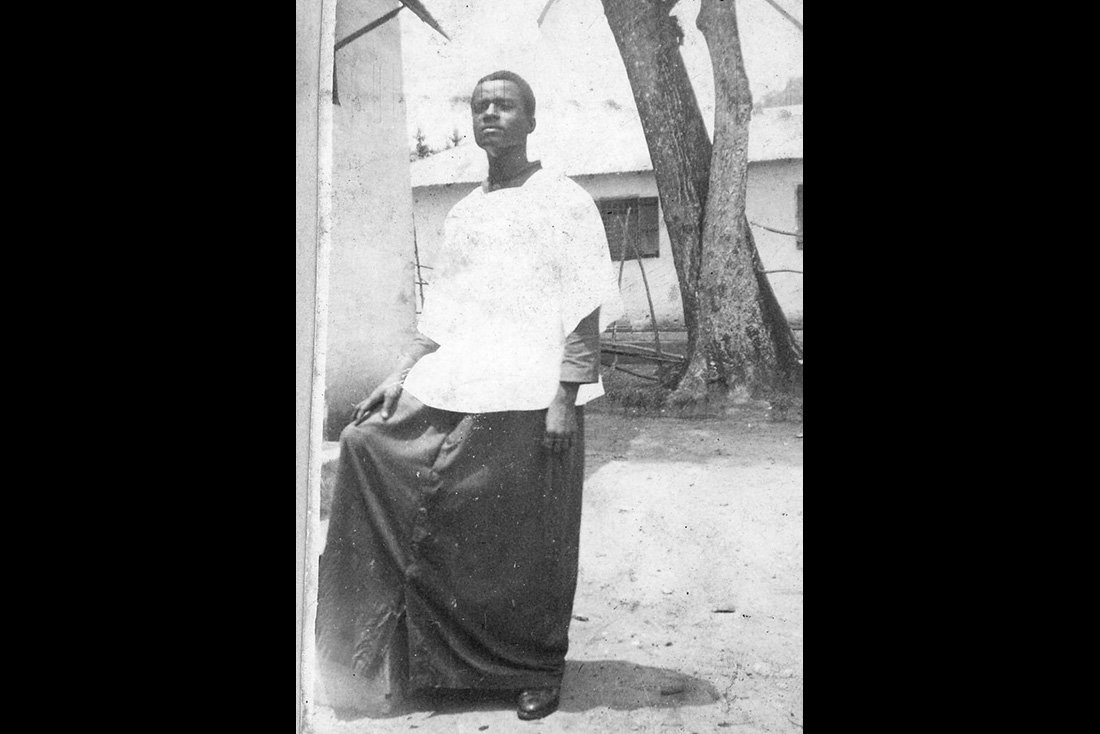

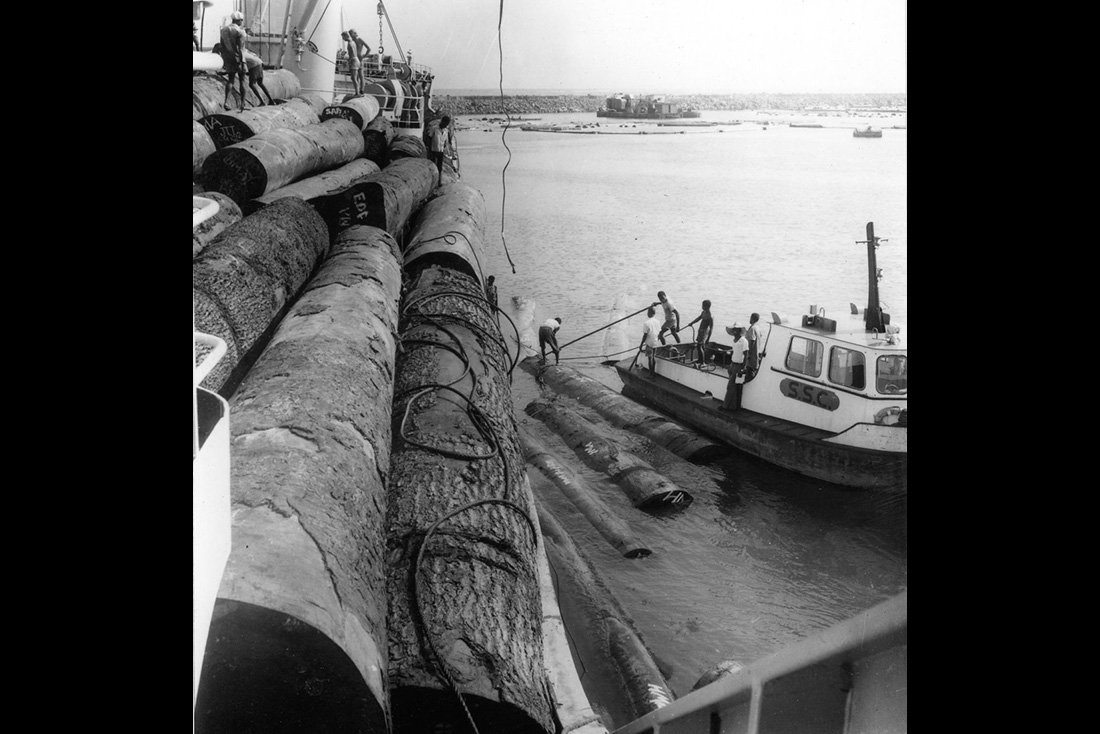

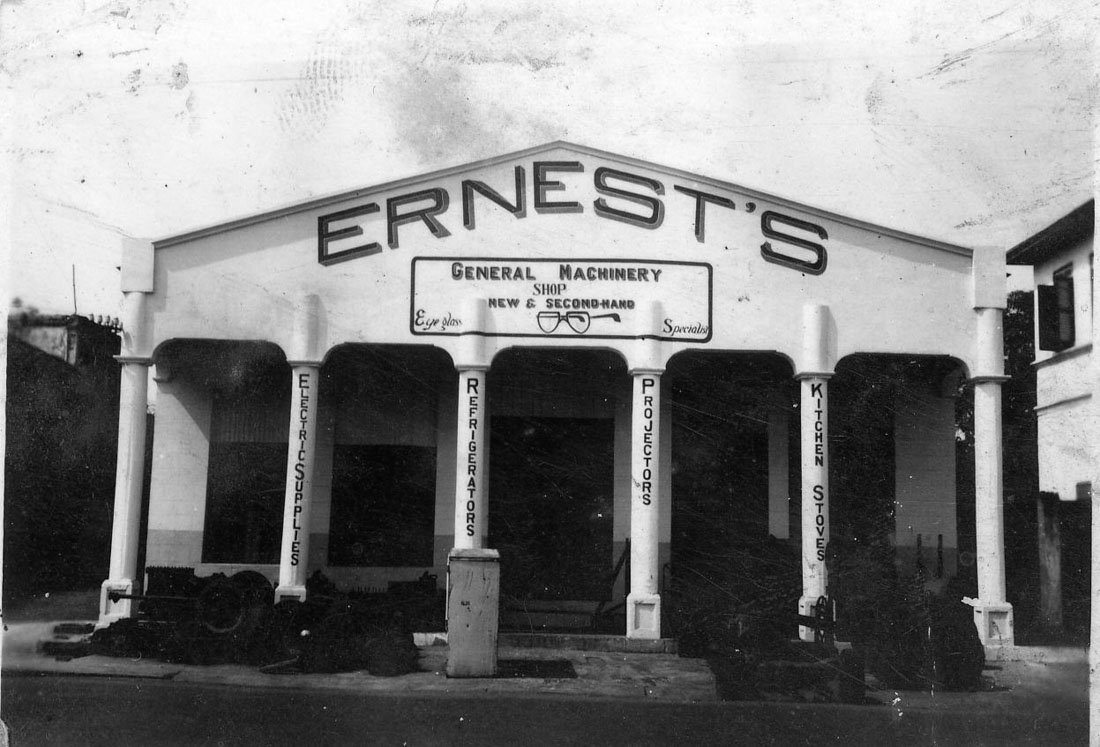

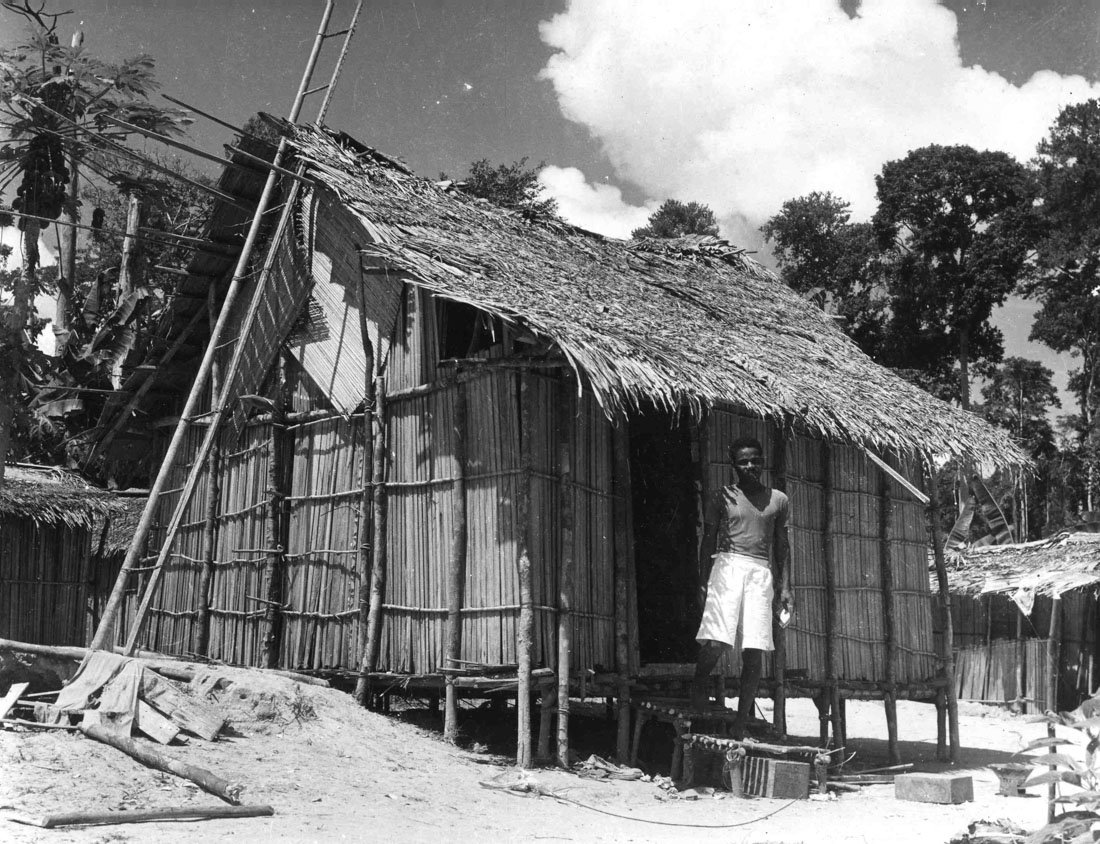

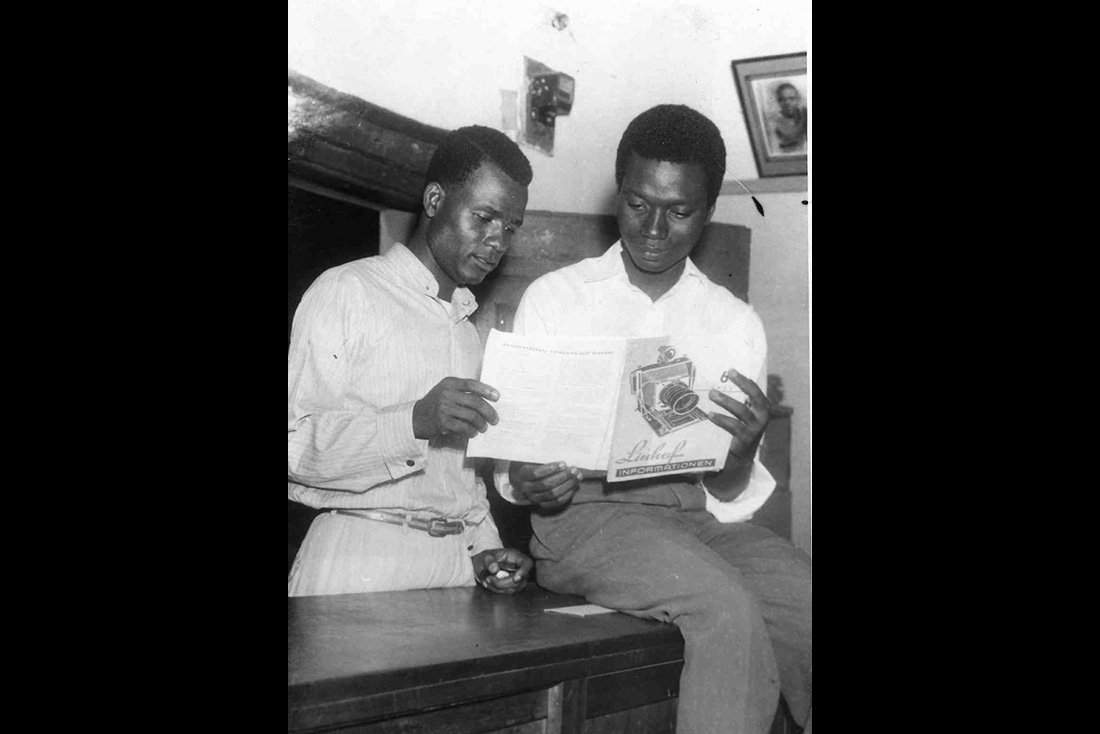

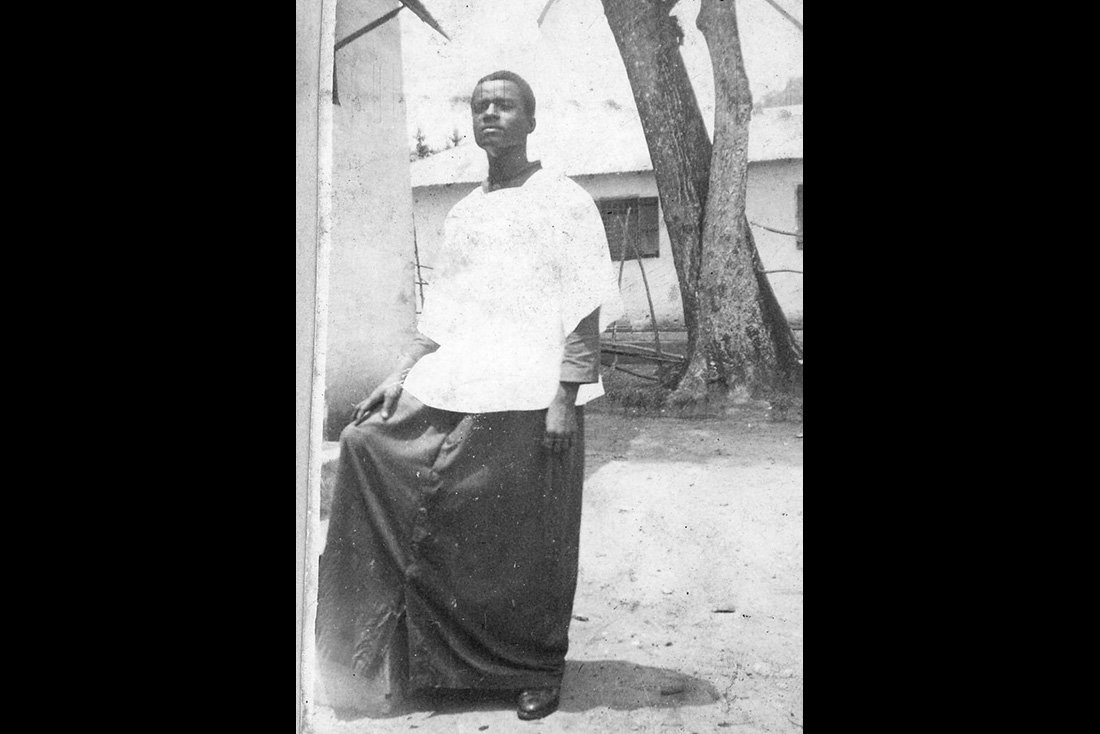

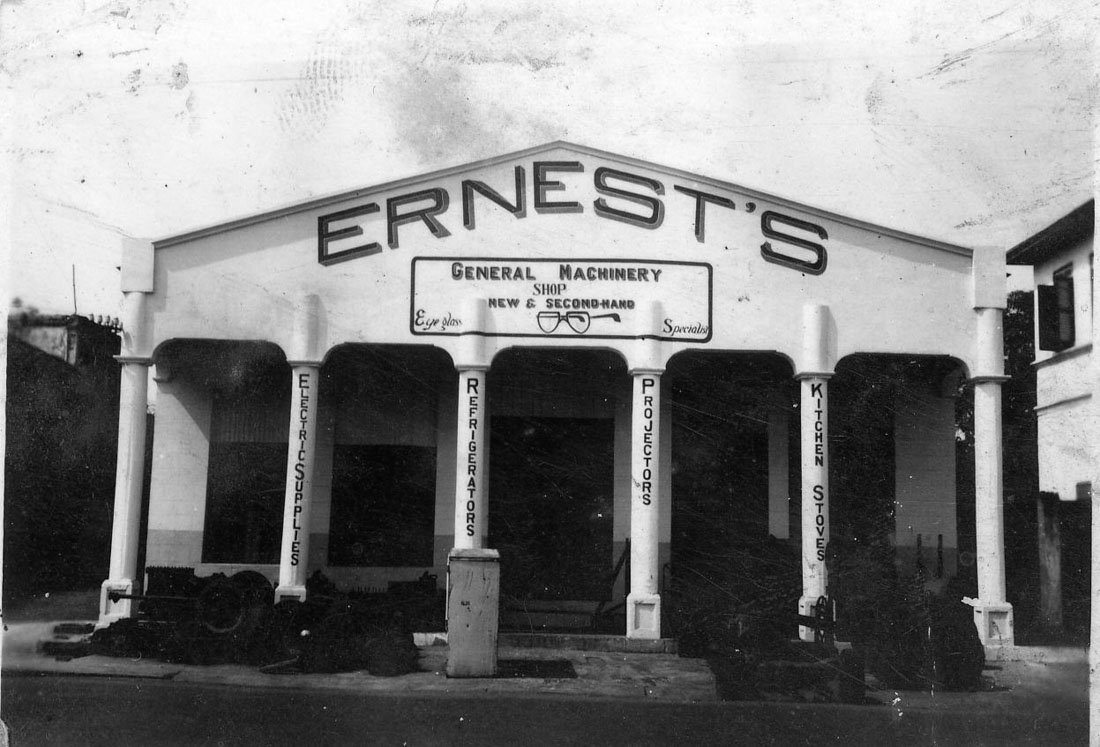

With it being precipitated through trade with Europe and the ensuing rise in technology, so that the history of photography in Ghana turned out to be almost as old as it is elsewhere in the world. Only three years after the production of the daguerreotype by Daguerre in 1839, the French captain Bouet produced one in Elmina. Studios proliferated in the 1890s and photographers became active in a number of cities of the West African Coast.

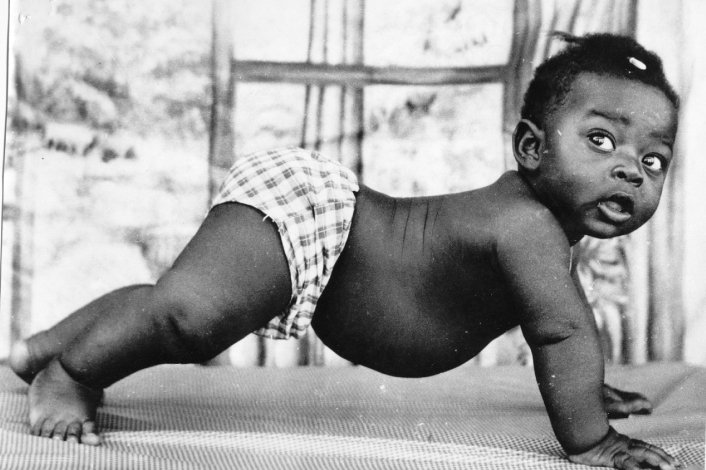

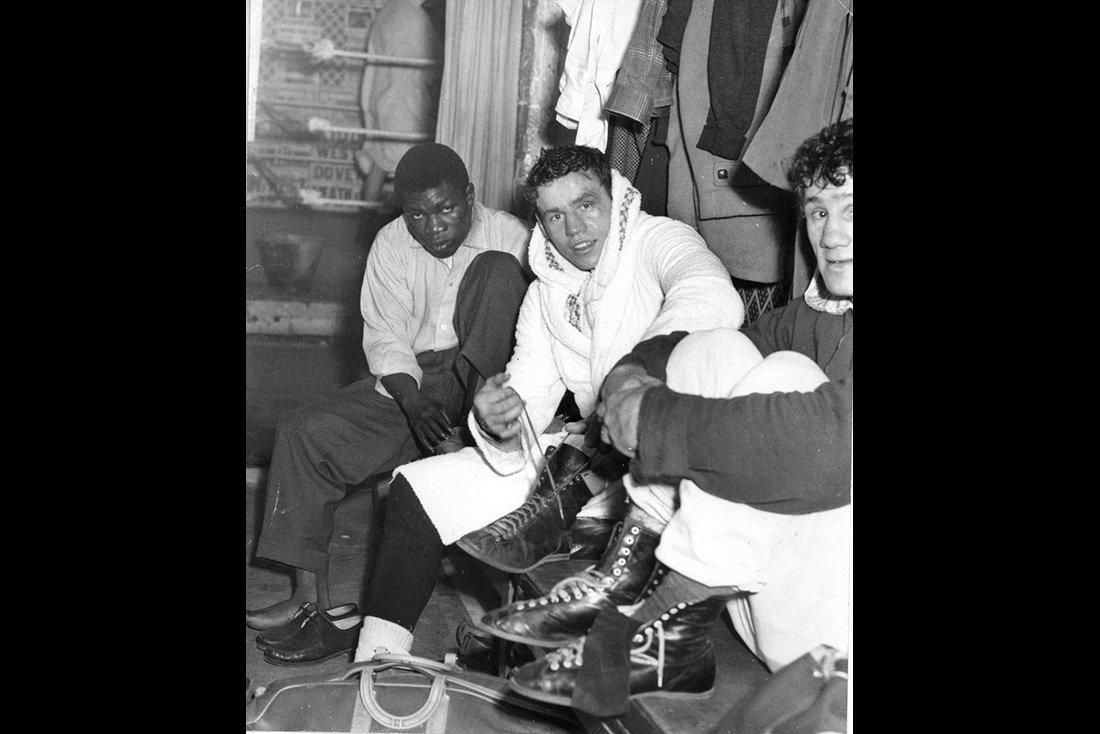

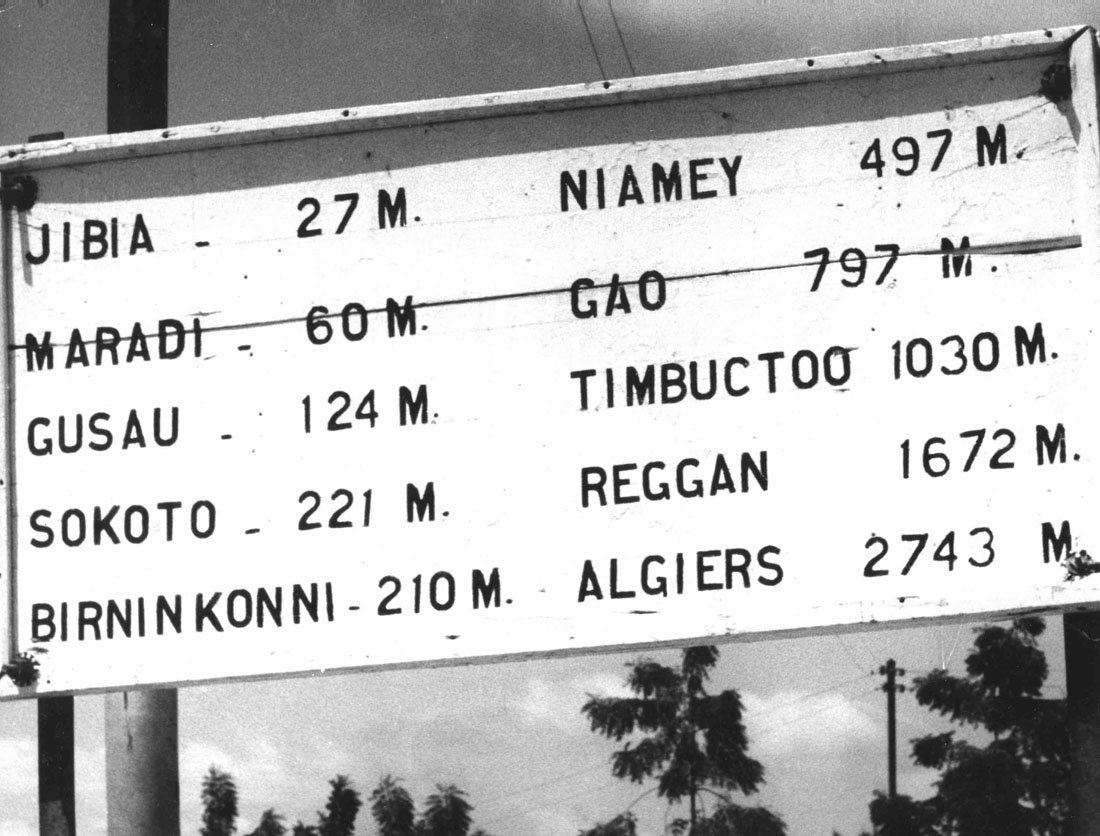

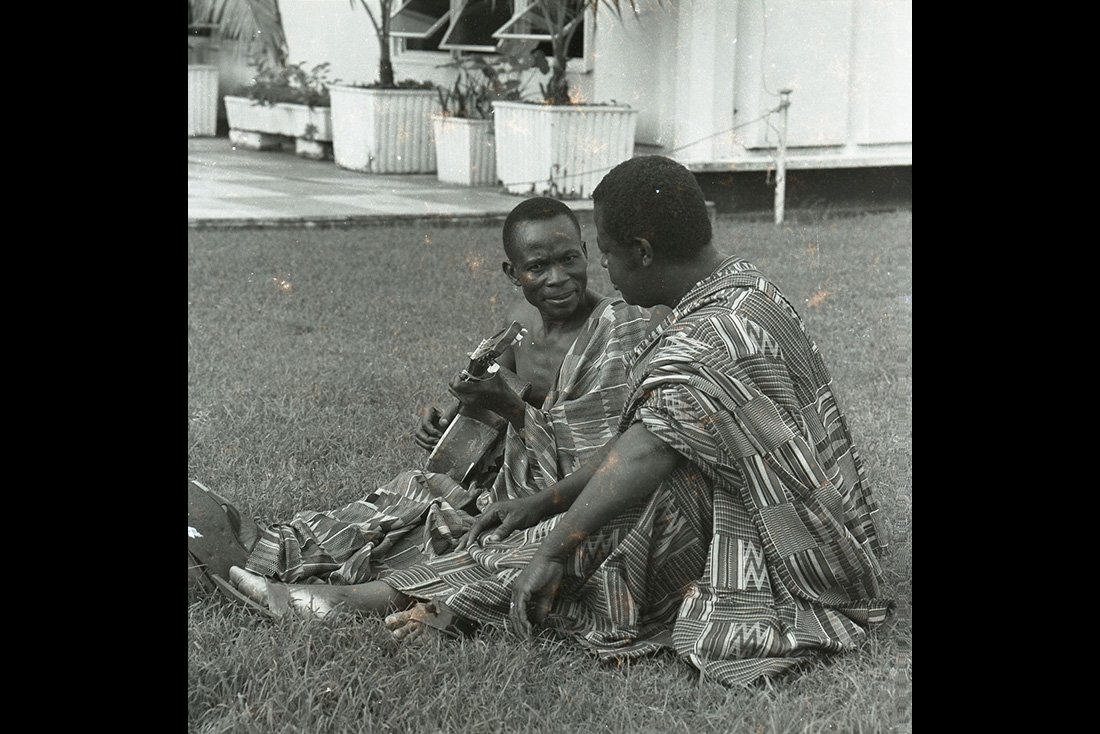

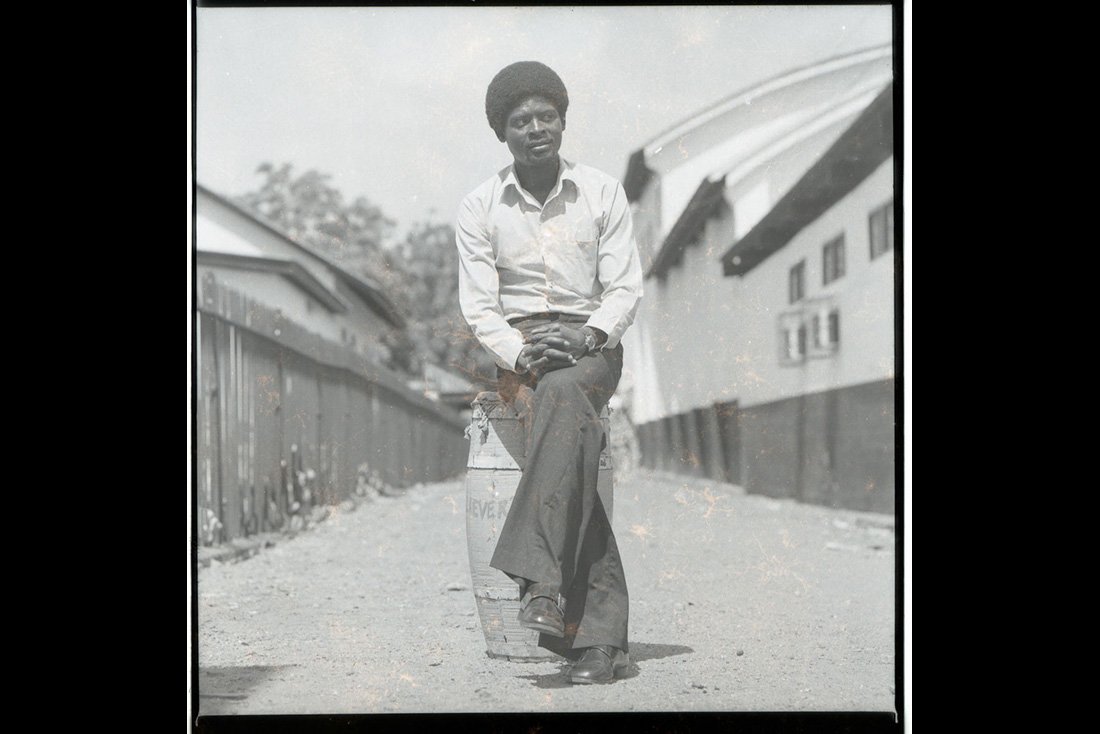

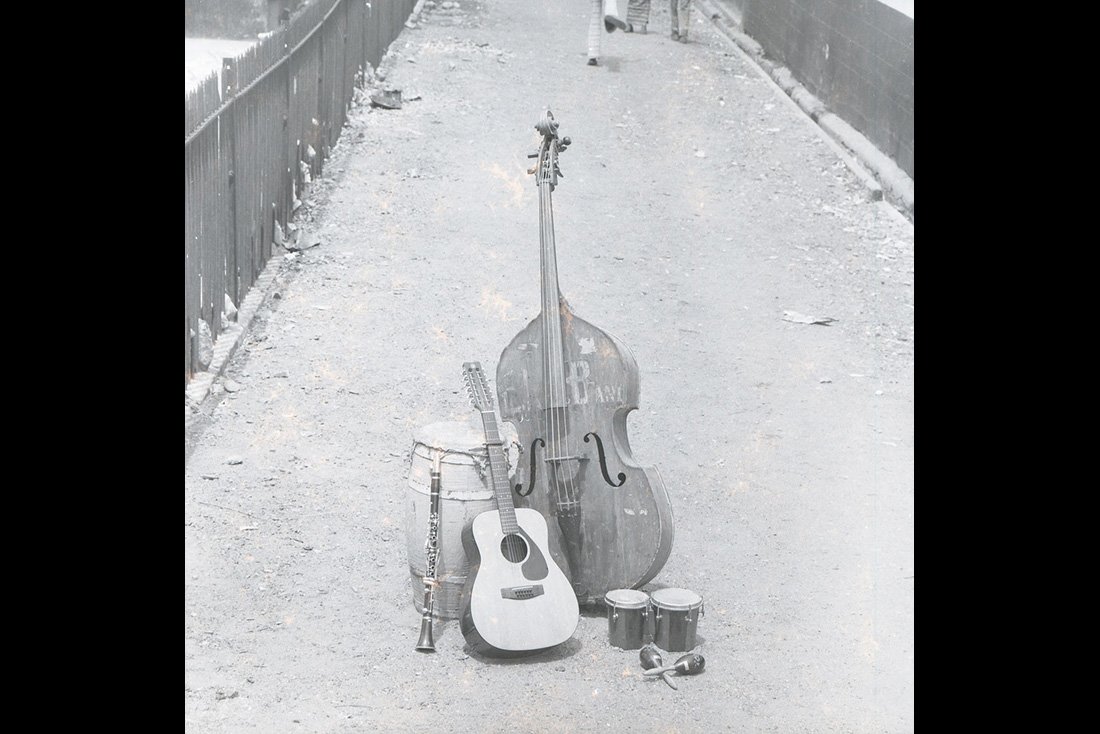

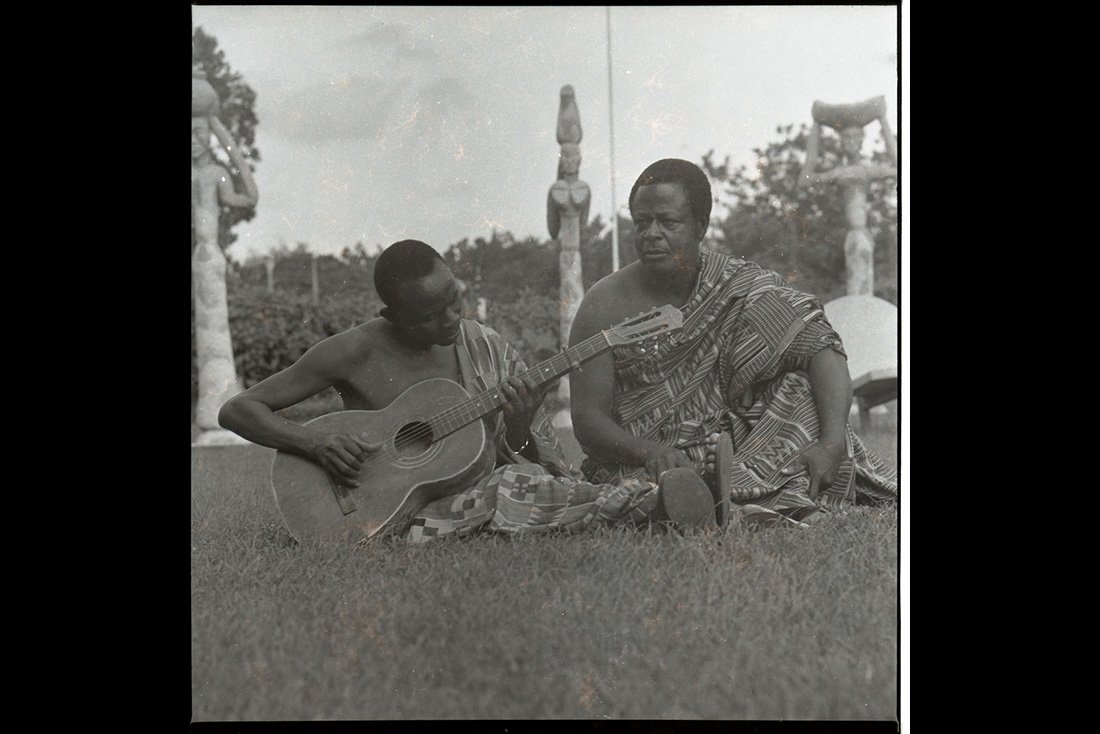

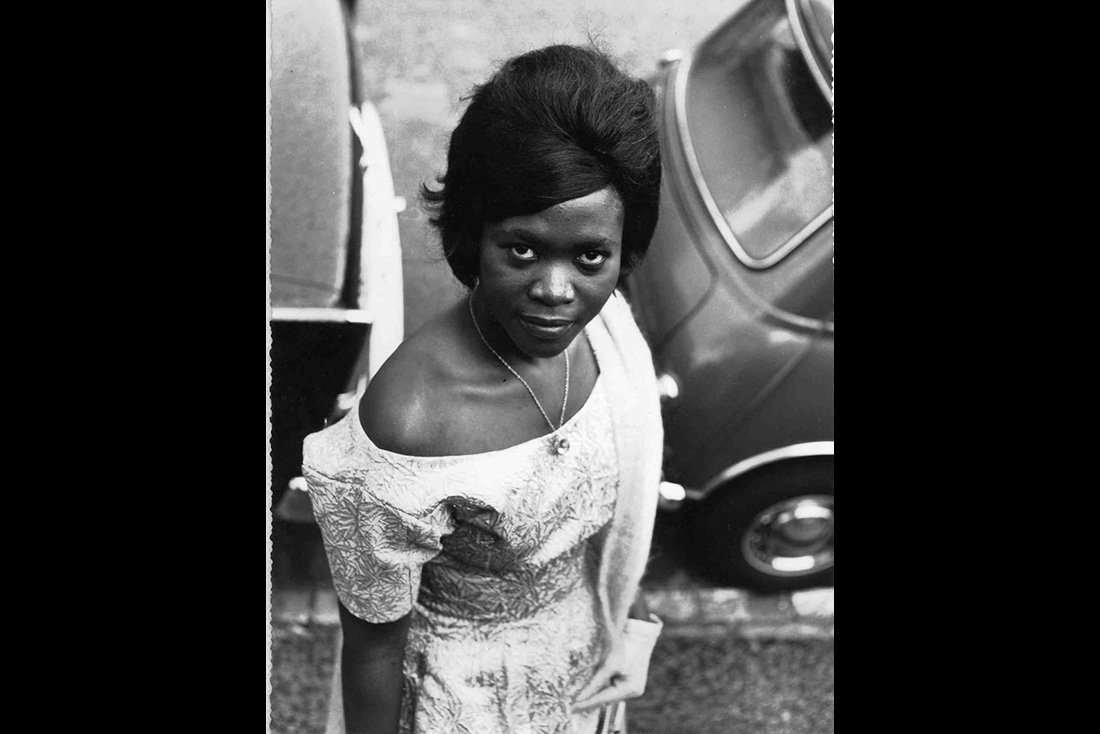

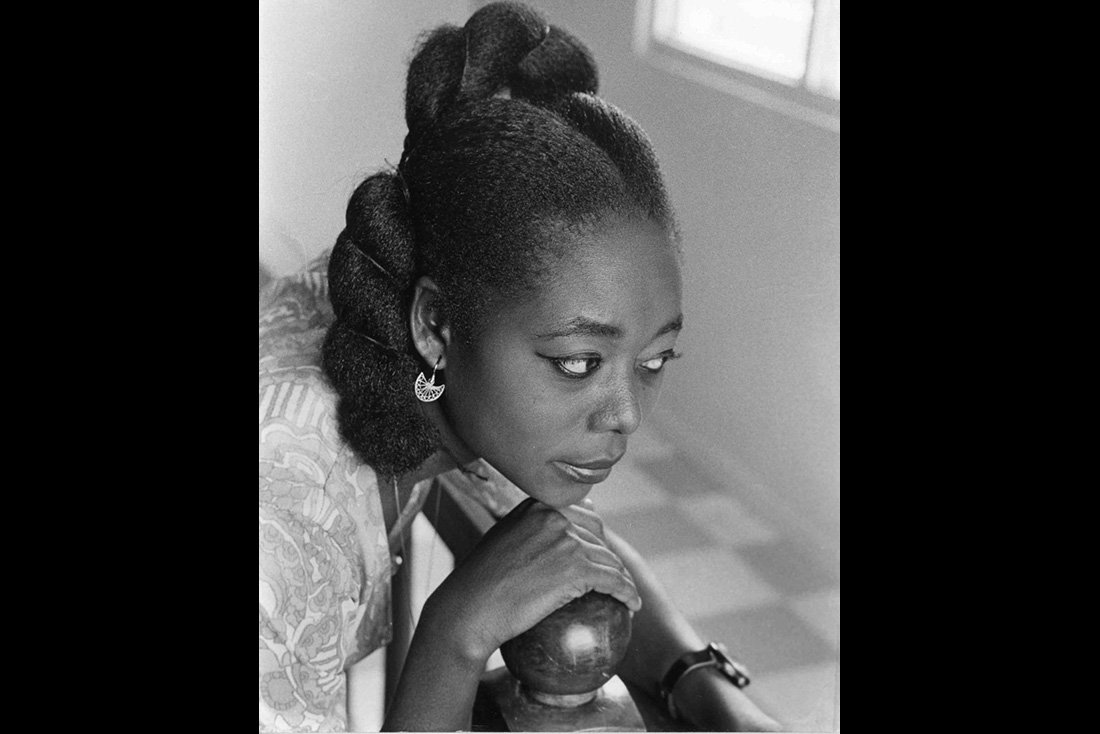

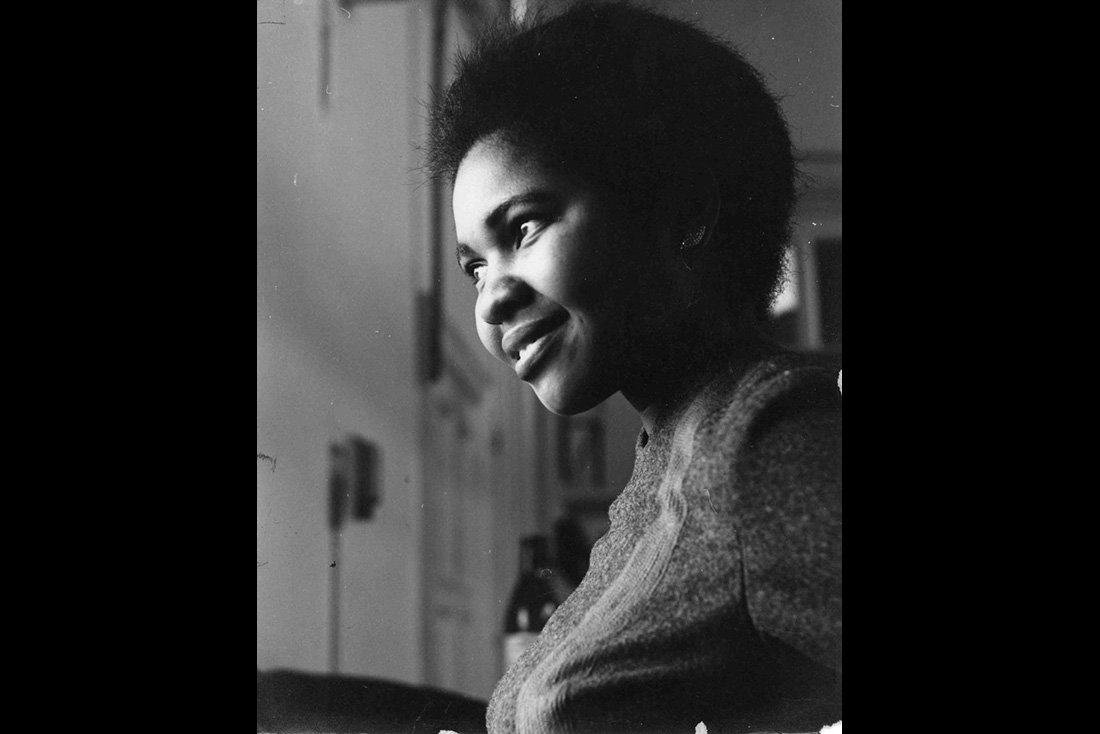

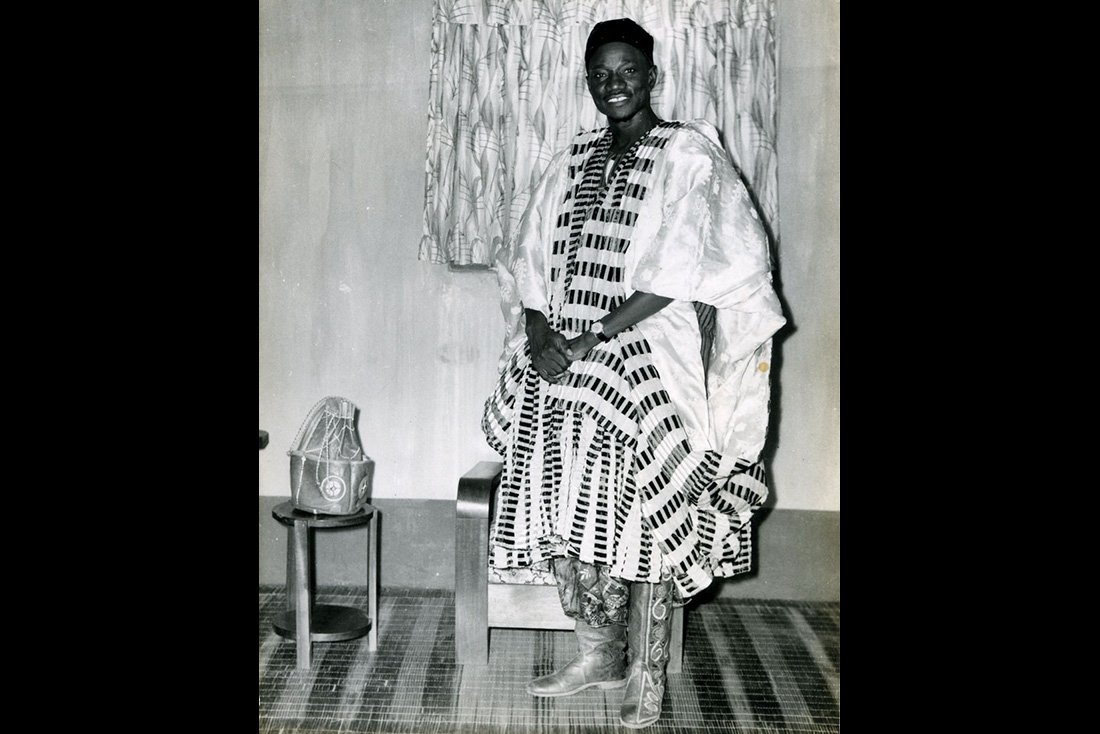

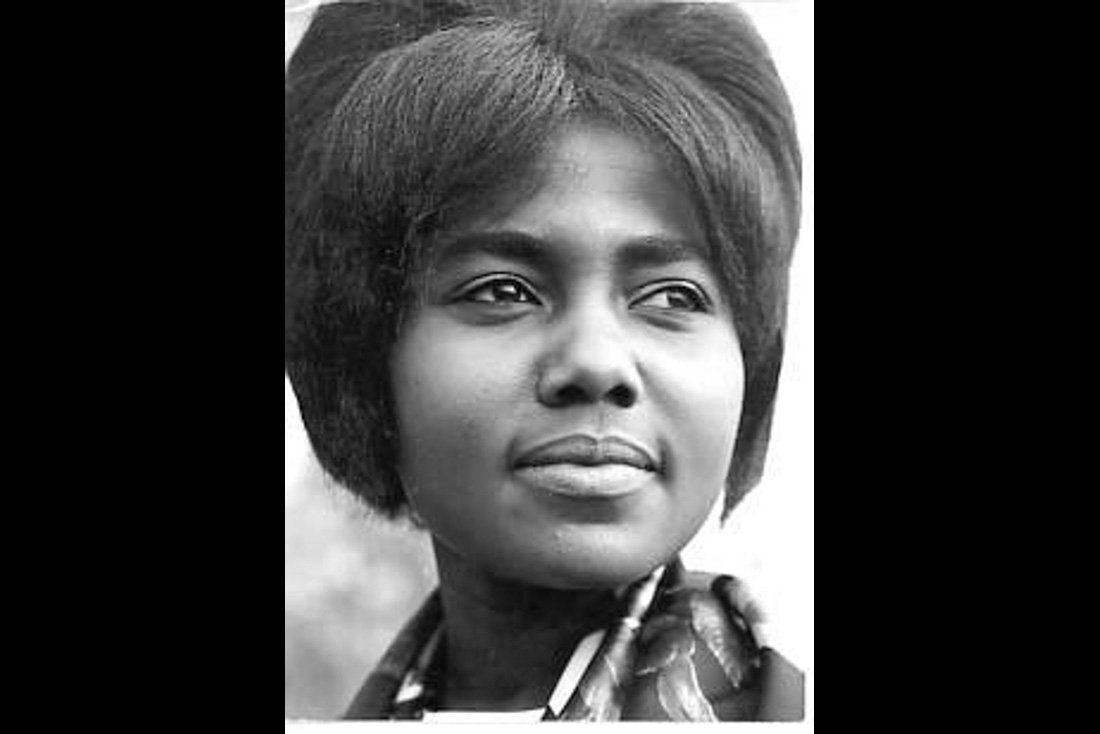

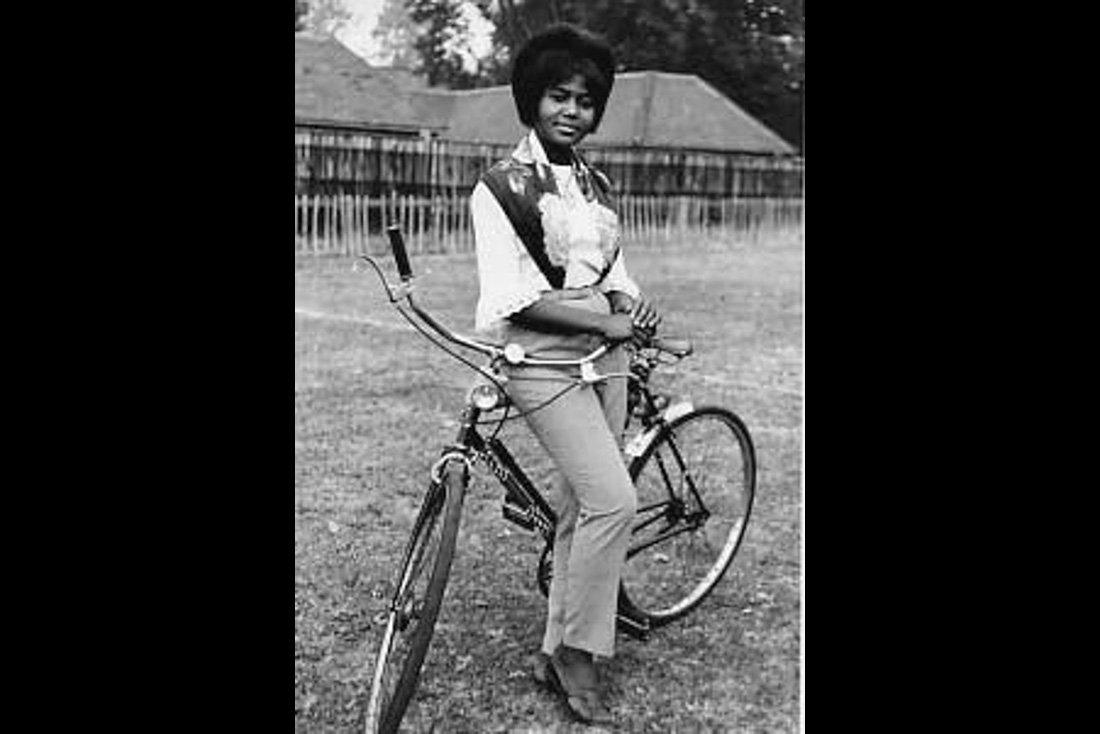

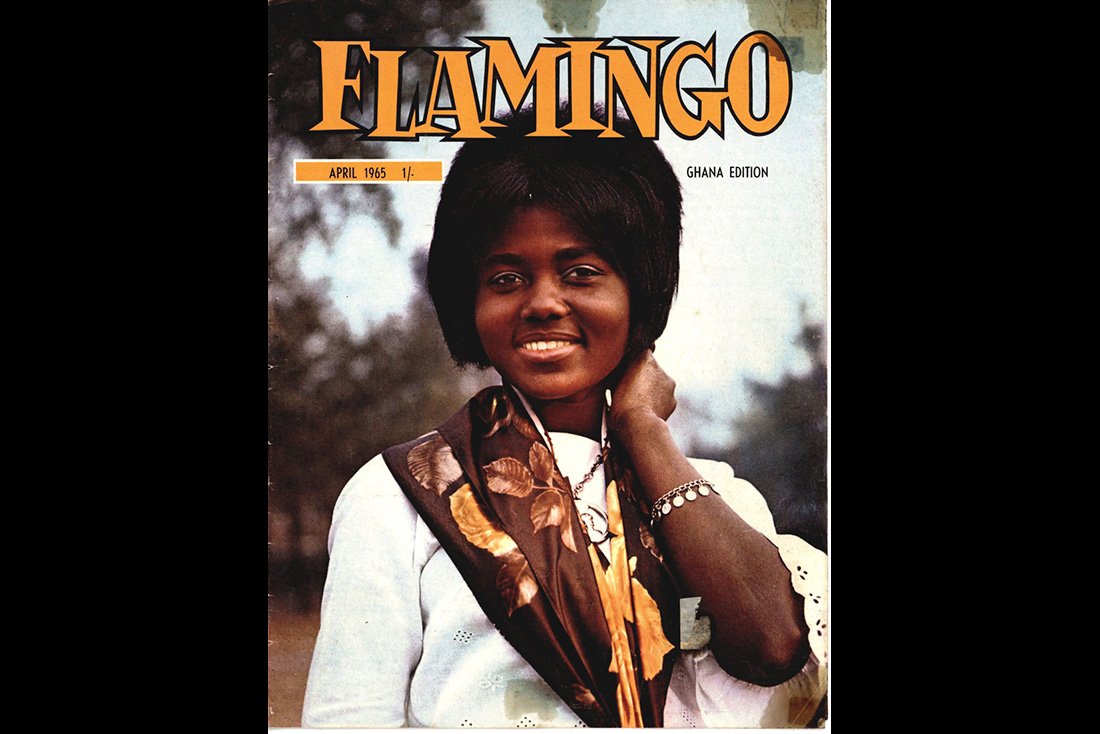

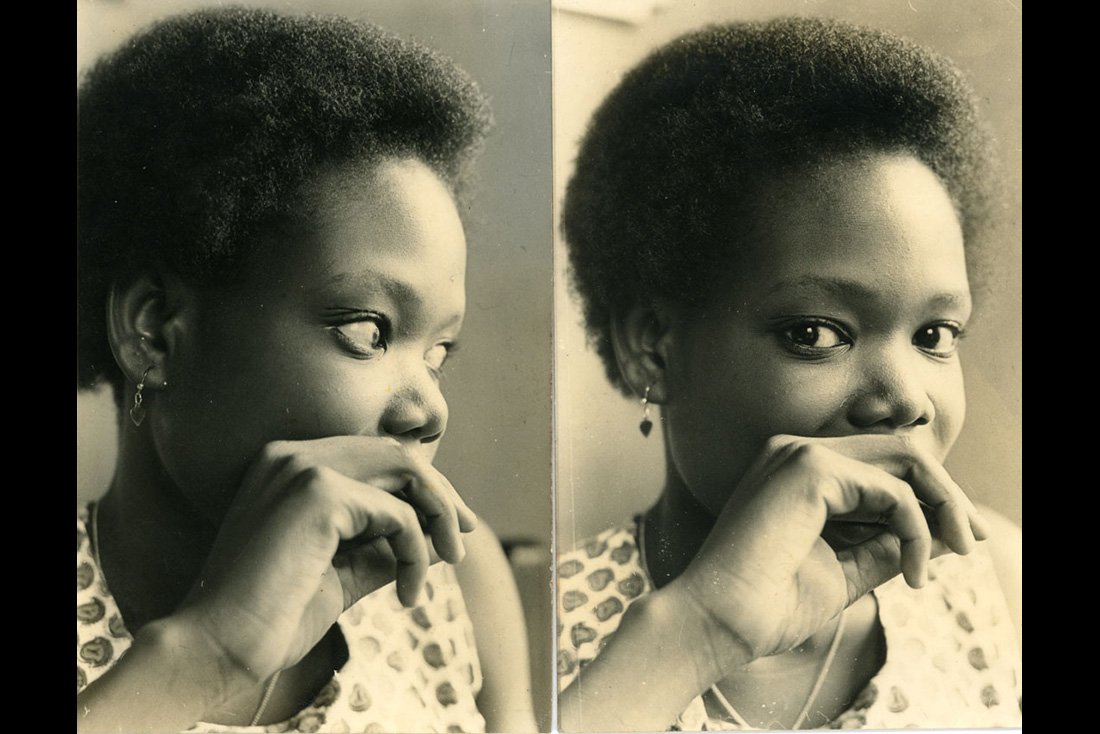

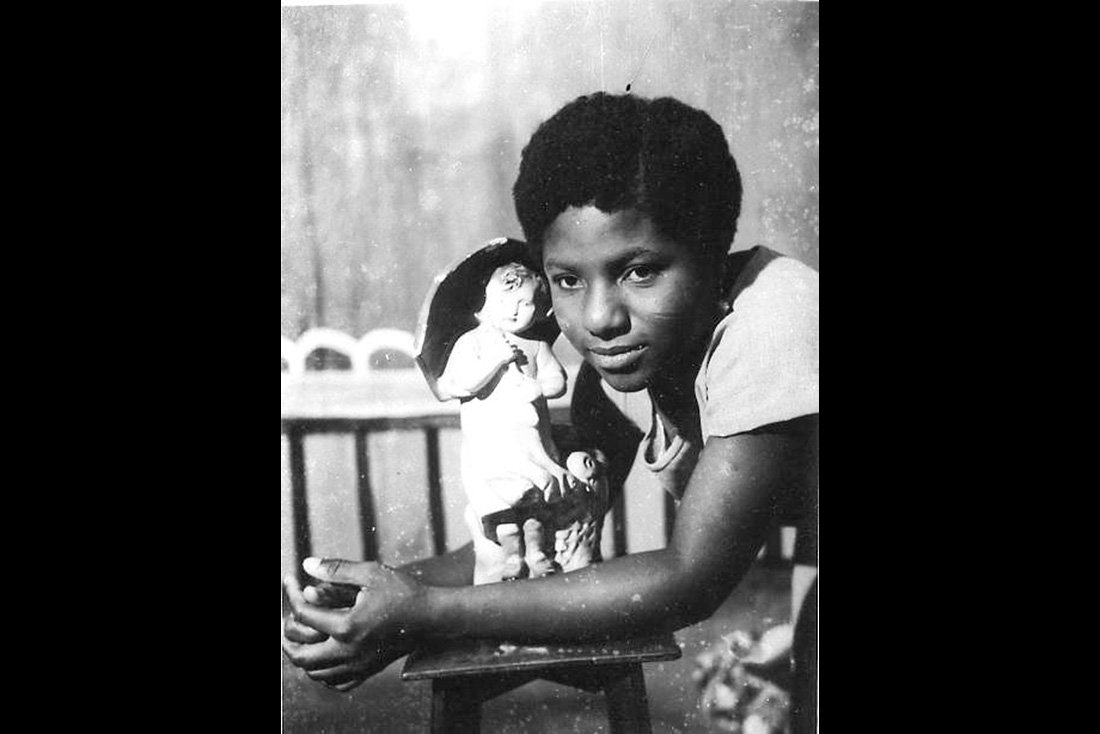

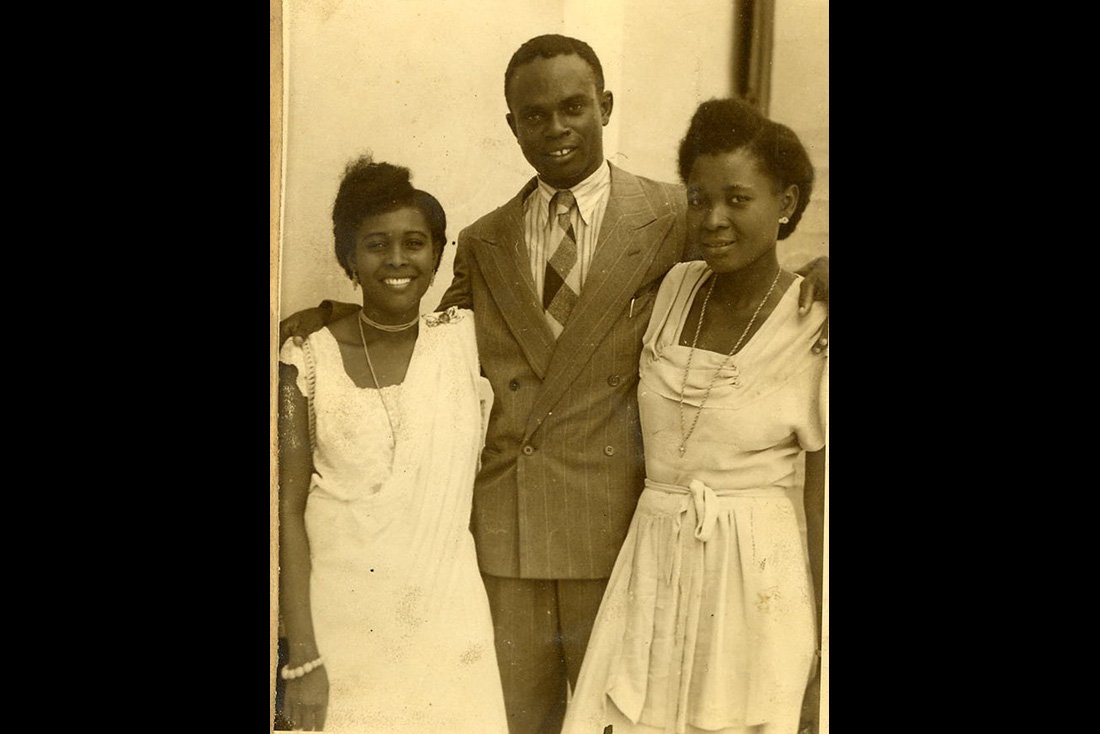

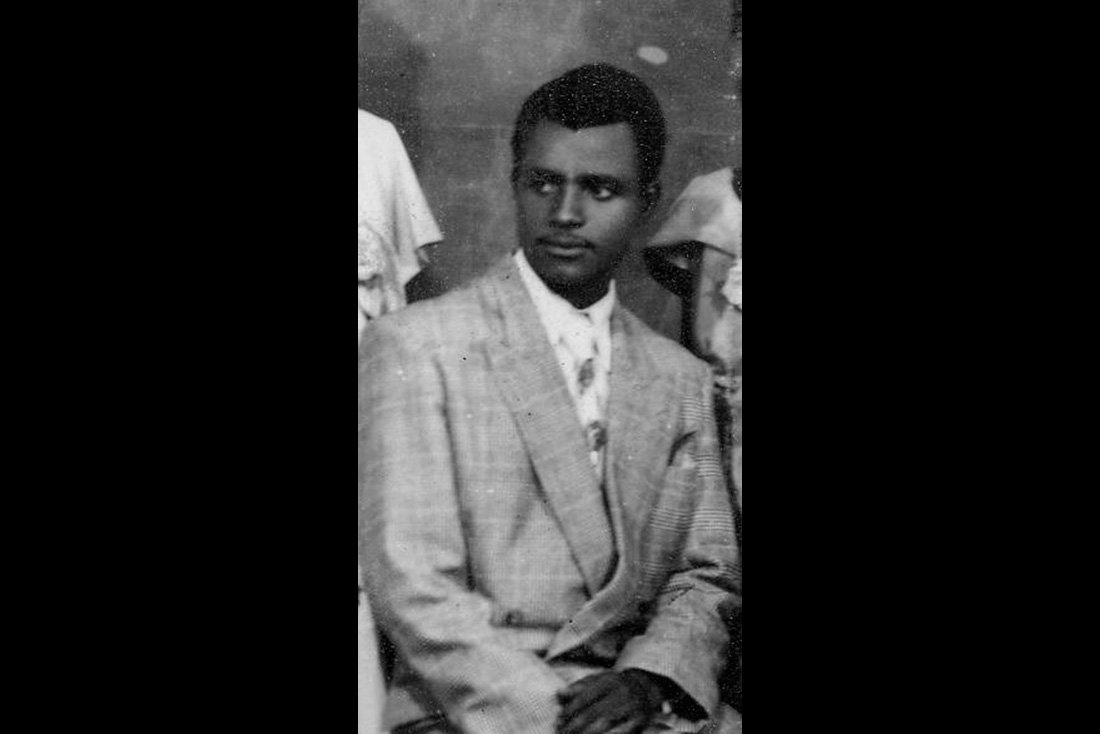

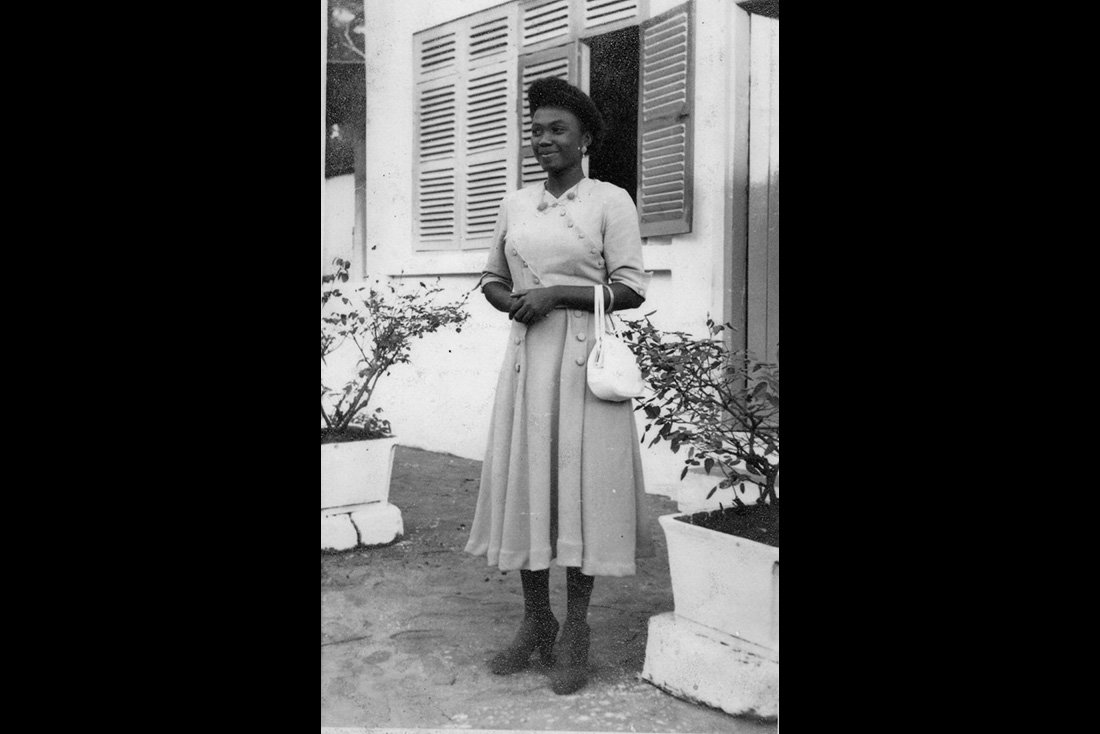

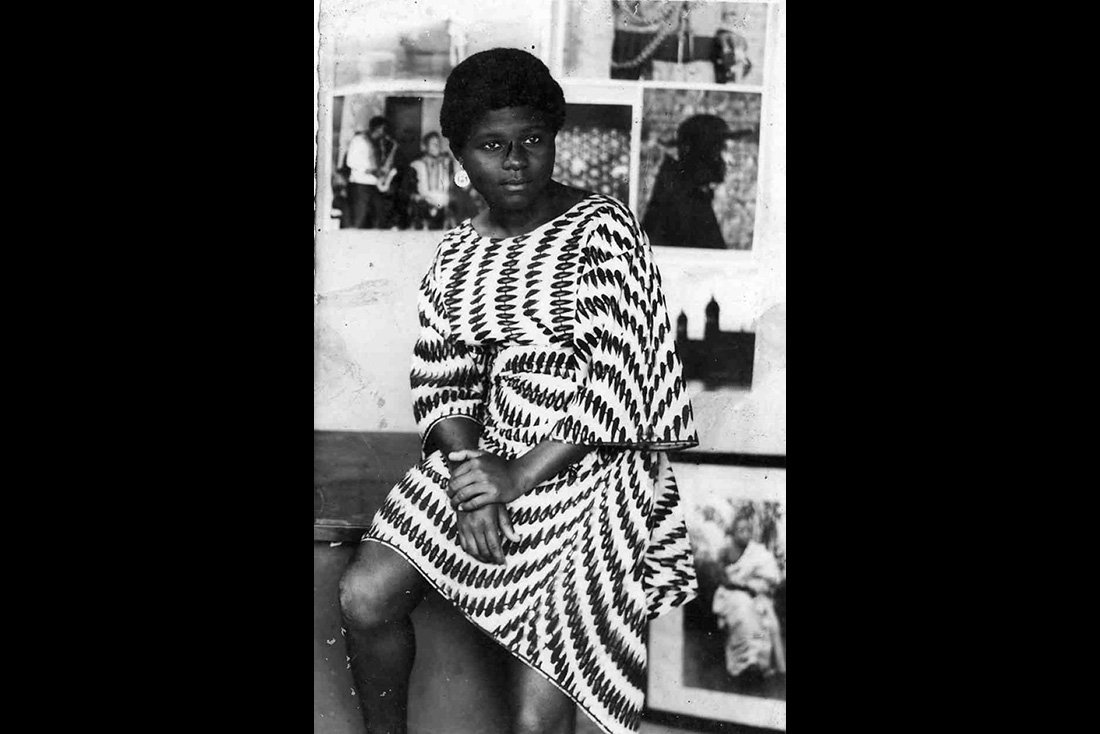

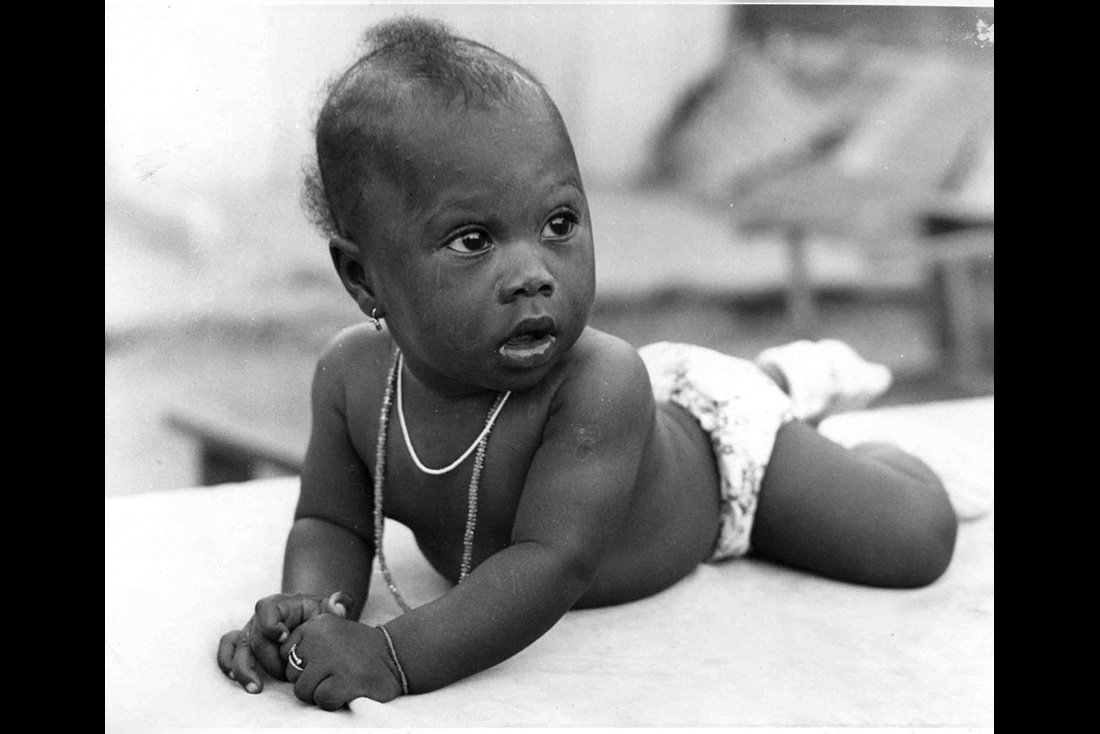

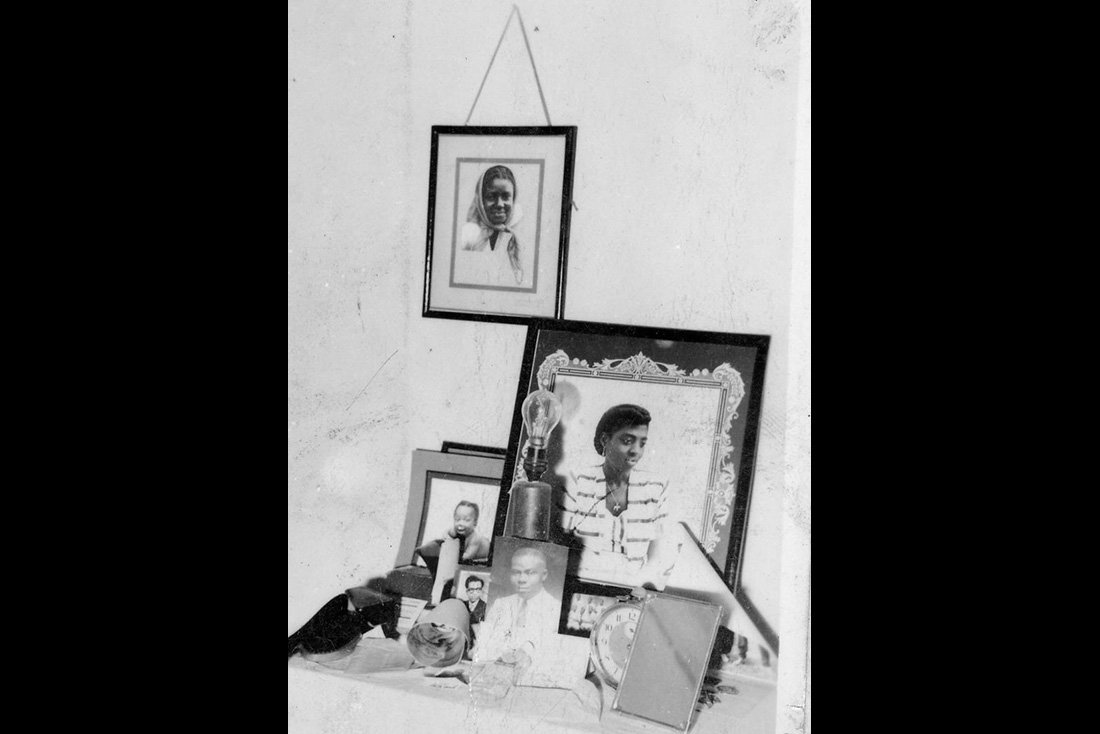

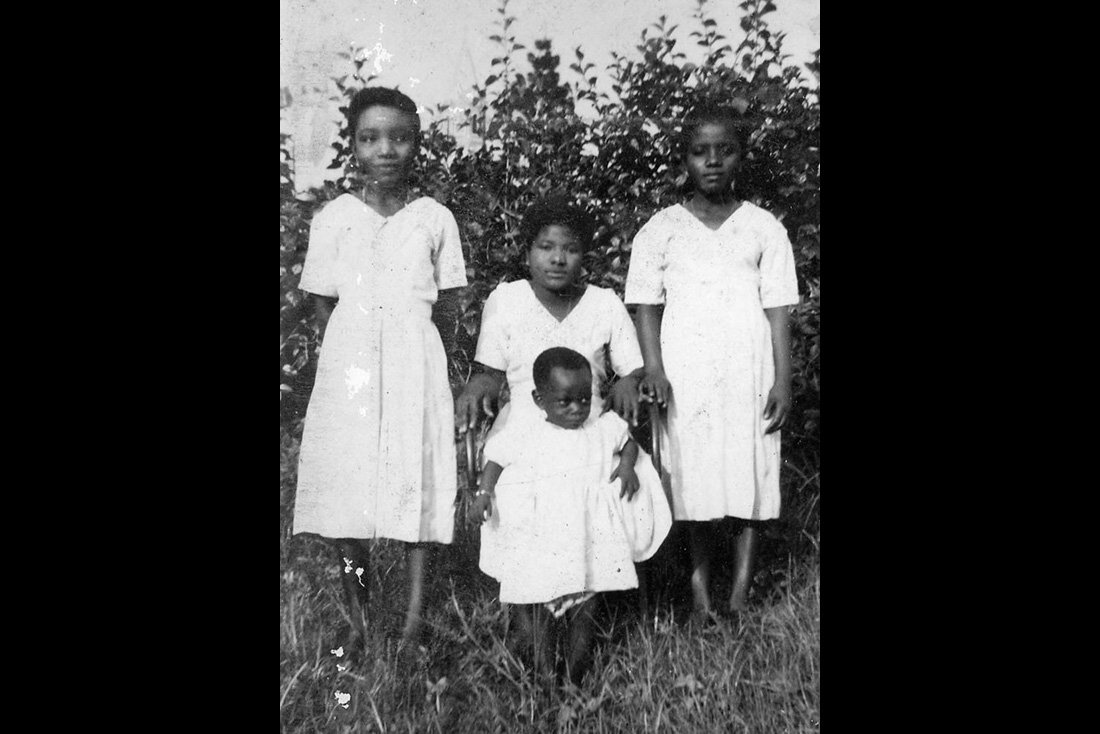

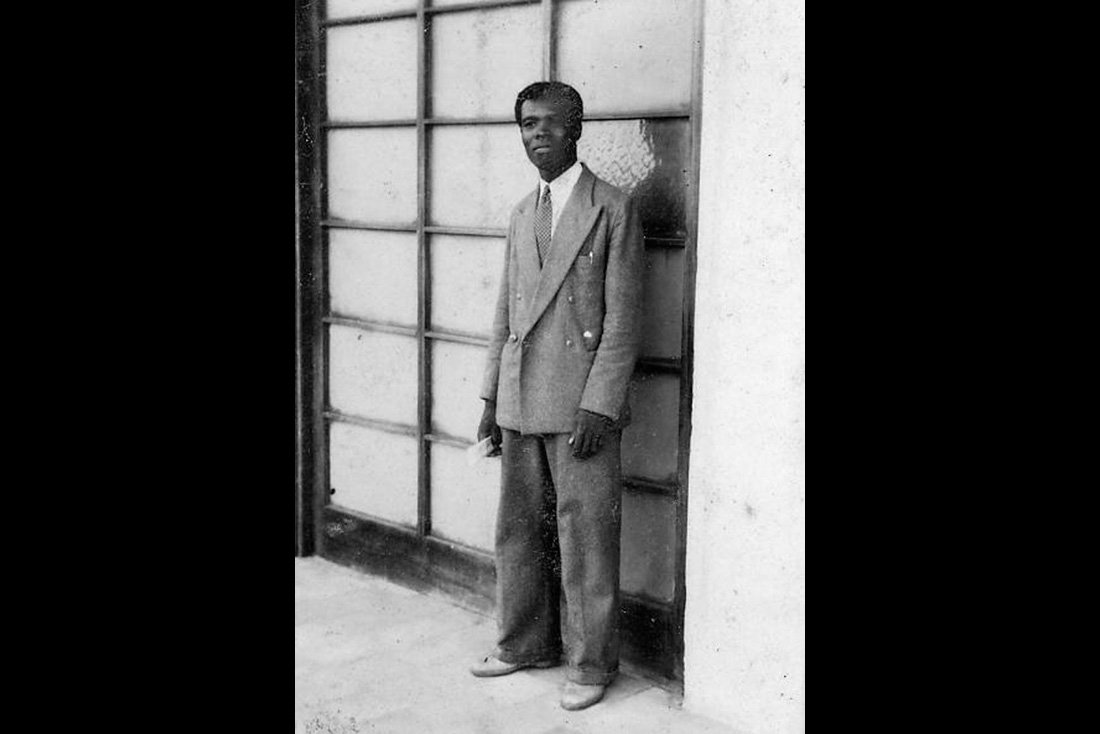

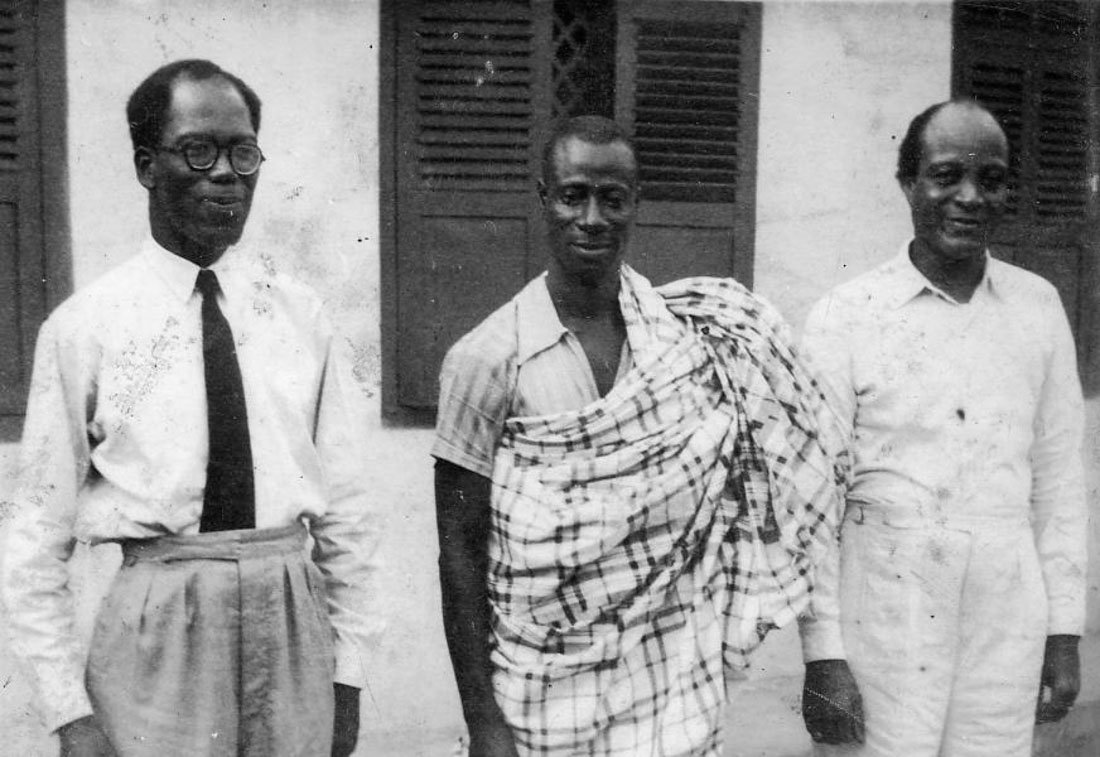

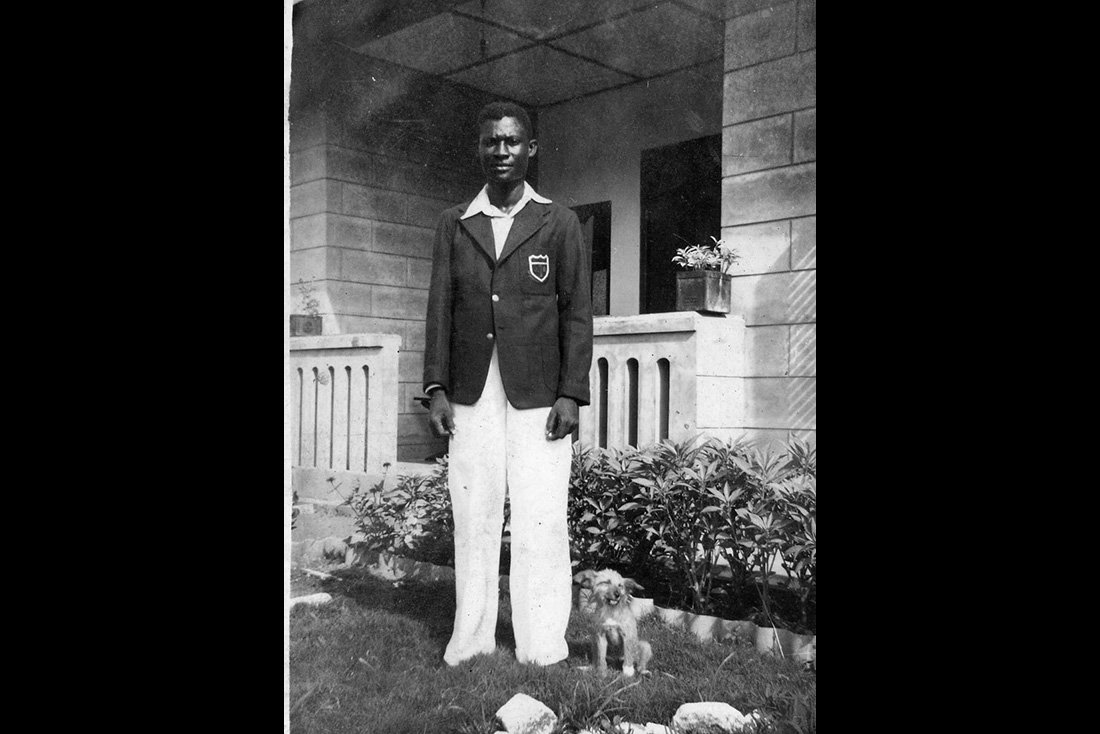

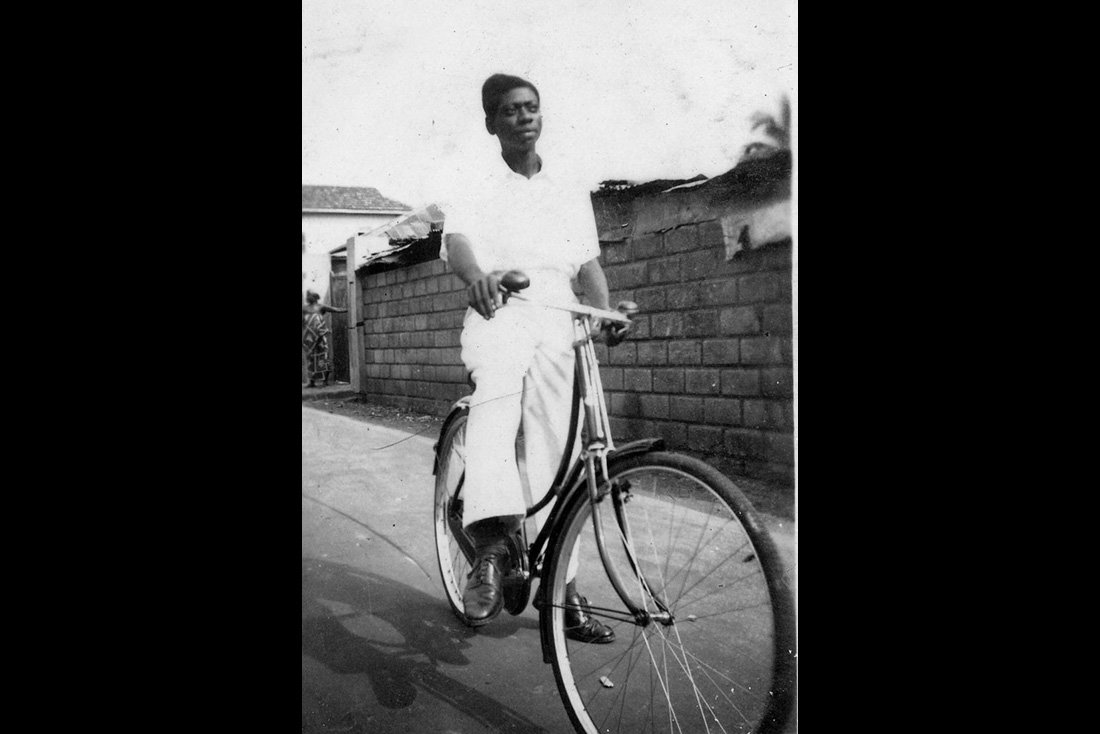

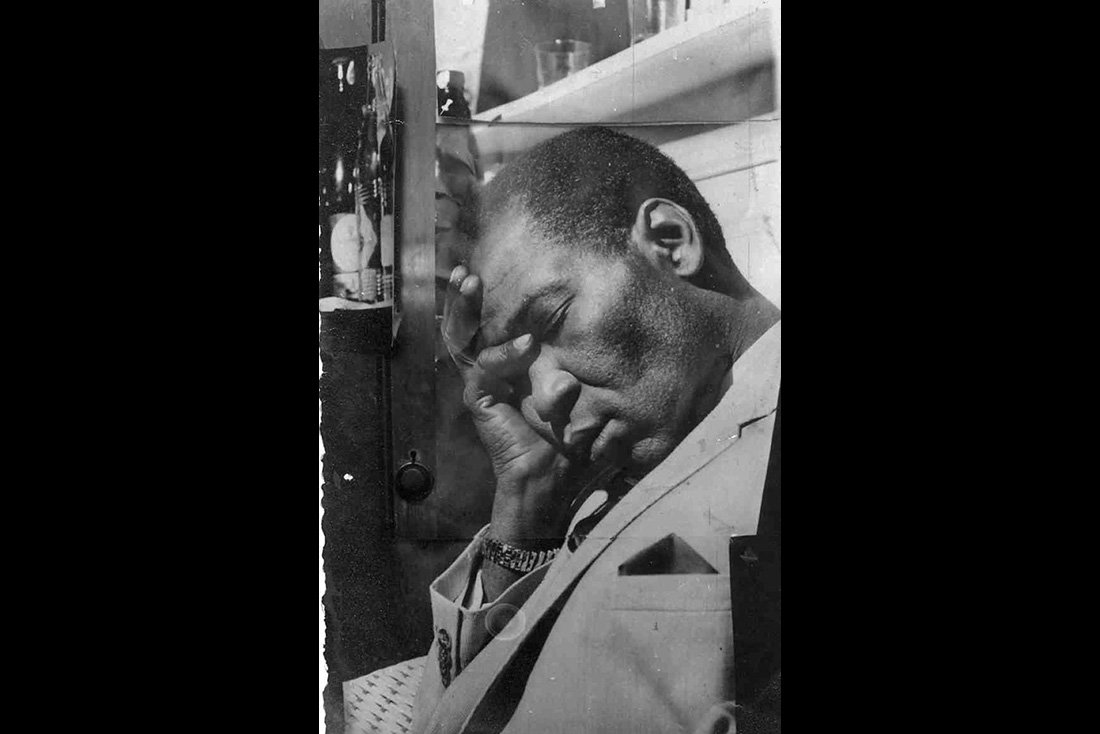

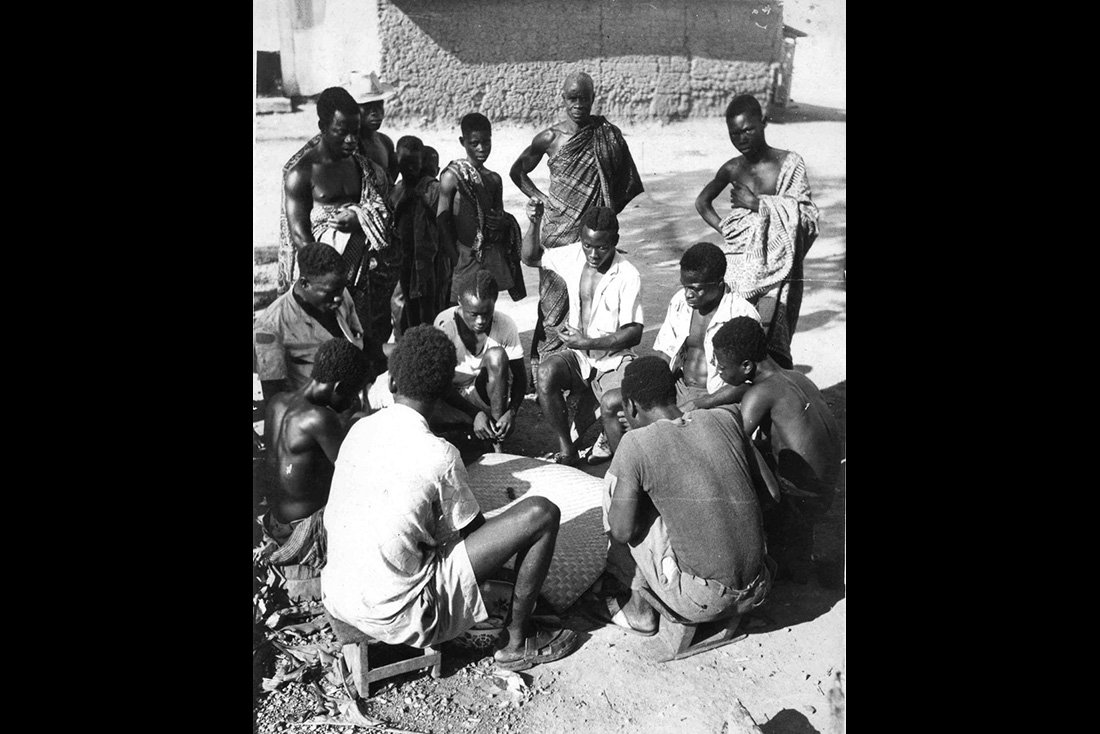

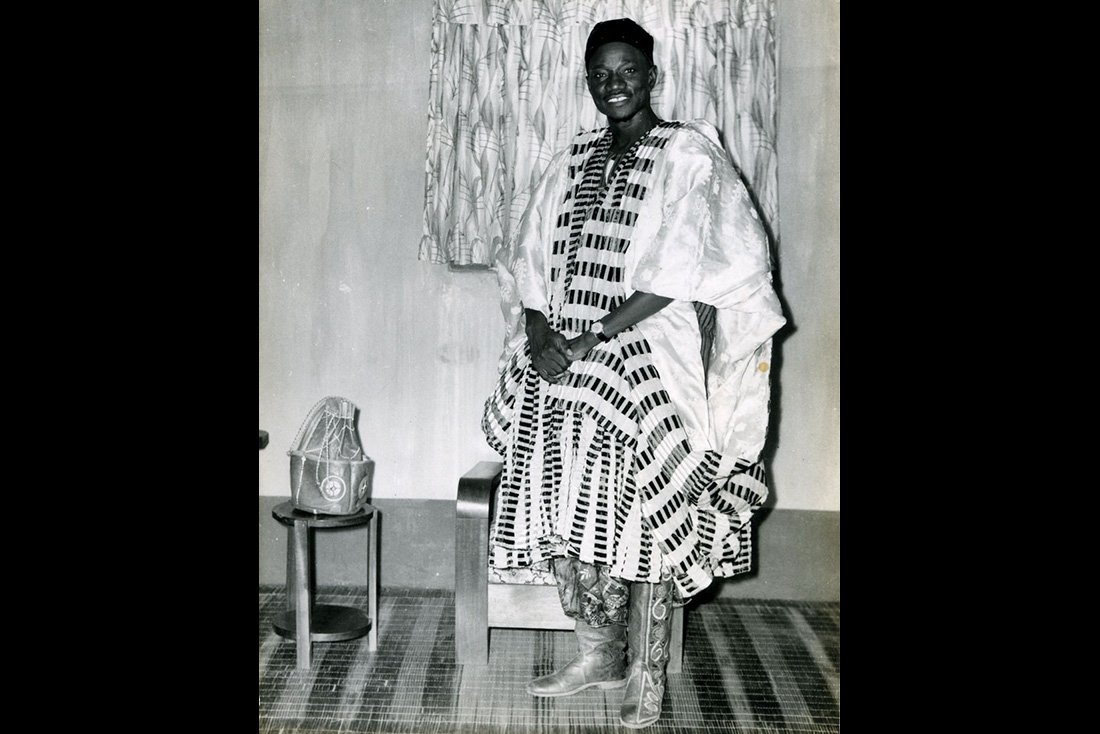

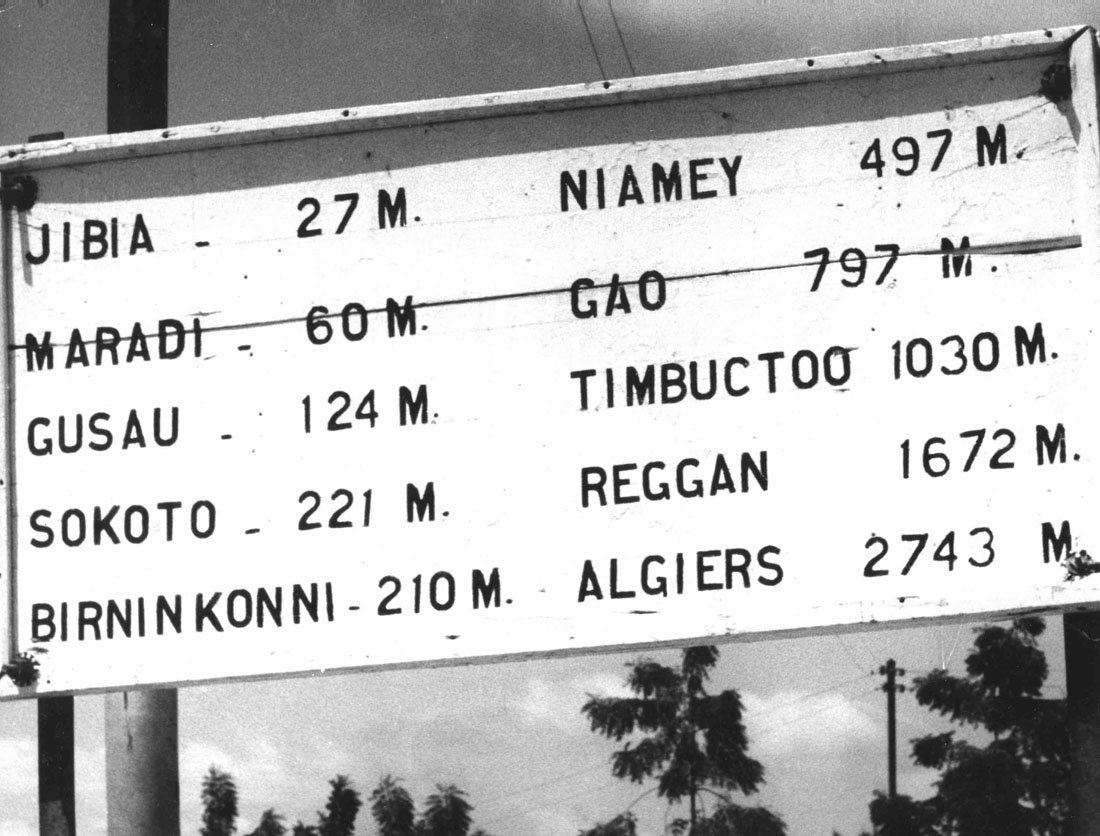

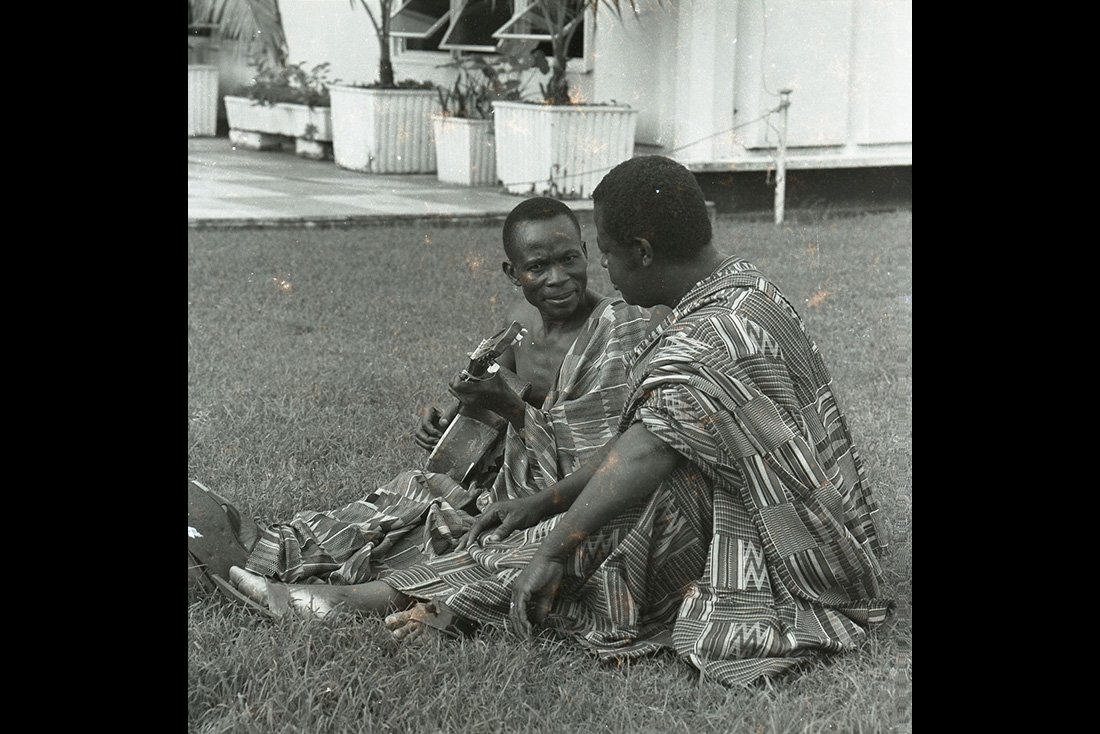

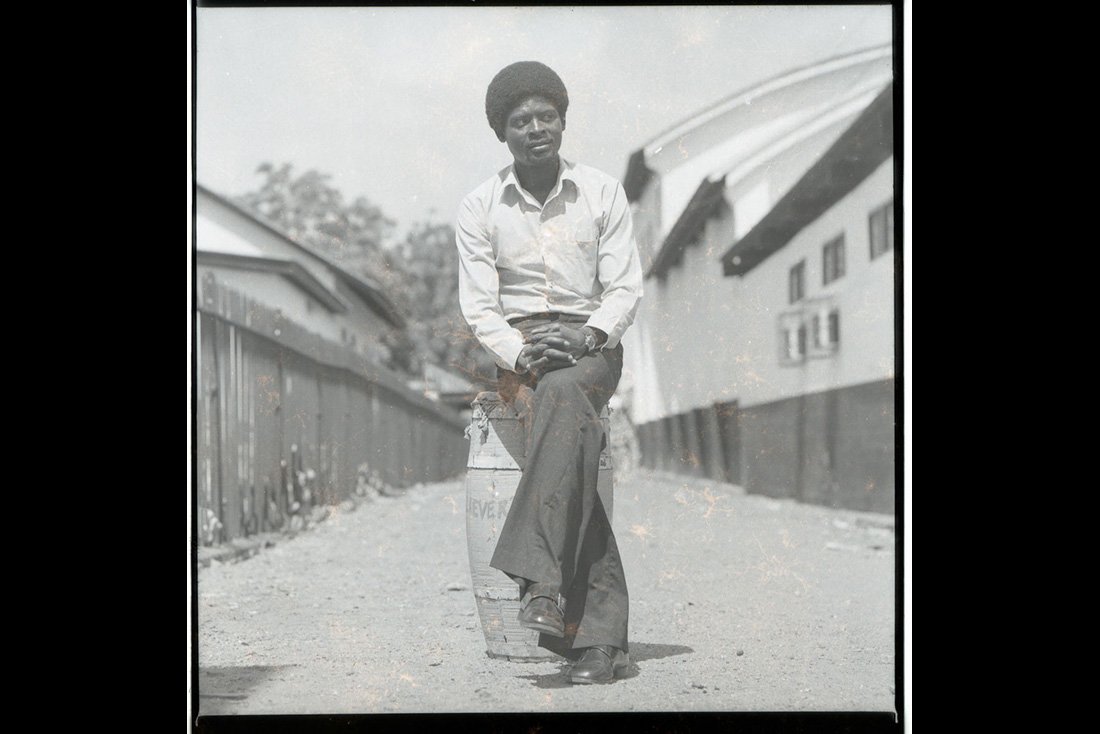

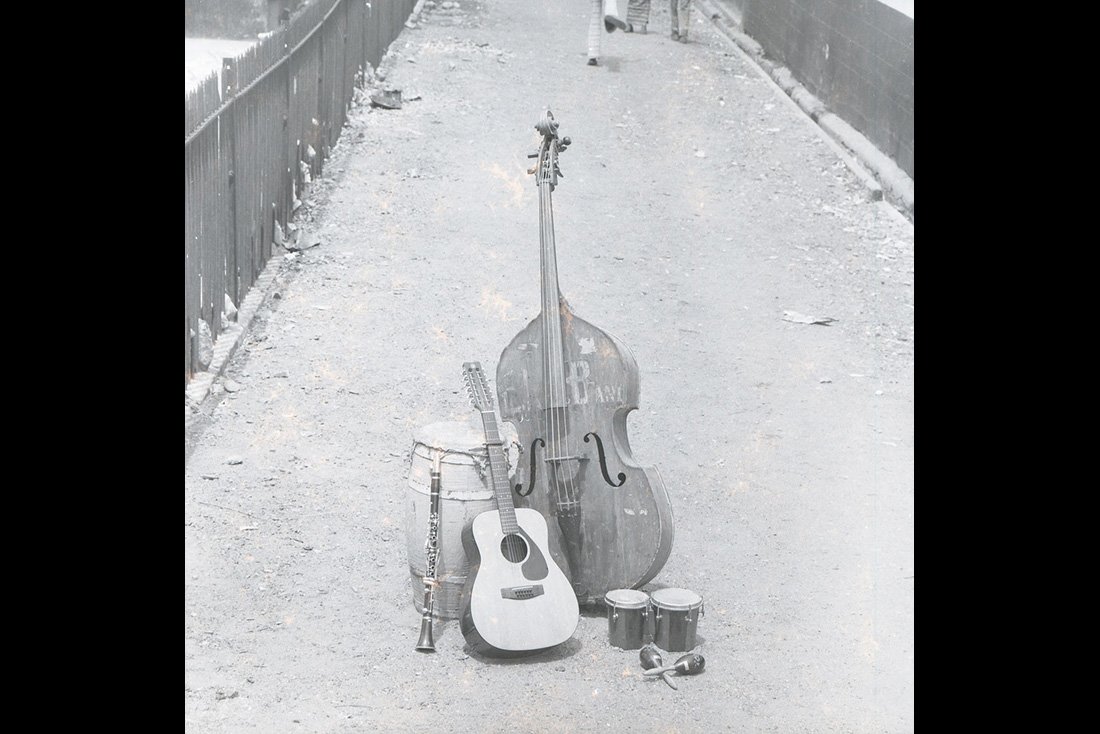

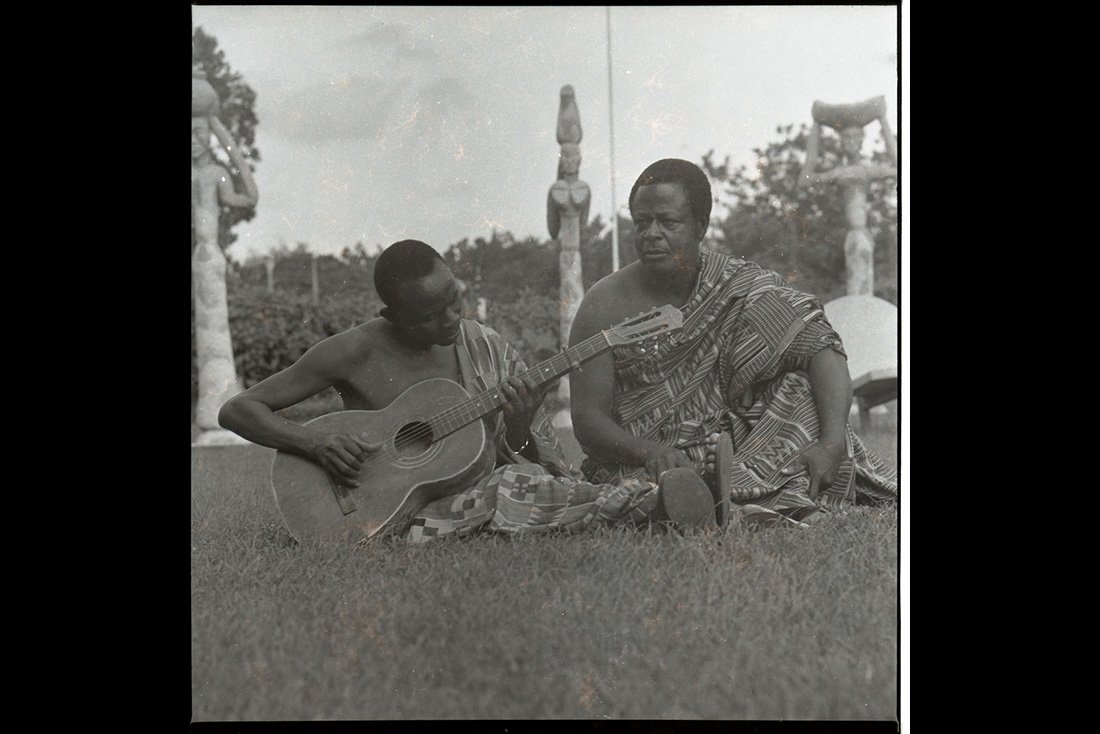

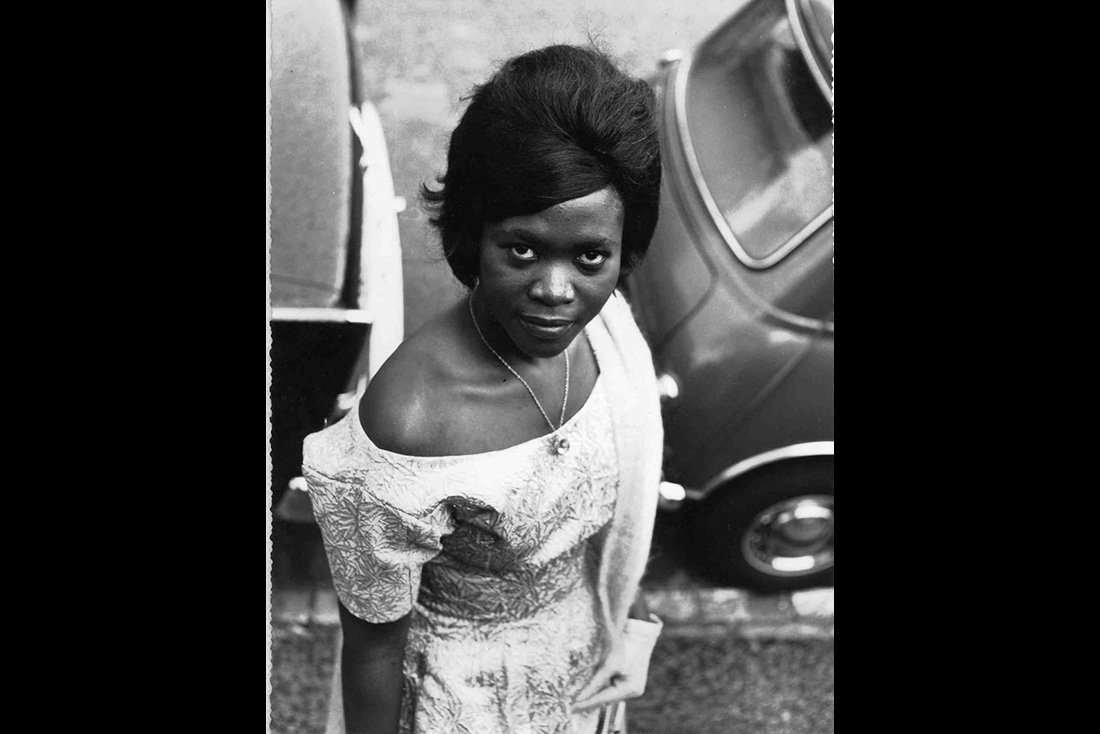

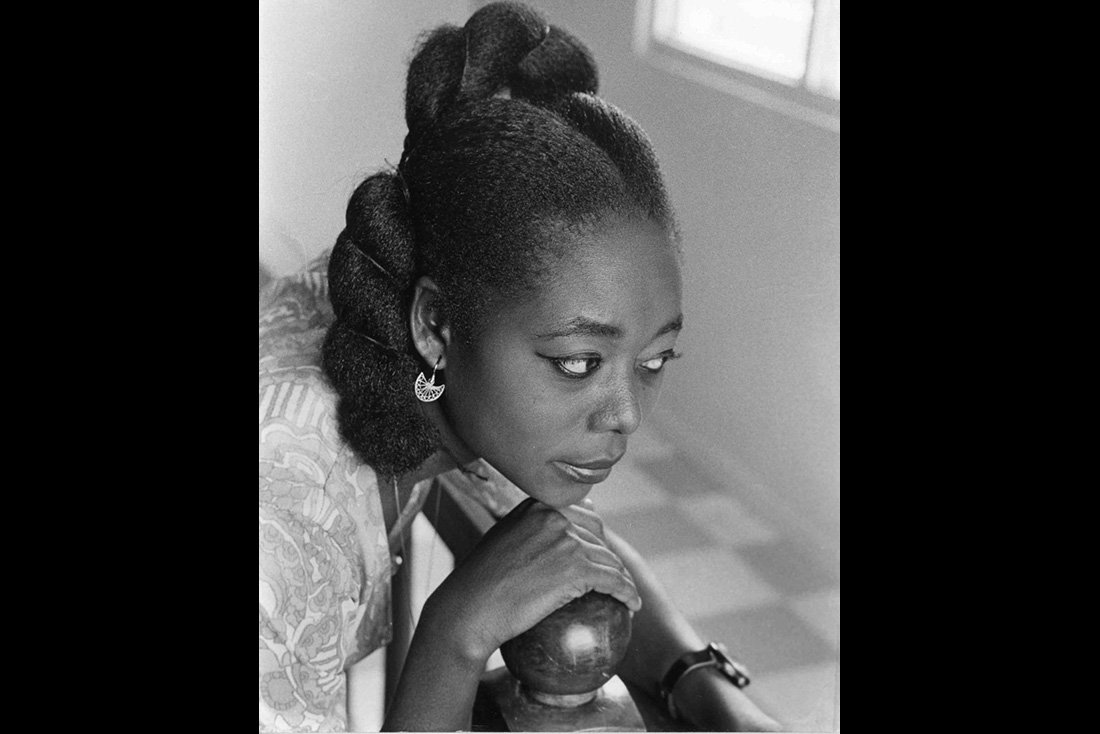

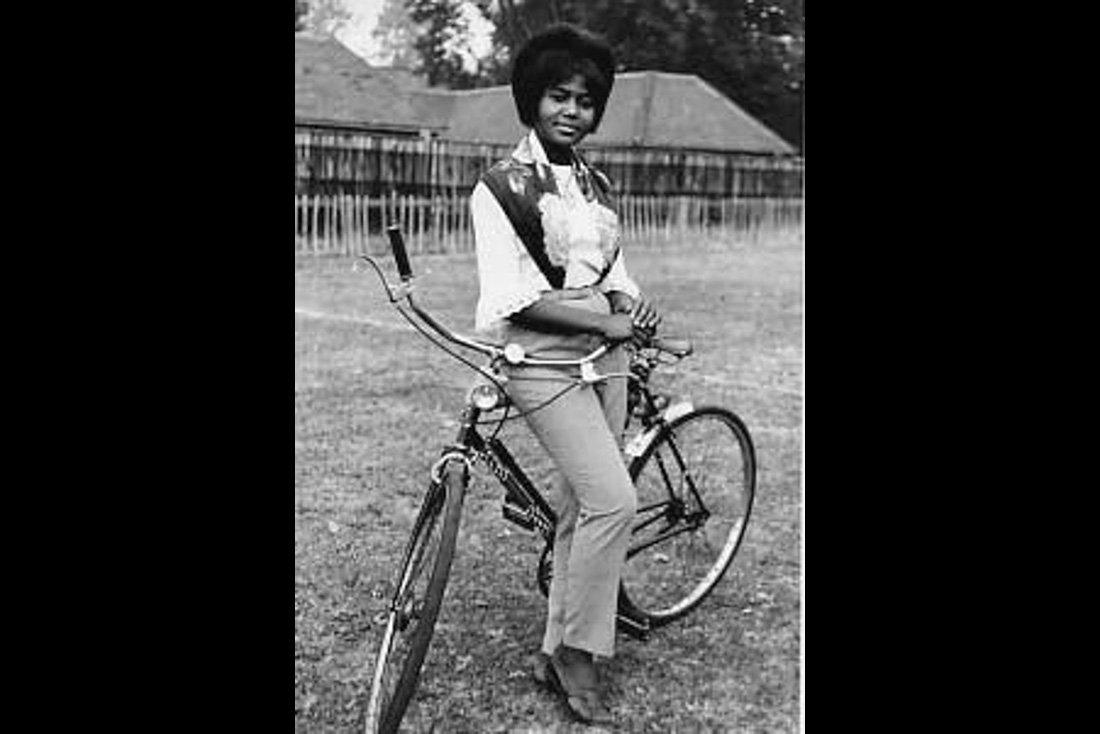

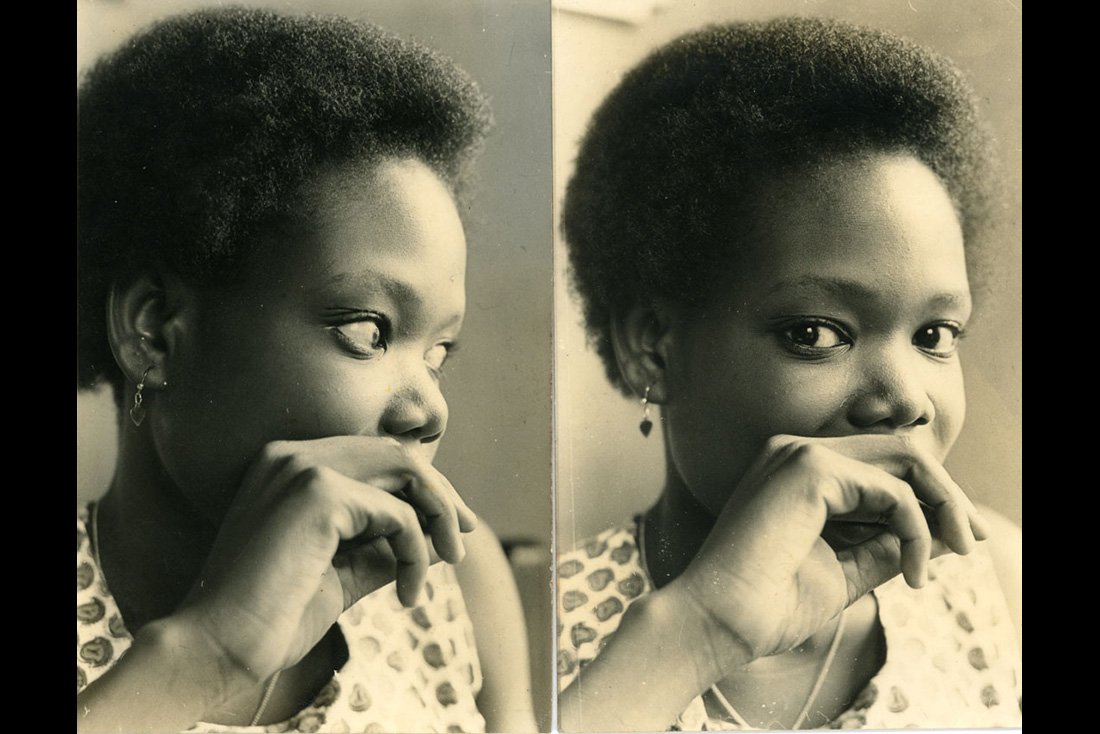

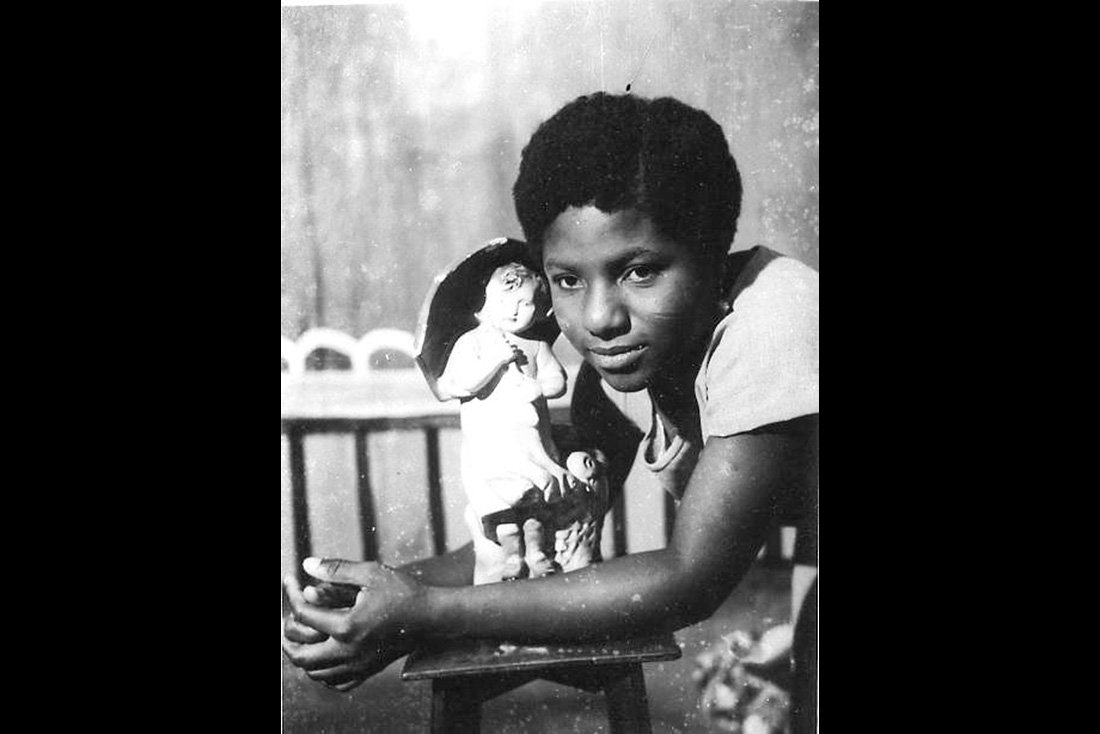

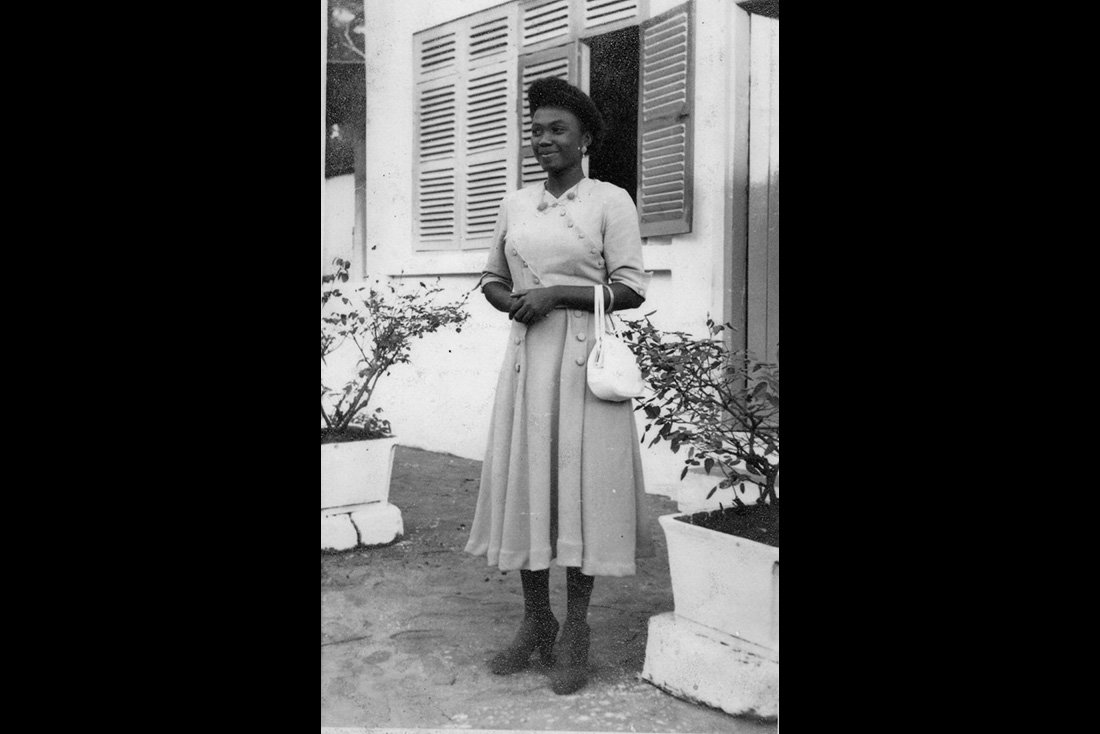

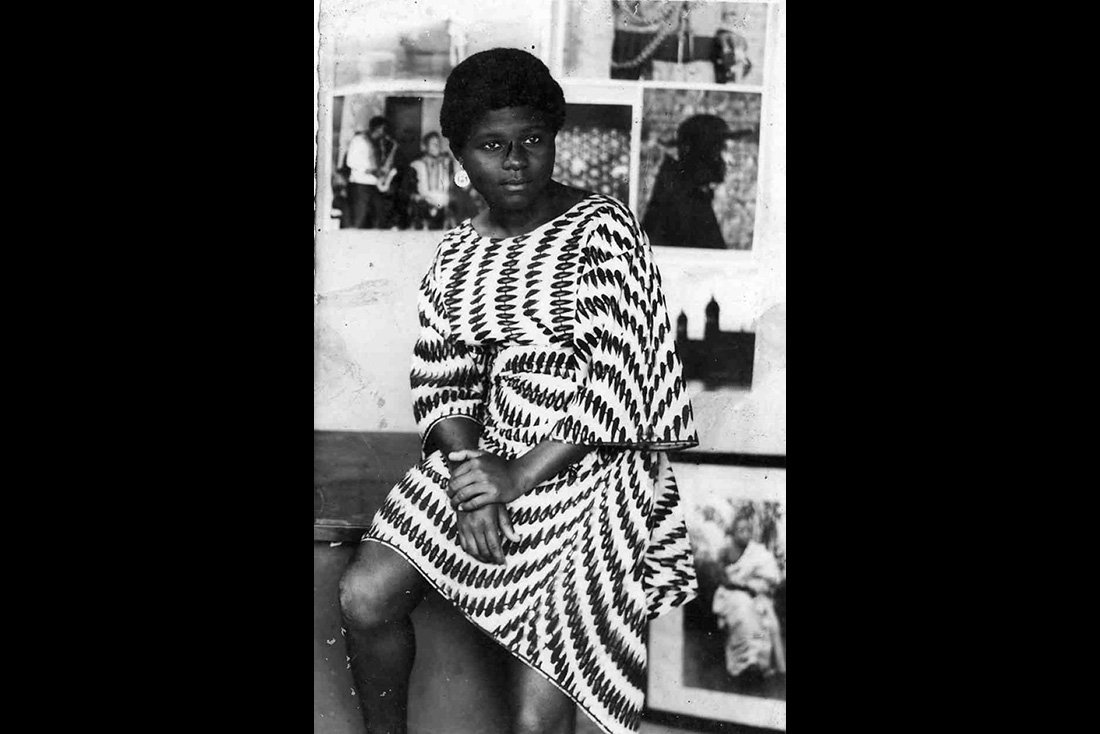

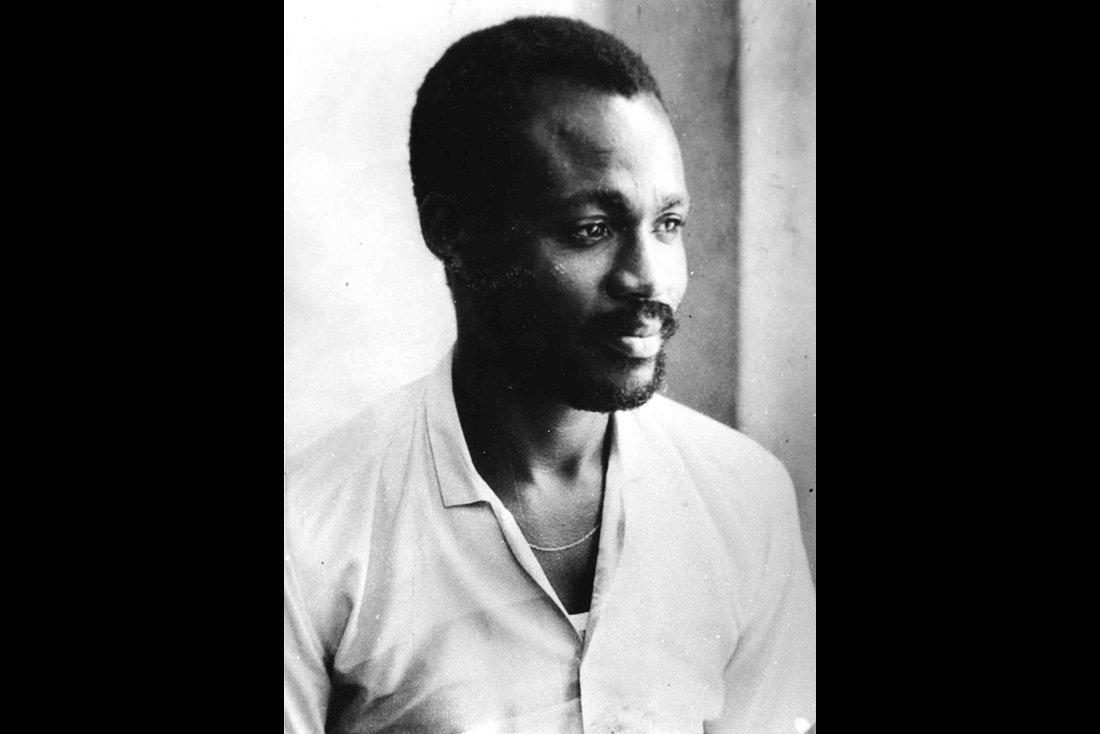

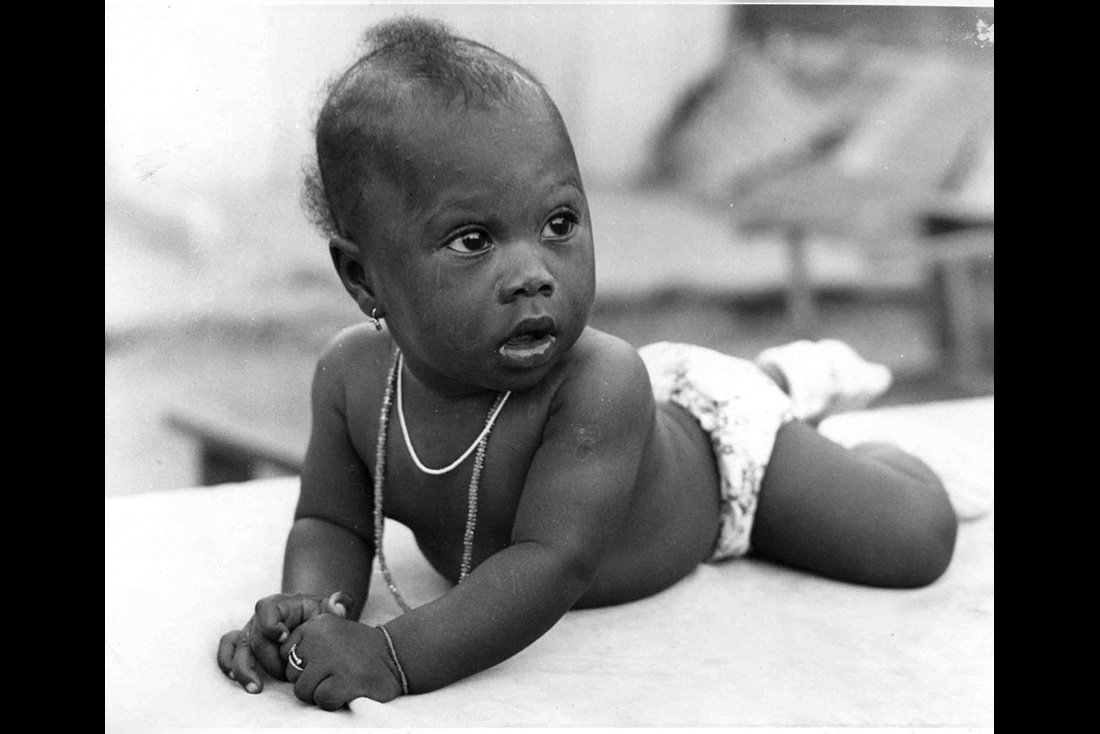

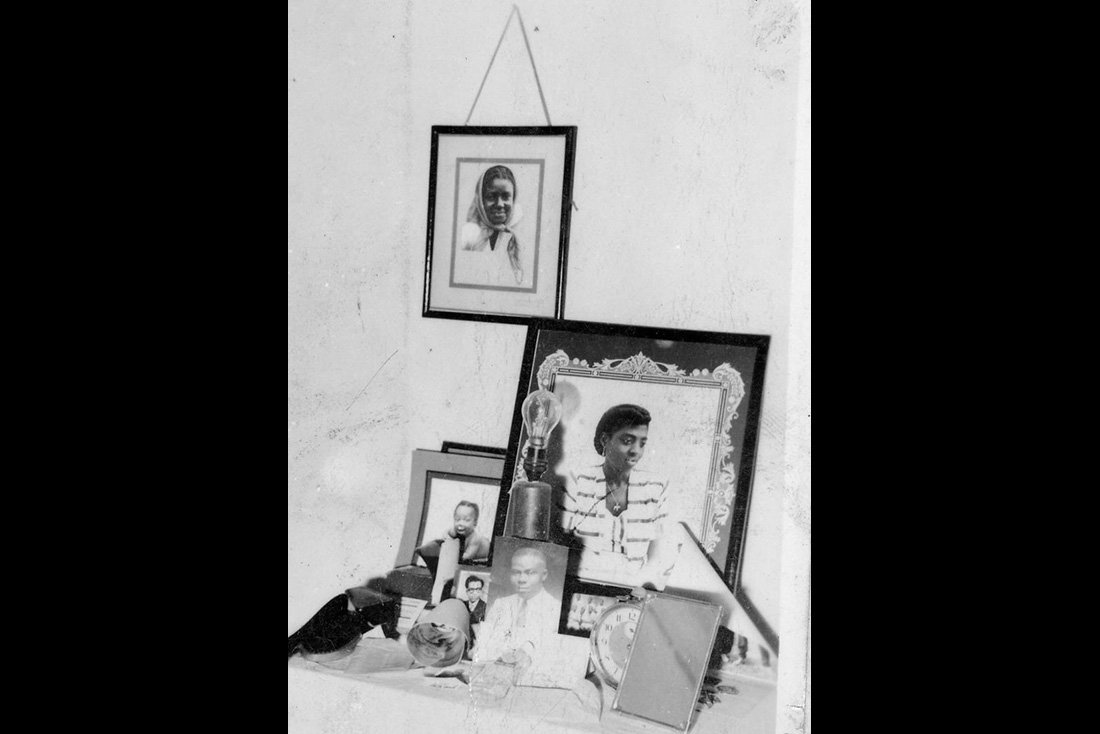

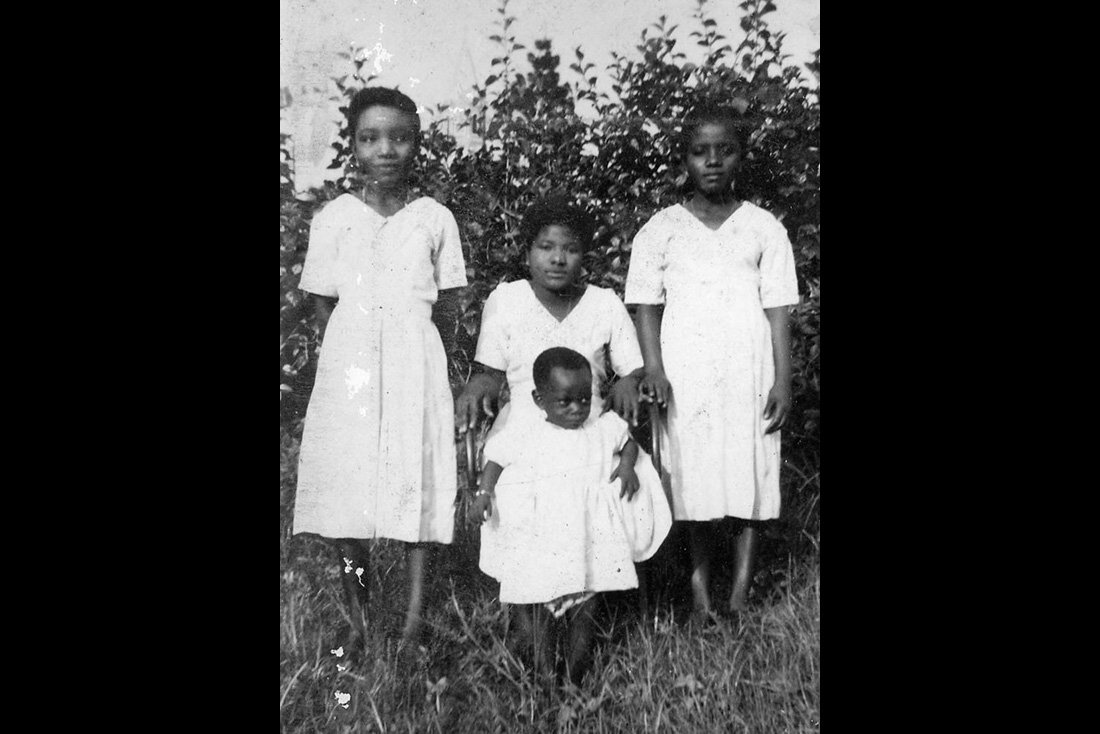

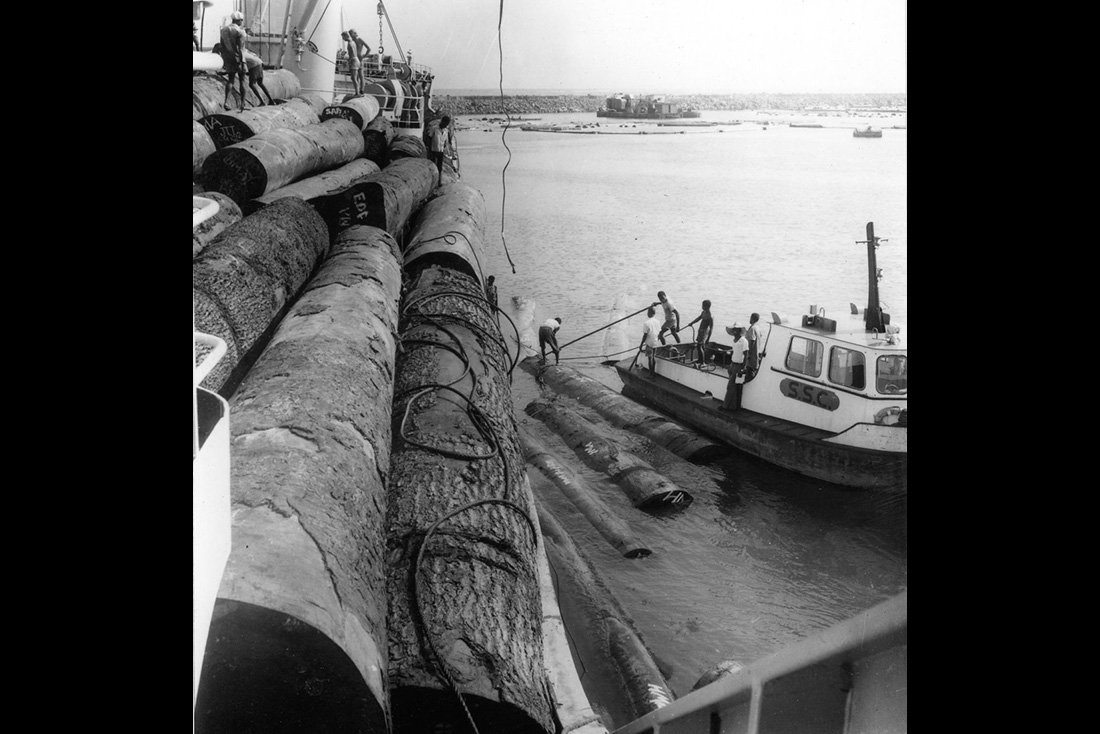

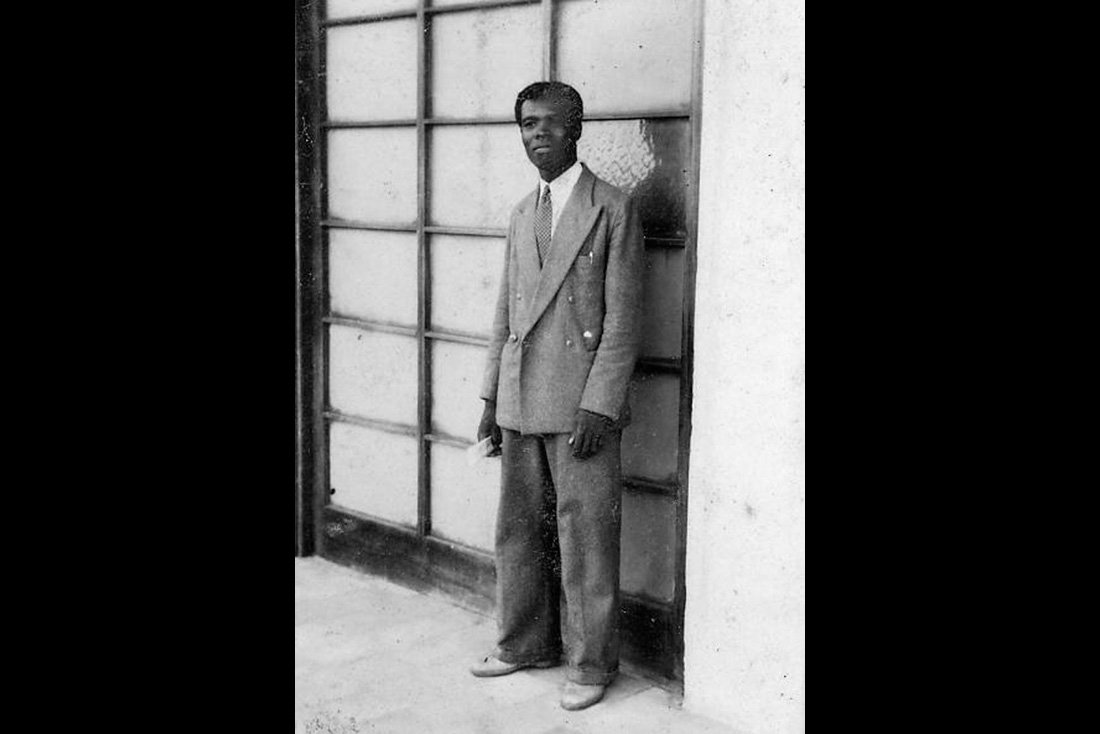

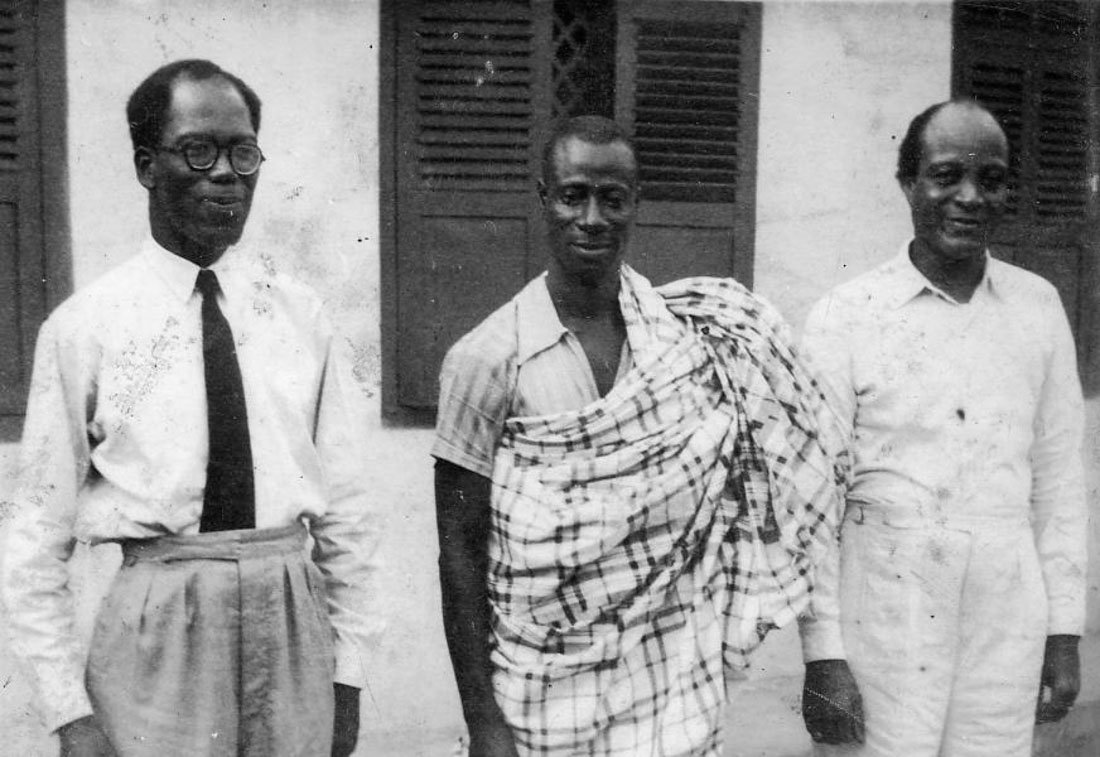

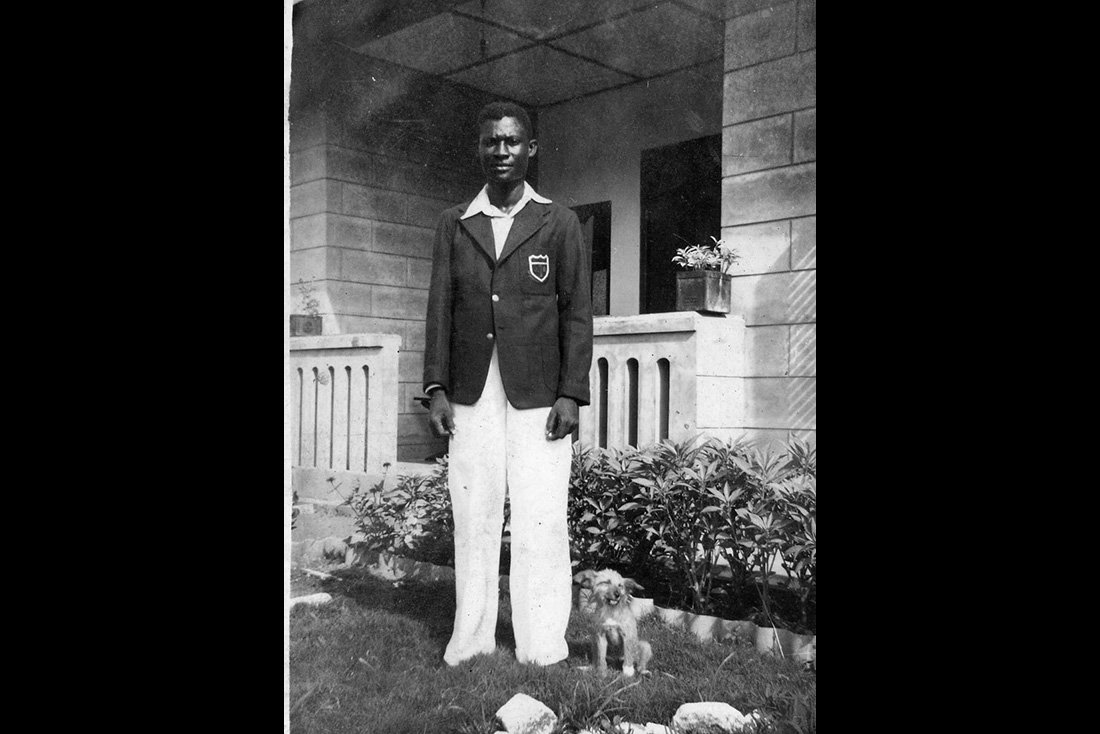

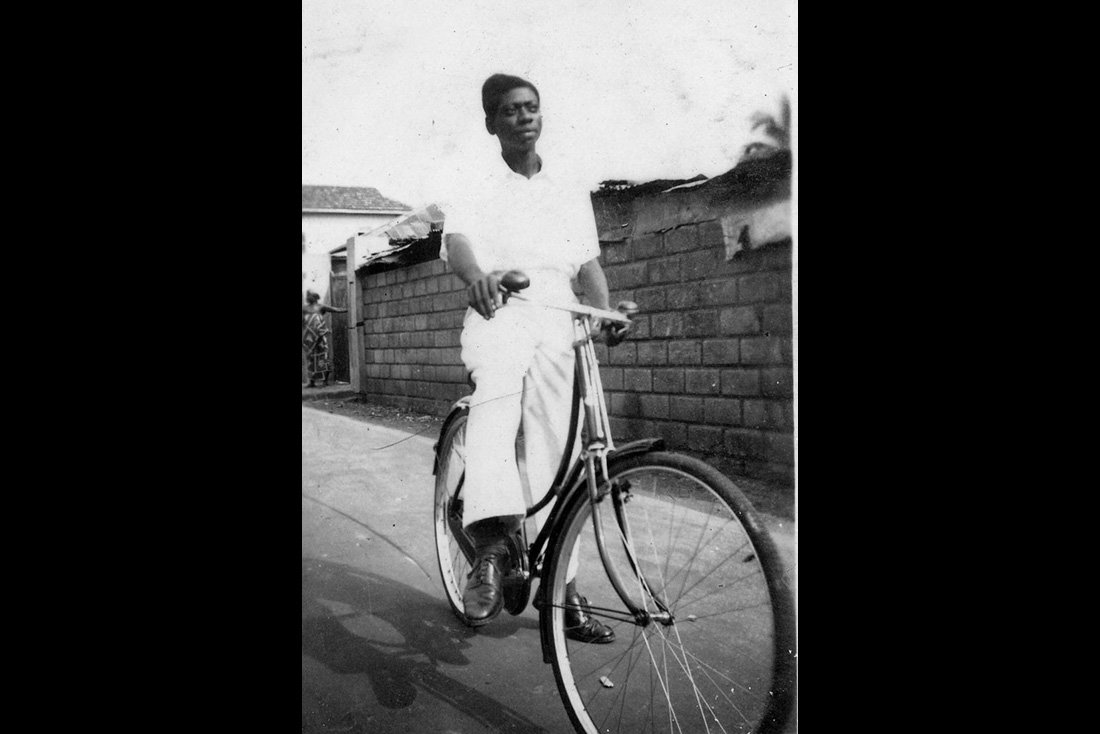

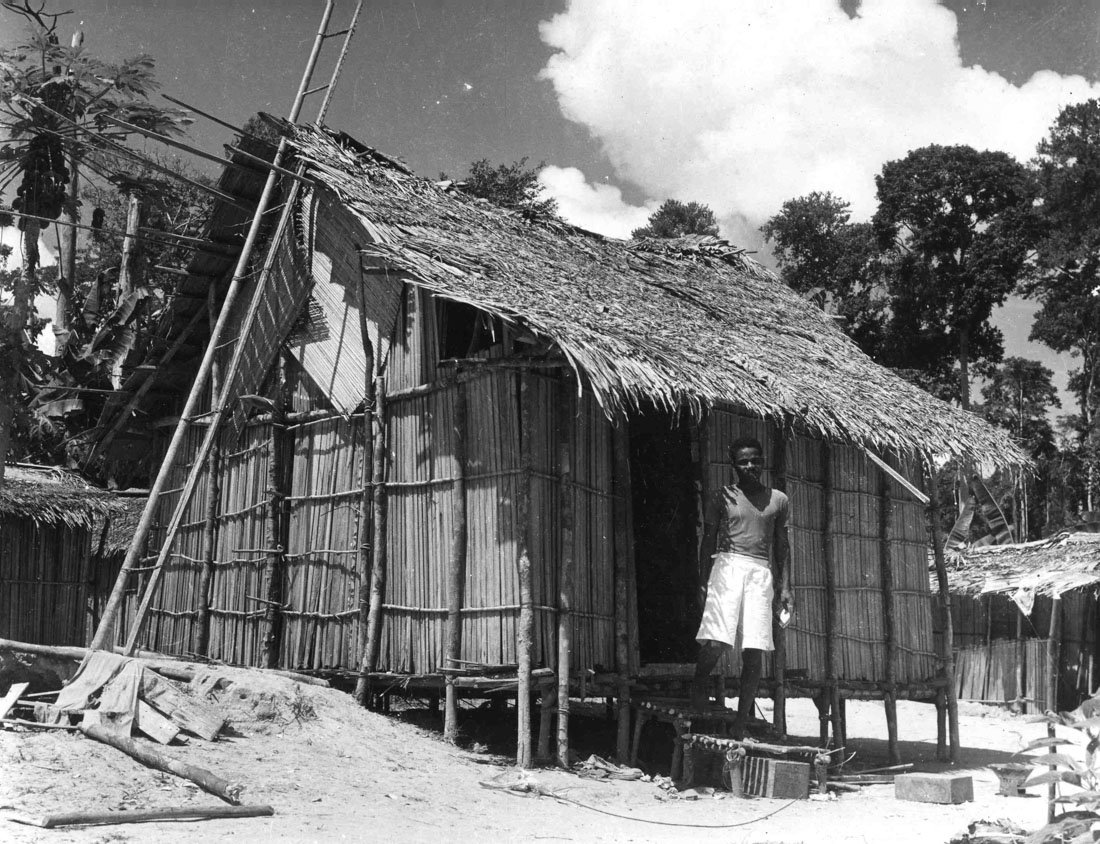

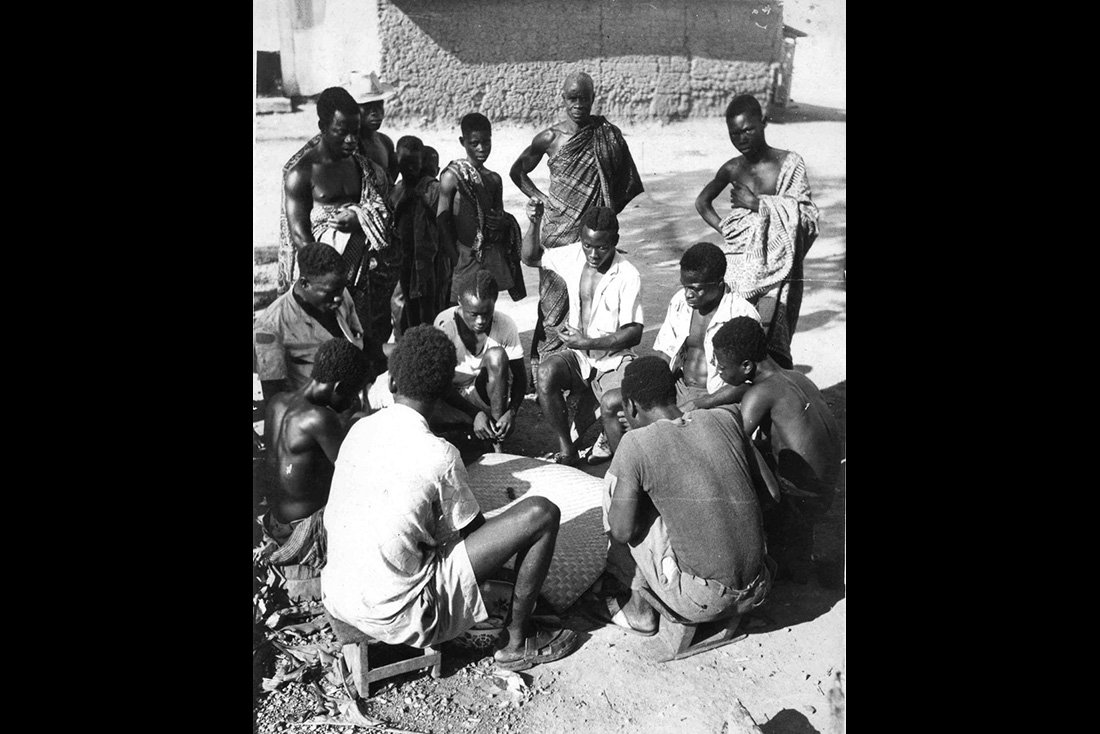

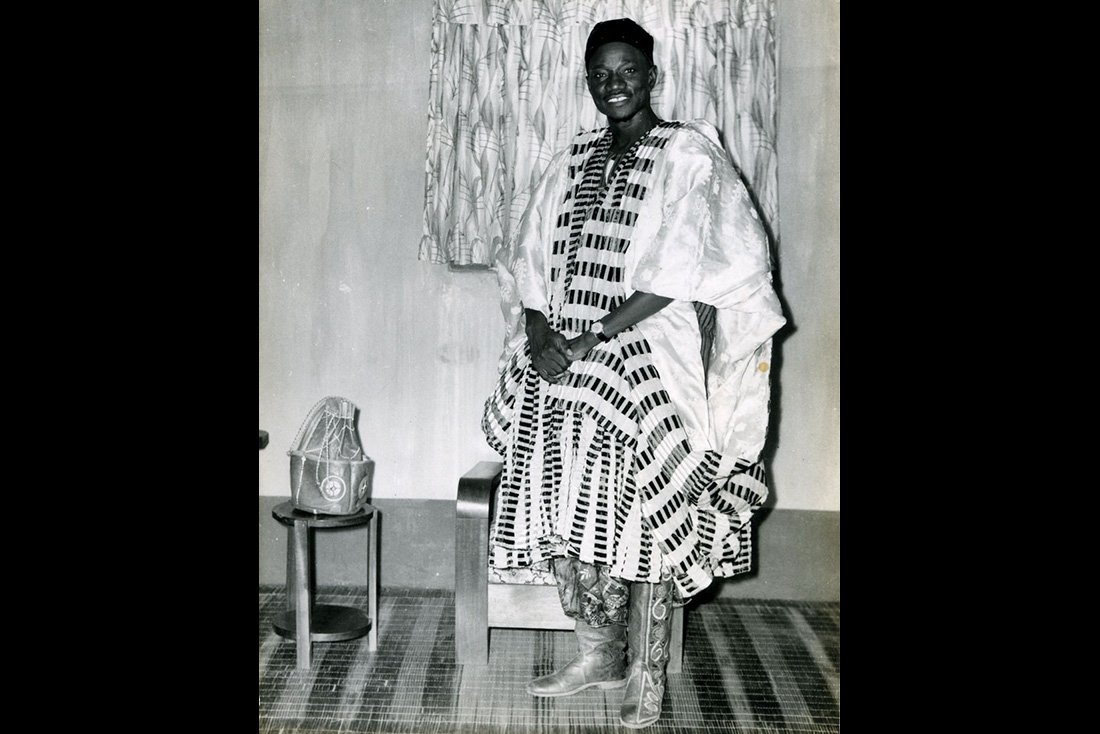

It was this history of modernity that we tried to tell in the exhibition and in the book we are creating together. It tells of the growth of a middle class that was giving local patronage to these photographers, civil servants, market traders, ball room dancing champions. It shows Accra growing from a conglomeration of fishing, farming and salt making villages into a town inhabited by traders of gold and ivory, new buildings and changing landscapes. It shows Ghana officially coming into being as an independent nation as power was handed over from the British to the legendary Nkrumah.

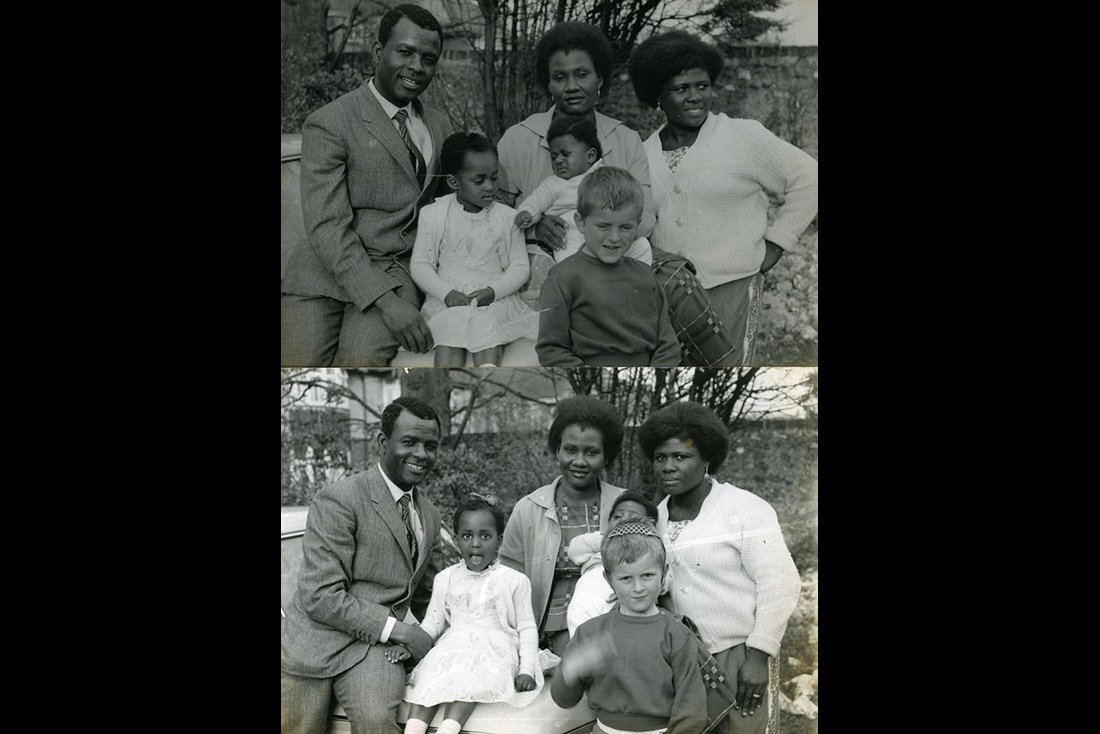

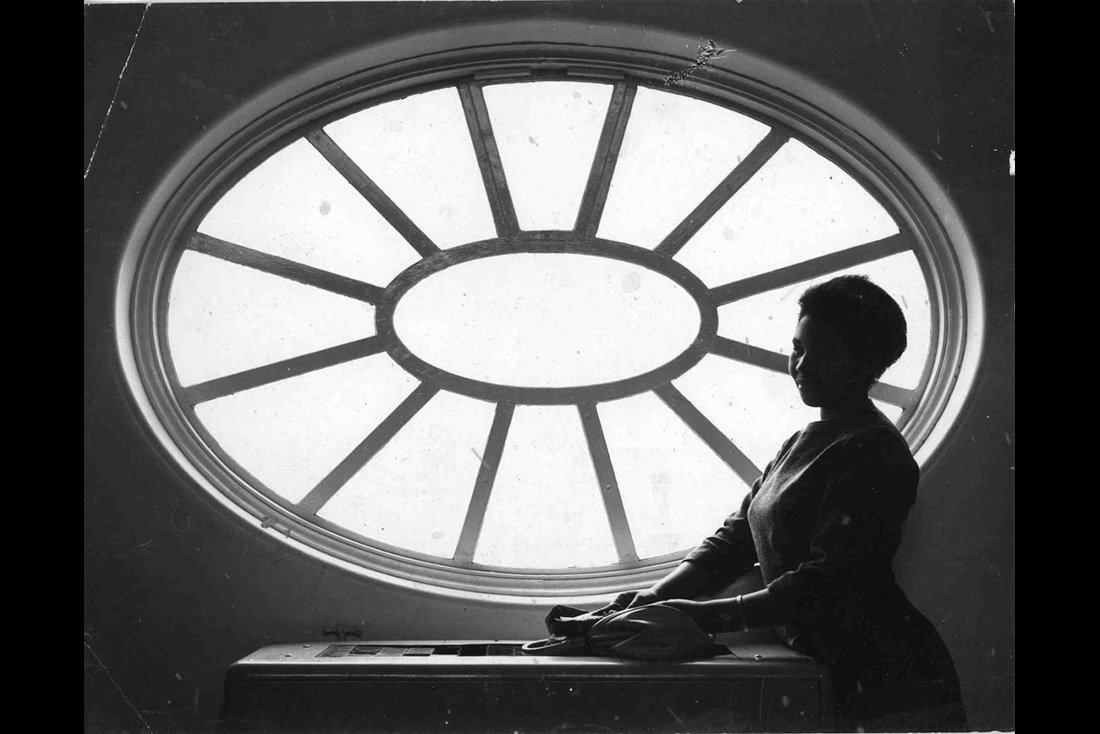

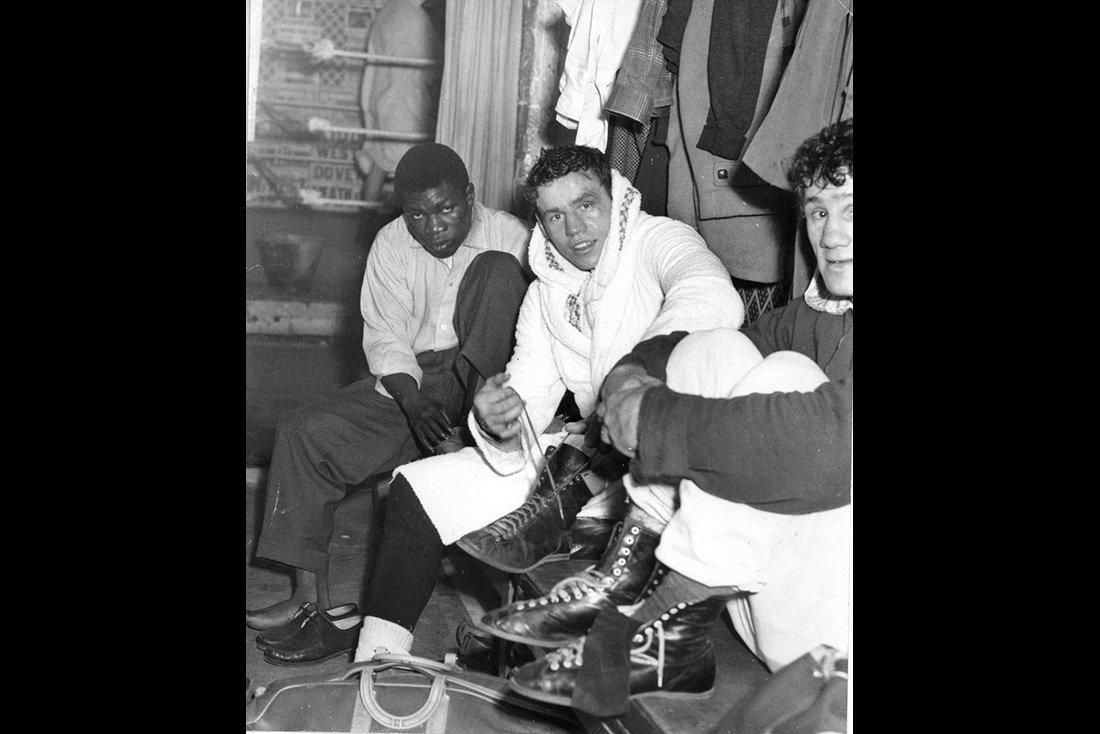

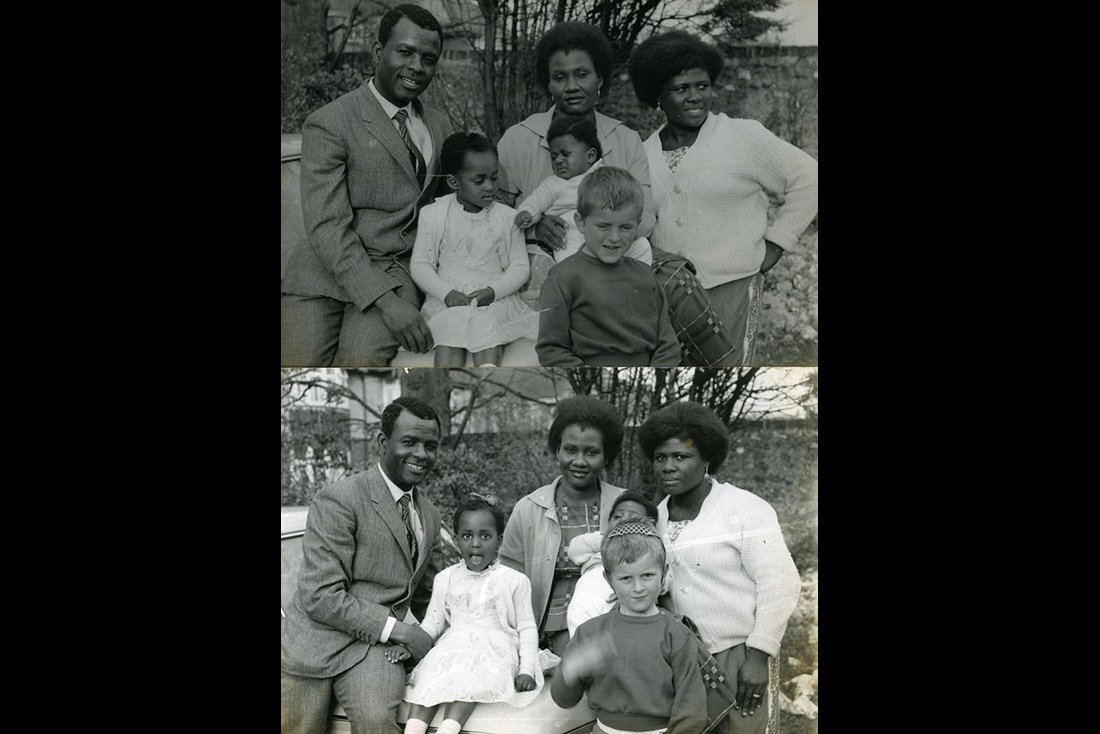

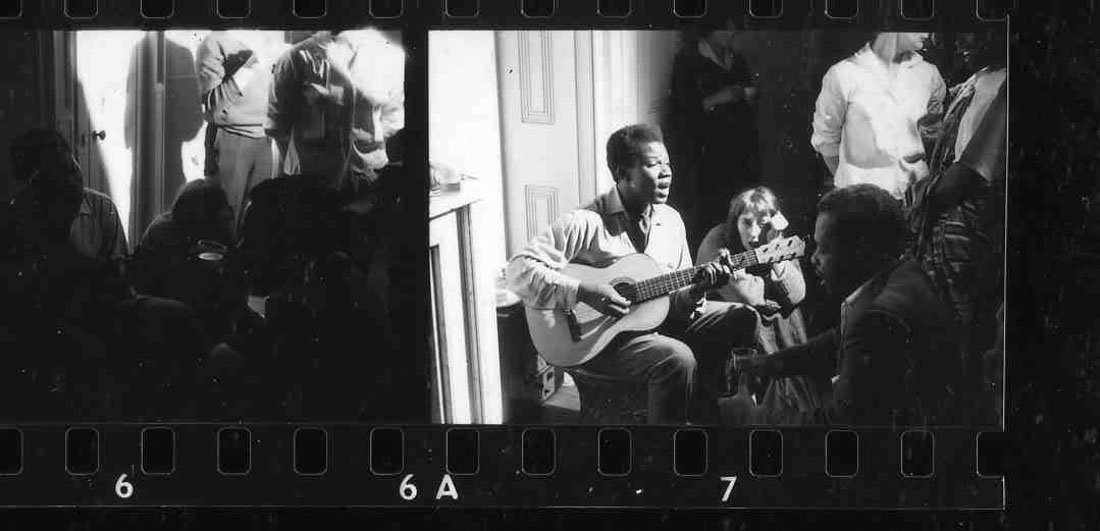

It shows the birth of a modern Diaspora as the economic and political situation in Ghana caused many to leave in search of education and work in the 1960s and 70s, and documents a history I’ve often seen in private family albums, but never elsewhere of young Africans integrated into their countries of choice.

ANO are involved in an ongoing process to digitise James Barnor’s photographs and to archive them in his old studio in Accra, which we hope to transform into a small museum of photography, as mentioned above to create a monograph of his work, and to somehow integrate the histories his photographs tell into the education or knowledge system of Ghana as a whole.