Living History

British Council, Accra, 2006

In Ghana, as in many other parts of Africa, history was passed on not as a static, written history, but as a living history, told through material culture. This notion of living history is brought alive in events known as ‘festivals’.

Through the re-enactments of historical events, such as migrations; through the objects, which tell the stories of former societies; through the horns and drums, which still today lament the passing of great rulers, we participate in a past, which becomes present and thus begins to inform our future. This exhibition looks at these events through the lenses of three contemporary Ghanaian photographers that each take a different approach to their subject and reveal different aspects of this living history.

For Samuel Arthur, also known as Big Sam Photos, pictures tell stories of what has happened in the past, he photographs in order to document the present for future prosperity. His past photography for royals, such as Okuapehene Oseadeayo Addo Dankwa III means that the demarcations of subject and object disappear in his portrayals of the Odwira of the Akuapem people, which is held to purify people of the past and strengthen them for future prosperity, peace and unity.

Images, such as that of Okuapehemaa Nana Dokua I, riding in her palanquin, are the ones we have come to associate with these events, but on another level, the images of the Okuapehene and of the Krontihene in mourning cloth reveal the solemn remembrance that also takes place. The symbolism of these events is made apparent by the hands of the Krontihene held in deference to the unseen Paramount, the Okuapehene and the fingers of the audience silently supporting and encouraging him in his eloquent dance. The drummers, who through drum language encode and preserve culture and thus history, are here calling people to gather, though at other times, they instrumentally relay the history of the state.

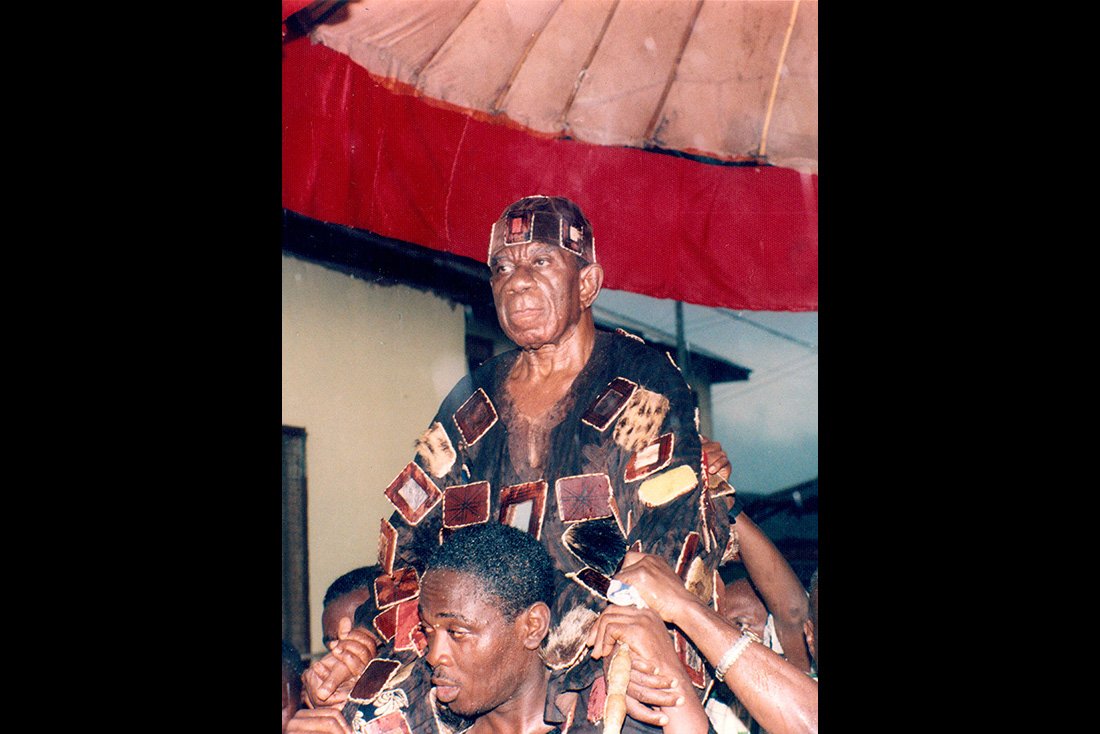

Photographer Nii Obodai examines the nature of cultural aesthetics in his work. He dreams of traveling universes, to which being an image-maker allows him to come closer. His poetic approach has been sought after in exhibitions in Accra, Bamako and Paris and reveals itself in these evocative black and white photographs of the Homowo of the Ga People, which recounts the migration of the Gas to present day. These pictures again reveal the system of encoding history in the drum and horn language, which has crossed over into the many cultures that make up Ghana today. They also capture the moment following libation, a form of recalling the deeds and legacies of forebears. Conversely, they are also a living testimony to the fluidity of history in these events. The ‘chief’ captured in these pictures is, according to the linguist of one of the major Ga stools, no chief at all, but the accruements of chieftaincy help him to recreate himself as such. History here as so often is the case is created in order to suit a certain trajectory and in time is passed on as ‘truth’.

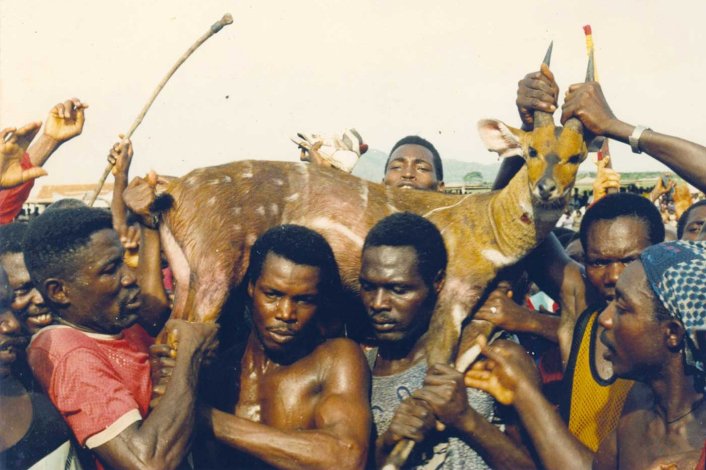

Thomas Fynn’s pictures, which aim at portraying Ghana’s rich culture, have resulted in a wide range of exhibitions throughout Ghana as well as internationally at events, in Germany, the Netherlands and Japan. His clear-sighted, objective and vivid approach to his subject is evident in these images of the Aboakyer, which is held yearly to renew the Effutus of Winneba. The woman seen here is dressed for the annual deer-hunting exercise, in which a deer is hunted for the rejuvenation of the people. This is done primarily by the Asafo Companies, such as the ones seen here in their company uniform, carrying flags, which depict events in the history of the company. The deer carried here is covered with medicine to alleviate its suffering and is paraded through the town, as part of the royal procession also pictured here.

The replacement of informal education systems with formal ones introduced by British colonialists has meant that our history is viewed through the lens of colonialism. This narrow view of our history, which divides it into pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial, denies it of the depth, context and complexity of the peoples that make up Ghana today.

In the past, history was passed on orally or in forms such as the drum language, an elaborate system of instrumentally encoding and preserving culture. Myths as well as stories of dynasties and migration were, and still are, recounted at events, known as ‘festivals’, which themselves form a kind of cultural text that can be decoded to reveal the histories of the people that partake in the event.

Like so many words that are remnants of colonial rule, such as ‘chief’, which does not begin to portray the many different layers and levels of the office it seeks to describe or ‘fetish’, which is still today used as a general term to denote anything to do with pre-colonial religions; the word ‘festival’ does little to convey the historical and often sacred significance of the events.

The survival of these events over time, like the institution known as chieftaincy, means that they remain relevant to a large part of the population. They are occasions on which people from the cities travel back to their hometowns or the towns of friends. Although the deeper meaning of the events, the literacy of texts, such as the drum texts, and the ideology embedded in them, have suffered a dramatic loss of value in contemporary Ghanaian society. In addition to this, many of the rites associated with these events are seen as clashing with modern religions, such as Christianity or Islam, though many manage to incorporate some of the cultural values of these events.

As cultural texts, they allow for a fluidity of history, in which participants are able to constantly recreate themselves as well as strengthen socio-political links within and across boundaries. And even though these events might seem as if they have remained static for centuries, they have often evolved with time, incorporating elements of Christianity or Islam and shedding rites that have proved anachronistic.

Historical commemorations often overlap with thanksgiving rites; in the Greater Accra Region, the Ga people celebrate Homowo, a harvest festival, which recounts the migration of the Gas to present day Accra, when according to Ga oral tradition, a severe famine broke out among the people, which inspired massive food production and eventually led to a successful harvest.

At other times, they are held to purify people of the past and strengthen them for future prosperity, peace and unity, such as the Odwira festival of the Akuapem or the Aboakyer of the Effutus.

This constant renewal of self through a reminder of the deeds and legacies of forebears and a cleansing of the past allows for a cyclical notion of time, in which the past and the present become one and thus, a living history.

Artists:

Sammy Arthur

Thomas Fynn

Nii Obodai